- Anatomical terminology

- Skeletal system

- Joints

- Muscles

- Heart

- Blood vessels

- Lymphatic system

- Nervous system

- Respiratory system

- Digestive system

- Urinary system

- Female reproductive system

- Male reproductive system

- Endocrine glands

- Eye

- Ear

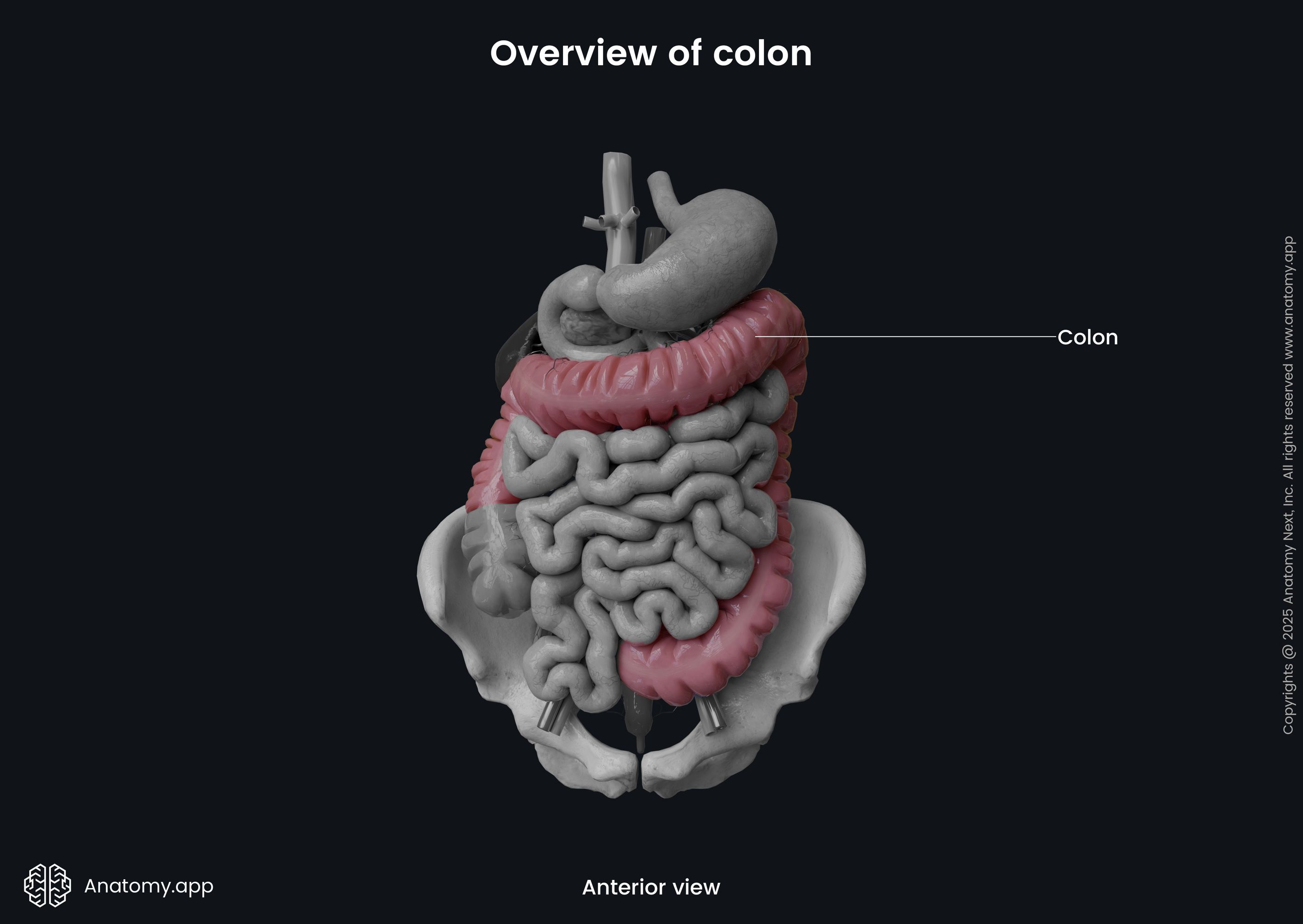

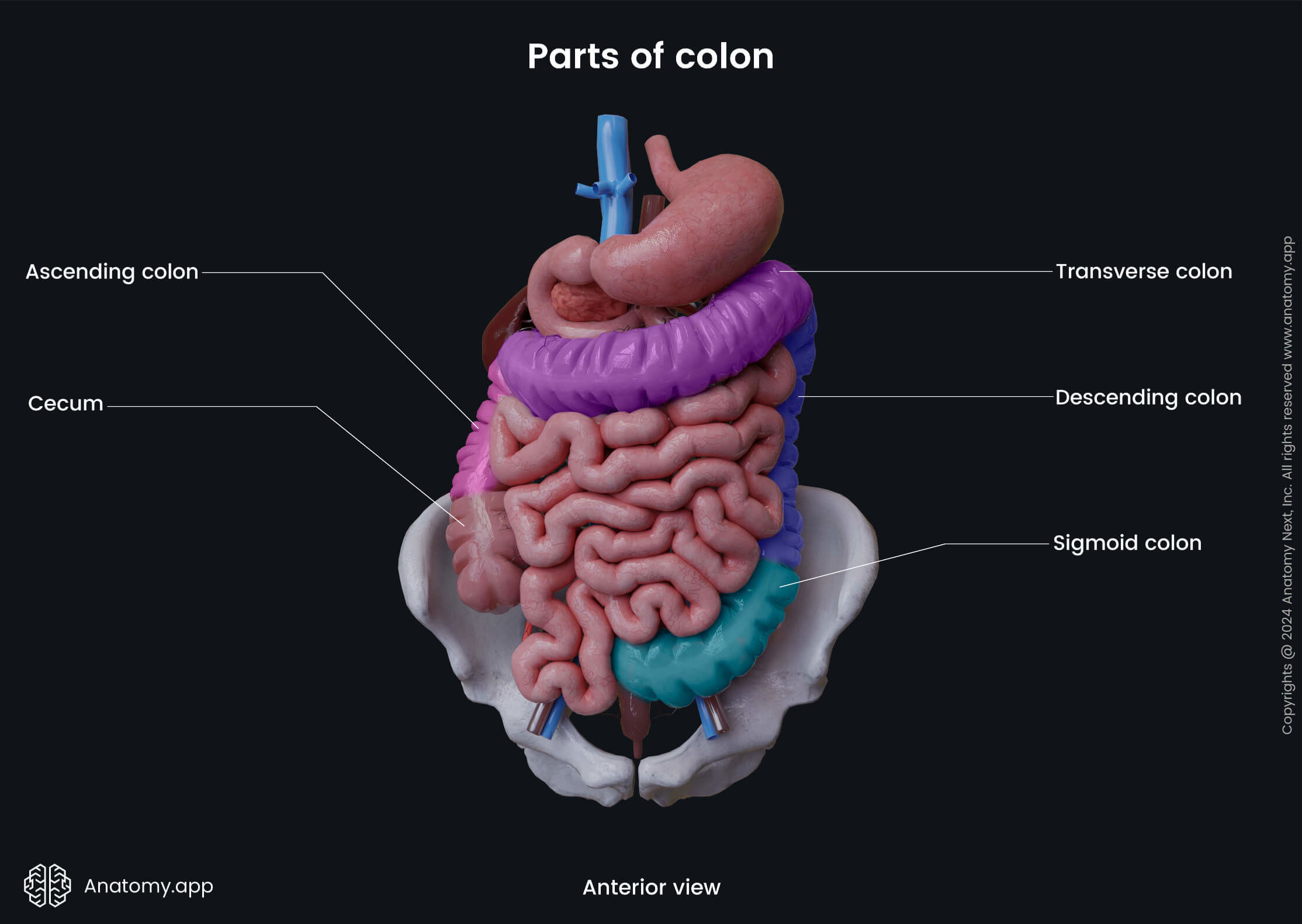

Colon

The colon (Latin: colon) is the longest part of the large intestine, and it connects the cecum to the rectum. It is approximately 5.9 feet (1.5 m) long in adults.

The colon is a continuation of the cecum, and it starts at the level of the ileocecal junction, where the ileocecal valve is located. The colon ends by transforming into the rectum at the rectosigmoid junction, which projects at the level of the third sacral vertebra (S3). The colon is composed of four parts:

- Ascending colon

- Transverse colon

- Descending colon

- Sigmoid colon

The ascending colon and descending colon lie retroperitoneally (behind the peritoneum), but the transverse colon and the sigmoid colon - intraperitoneally (within the peritoneum).

Characteristics of colon

Like other parts of the large intestine, the colon also presents several typical characteristics:

- Larger diameter and fixed position compared to the small intestine;

- Taeniae coli - three narrow longitudinal bands, formed by the outer muscular layer of the wall of the colon; their contractions produce the haustra;

- Haustra - small segmented pouches created by sacculation of the colon; the haustra give a segmented appearance to the colon, and they are formed by the contractions of the longitudinal muscles found within the taeniae;

- Epiploic appendices (omental appendices, appendices epiploicae) - small fat-filled projections of the peritoneum located on the outer surface of the colon along the free and omental taeniae; they are found more commonly in the distal parts of the colon, particularly on the surface of the sigmoid colon.

Three teniae can be distinguished:

- Mesocolic taeniae - located posteromedially; correspond to the attachment of the mesentery; the transverse mesocolon and sigmoid mesocolon attach to them;

- Omental taeniae - located posterolaterally and serve for the attachment of the greater omentum;

- Free taeniae - located on the anterior side of the intestine and are not attached to any anatomical structure.

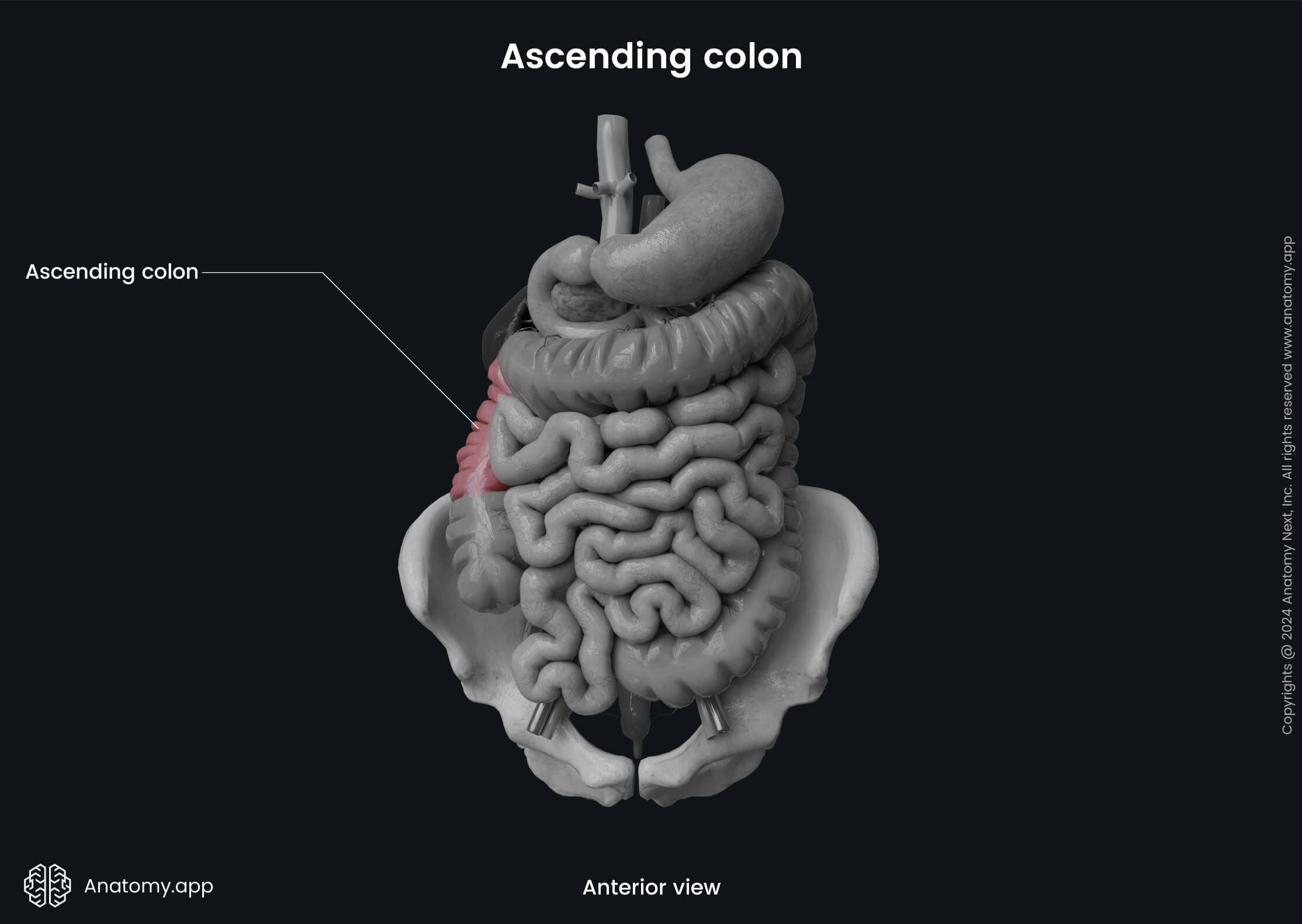

Ascending colon

The ascending colon is the first part of the colon, and it is around 6 to 8 inches (15 - 20 cm) in length. It is a retroperitoneal organ, as it is not covered by the peritoneum from all sides but only from the anterior and lateral aspects. The ascending colon starts at the level of the ileocecal junction and extends upward on the right side of the abdominal cavity towards the right lobe of the liver. Upon reaching the liver, the ascending colon makes a sharp turn to the left side and forms the right colic flexure (also called the hepatic flexure). The right colic flexure marks the junction between the ascending colon and the transverse colon.

Posterior to the right colic flexure lies the inferior aspect of the right kidney. The posterior aspect of the right colic flexure is not covered by the peritoneum. Therefore, it is in direct contact with the renal fascia. The right lobe of the liver is located superiorly, the fundus of the gallbladder lies anteromedially, and the descending part of the duodenum is situated medially to the right colic flexure.

There are two deep vertical recesses called paracolic gutters that lie on both sides of the abdominal cavity. The right paracolic gutter is located between the lateral surface of the ascending colon and the lateral abdominal wall. Similarly, on the left side, between the lateral aspect of the descending colon and the lateral abdominal wall, lies the left paracolic gutter. These vertical recesses are basically free interconnected abdominal cavity spaces.

Ascending colon relations

As mentioned before, the anterior and lateral surfaces of the ascending colon are covered by the peritoneum. The posterior surface, on the other hand, attaches to the retroperitoneum through a layer of connective tissue called Toldt’s fascia. Posterior to the ascending colon lie the following structures:

- Iliac fascia

- Quadratus lumborum muscle

- Iliolumbar ligament

- Transversus abdominis muscle

- Renal fascia

The anterior surface of the quadratus lumborum muscle is crossed by several important neurovascular structures. Therefore, they are also located posterior to the ascending colon, and they include the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, ilioinguinal nerve, iliohypogastric nerve and fourth lumbar artery.

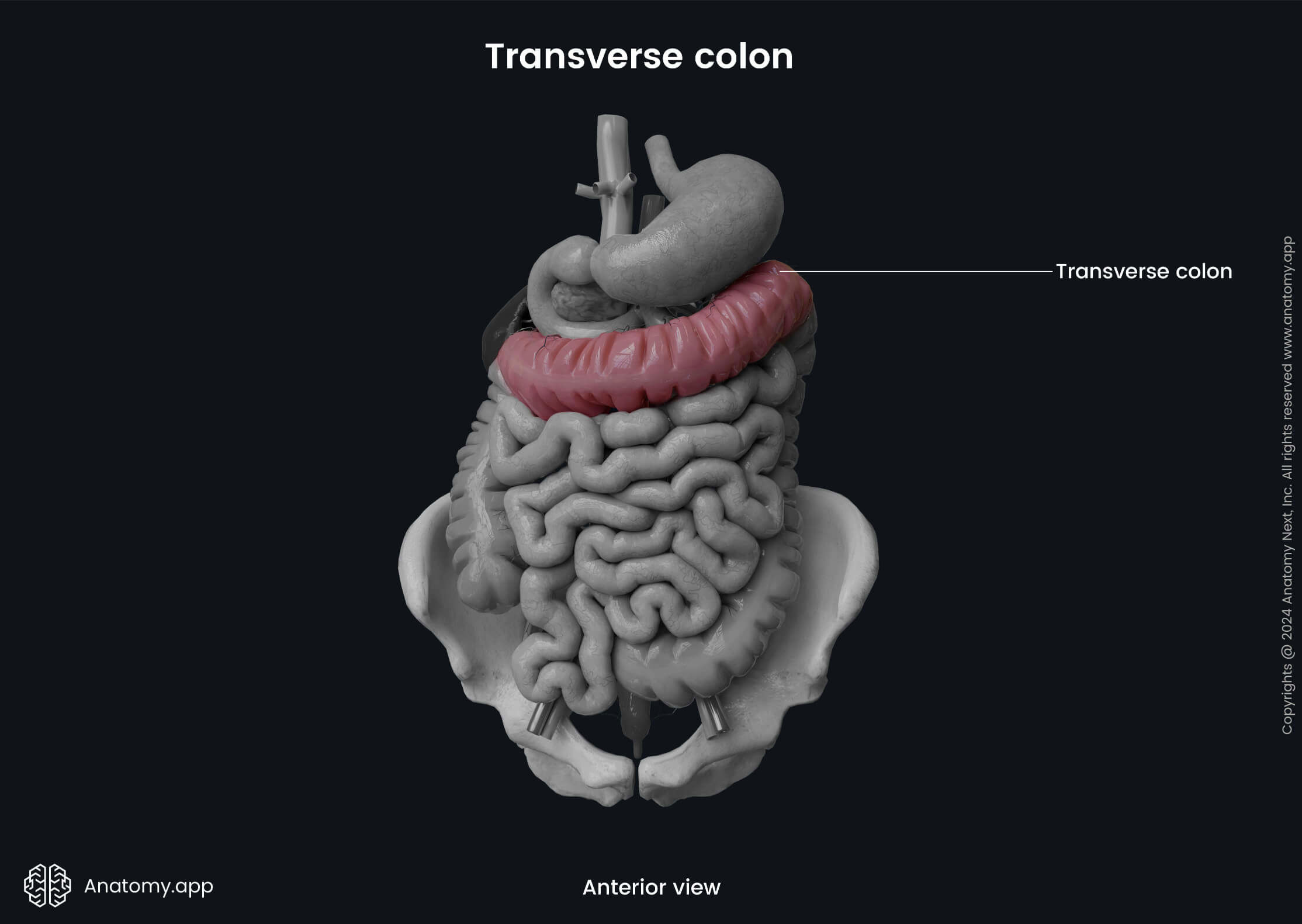

Transverse colon

The transverse colon is the longest segment of the colon and the whole large intestine. It is approximately 16 to 20 inches (40 - 50 cm) long. The transverse colon is a continuation of the ascending colon after it reaches the liver and turns medially and anteriorly, forming the right colic flexure. It then crosses the upper part of the abdominal cavity from the right to the left side. And finally, the transverse colon transitions into the descending colon when it reaches the spleen and forms the left colic flexure.

The left colic flexure (also called the splenic flexure) is usually located more superior. It is less mobile and has a more pronounced angle than the right colic flexure. The left colic flexure marks the junction between the transverse and descending colon and is positioned below the spleen. The phrenicocolic ligament anchors the left colic flexure to the diaphragm at the level of the tenth and eleventh ribs. Posteriorly to the flexure lies the left kidney and the tail of the pancreas.

The transverse colon is fully enveloped in the mesentery - the transverse mesocolon. The root of the mesentery passes along the inferior border of the pancreas and fuses with the parietal peritoneum. Therefore, the transverse colon is an intraperitoneal organ and also the most mobile part of the large intestine. Sometimes it is so loosely fixed that it can even pass down into the pelvic region.

Transverse colon relations

The transverse colon superiorly relates to the liver, gallbladder, greater curvature of the stomach, gastrocolic ligament and spleen. Posteriorly it is suspended from the parietal peritoneum of the posterior abdominal wall by the transverse mesocolon. Also, posteriorly to the transverse colon is the descending part of the duodenum, the head of the pancreas and coils of the jejunum and ileum. The transverse colon is covered by the greater omentum anteriorly, and inferior to it lies the small intestine.

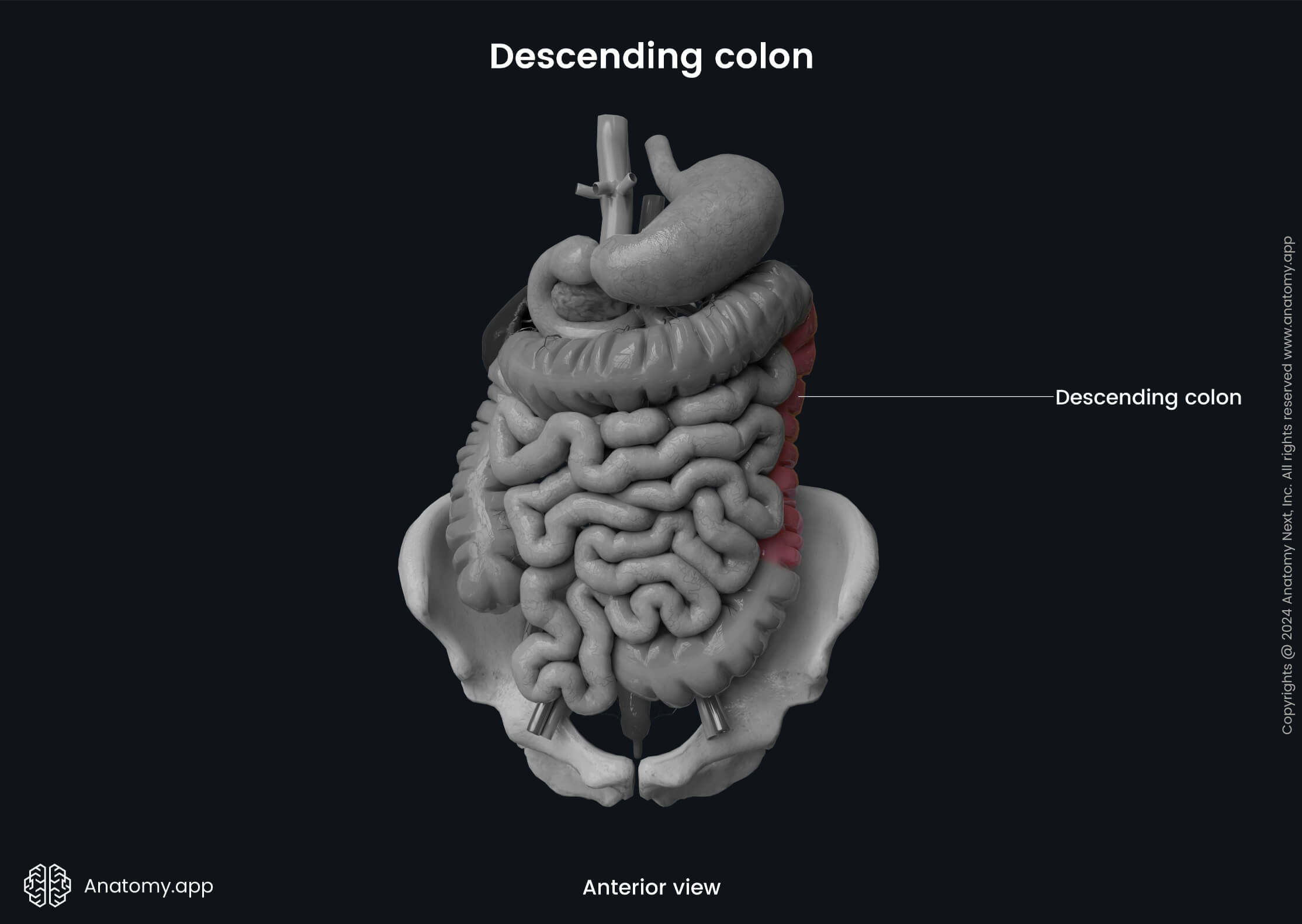

Descending colon

The descending colon extends downward on the left side of the abdominal cavity from the left colic flexure to the level of the iliac crest, where it further continues as the sigmoid colon. It is about 10 to 12 inches (25 - 30 cm) long and is smaller in diameter than the ascending colon. Also, it is situated more deeply and has more pronounced epiploic appendices.

It is a retroperitoneal organ covered by the peritoneum along its anterior and lateral surfaces. The descending colon is typically immobile, but sometimes it can have a short mesocolon (in around 33% of individuals). Therefore, the mesocolon can allow slight mobility.

Descending colon relations

Posteriorly, the descending colon is related to the renal fascia, as well as the quadratus lumborum, transversus abdominis, iliacus and psoas major muscles. Also, several neurovascular structures are located posterior to the descending colon, such as the subcostal arteries, veins and nerves, fourth lumbar artery, iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal, lateral femoral cutaneous, femoral and genitofemoral nerves. Anteriorly, the descending colon contacts loops of the jejunum and is covered by the greater omentum.

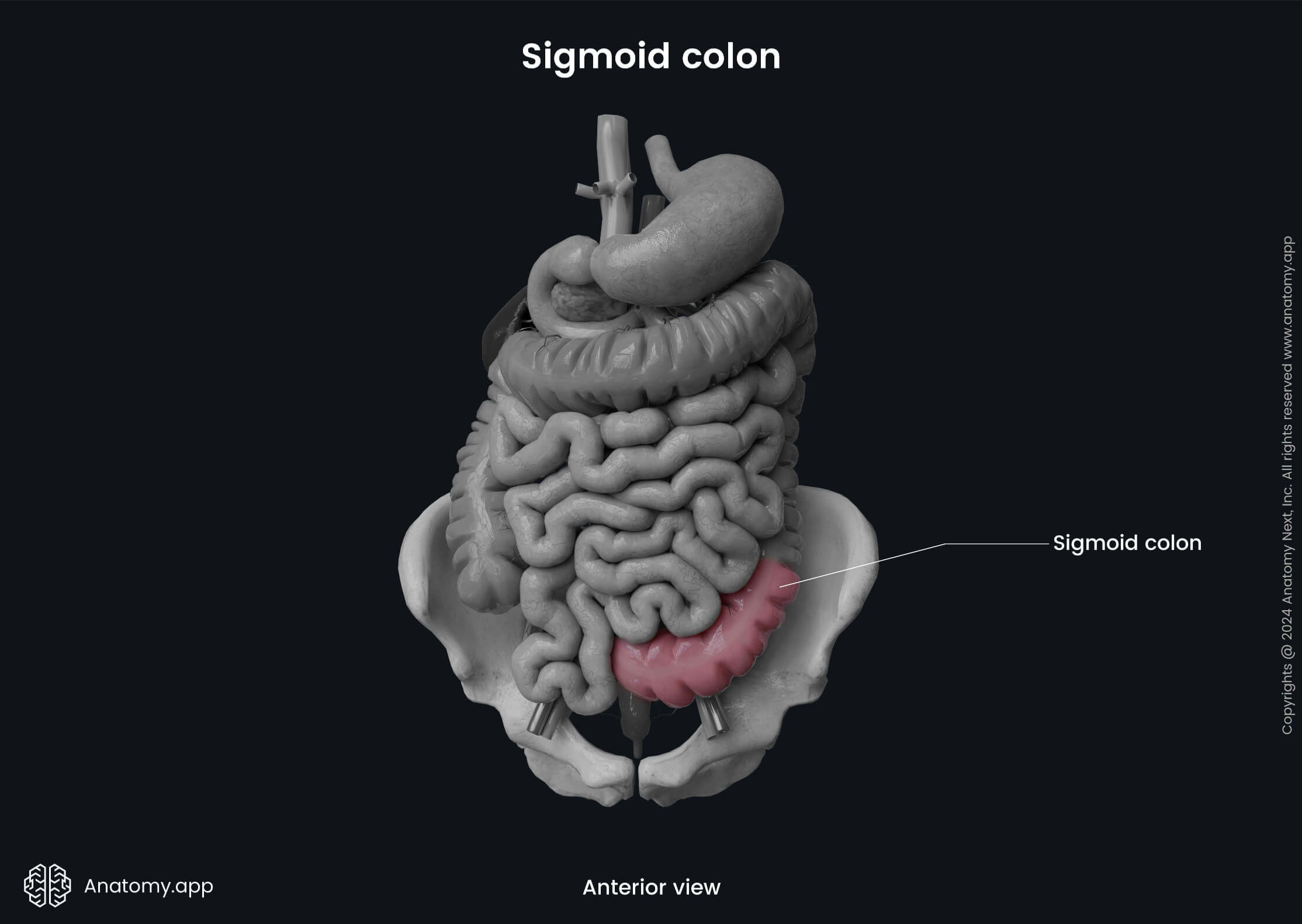

Sigmoid colon

The sigmoid colon is the final S-shaped part of the colon. It is a continuation of the descending colon and varies in length from 6 to 16 inches (15 - 40 cm), averaging around 15 inches (38 cm) in adults. The sigmoid colon starts at the level of the iliac crest and the fossa of the greater pelvis. The peritoneum encircles the sigmoid colon forming its mesentery; therefore, it is a completely intraperitoneal organ.

At the third sacral vertebra (S3) level, the sigmoid colon transitions into the rectum, and this transition site is called the rectosigmoid junction. The rectosigmoid junction is also the site of termination of the taeniae coli and epiploic appendices. It is situated approximately 6 inches or 15 cm from the anus.

The sigmoid colon has wider taeniae coli than those of the other colon parts. They become more scattered and merge together towards the distal aspect of the sigmoid colon, forming a longitudinal muscle layer that extends into the rectum and encircles its walls. The epiploic appendices are particularly more pronounced in the sigmoid colon than in other parts of the colon.

The sigmoid colon is quite mobile because it has a long mesentery called the sigmoid mesocolon. The root of the mesentery has an inverted letter “V” shape, and it attaches the sigmoid colon to the posterior abdominal and pelvic walls. The apex of the letter “V” is located near the site where the left common iliac artery branches into the internal and external iliac arteries.

The right limb of the “V” connects the third sacral vertebra (S3) with the bifurcation of the left common iliac artery. In contrast, the left limb descends from the apex of the “V” along the medial border of the left psoas major muscle and across the external iliac vessels. And finally, it terminates at the level of the inguinal ligament.

Sigmoid colon relations

Posteriorly, the sigmoid colon relates to the left internal iliac artery and vein, and gonadal vessels, left ureter, piriformis muscle, sacrum and the sacral plexus. Laterally to it are the left external iliac artery and vein, left ovary in females or ductus deferens in males, obturator nerve and the lateral pelvic wall. The urinary bladder in males or the uterus and the urinary bladder in females are located anteriorly and inferiorly to the sigmoid colon. And finally, the loops of the ileum lie superiorly and medially to the sigmoid colon.

Neurovascular supply of colon

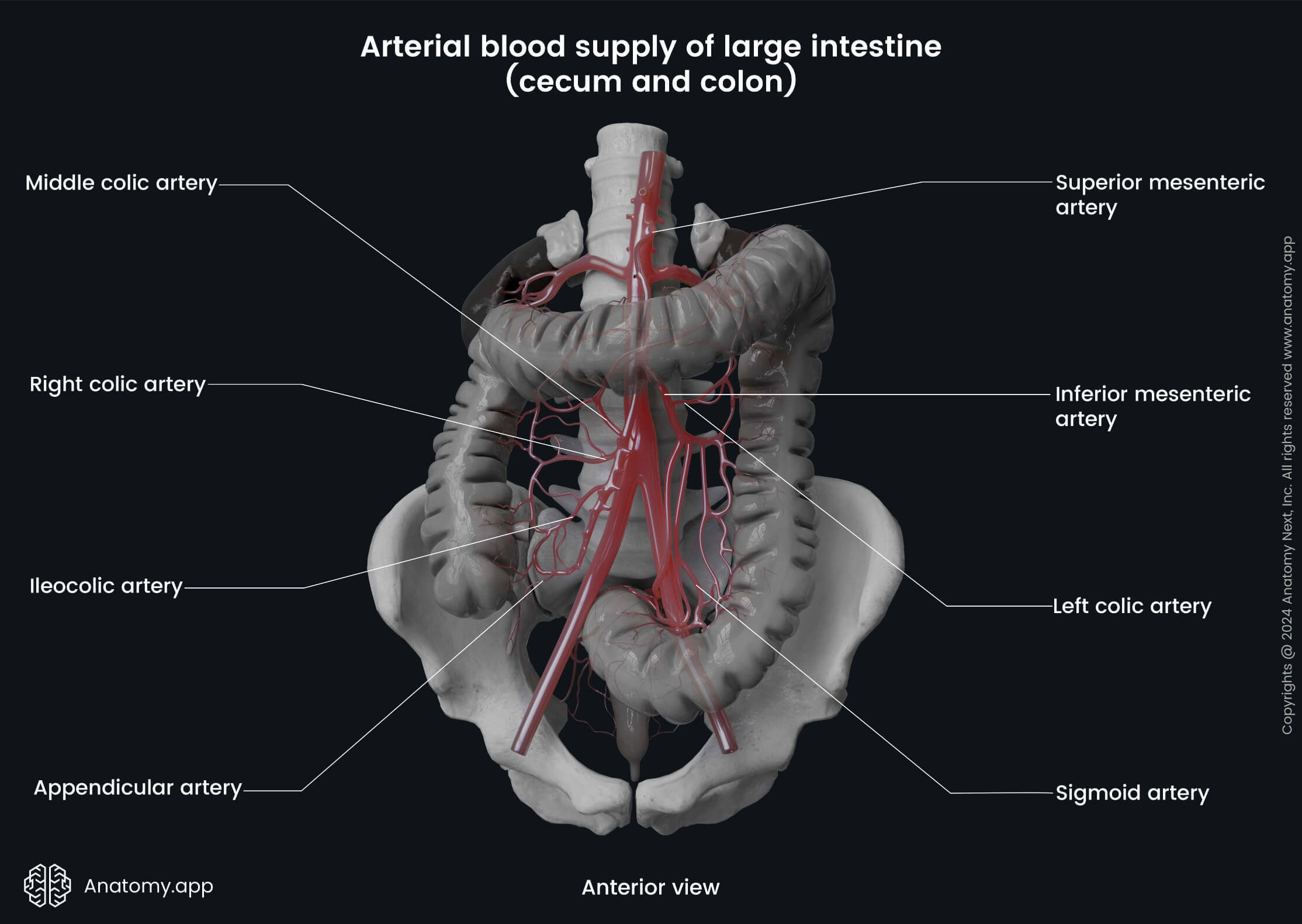

Arterial blood supply

Overall, the arterial blood supply to the colon is provided by the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries. The ascending colon and proximal two-thirds of the transverse colon (derivatives of the midgut) receive arterial supply from the following branches of the superior mesenteric artery:

- Ileocolic artery - perfuses the ascending colon;

- Right colic artery - provides arterial supply to the ascending and transverse colon;

- Middle colic artery - supplies the transverse colon.

The distal third of the transverse colon, descending colon, and sigmoid colon (the hindgut derivatives) are supplied by the branches of the inferior mesenteric artery:

- Left colic artery - perfuses the descending colon

- Sigmoid arteries - provides supply to the sigmoid colon.

Note: During the embryological period, the gastrointestinal tract organs are derived from the primitive gut tube, which is divided into three portions: foregut, midgut and hindgut. Each of the portions is distinct in its embryological development and neurovascular supply. The foregut develops later into the esophagus, stomach, liver, gallbladder, pancreas, and the first part of the duodenum. The midgut develops into the rest of the duodenum, small intestine, and large intestine up to the proximal two-thirds of the transverse colon. Finally, the hindgut is the derivative of the remaining part of the large intestine up to the upper anal canal.

The superior and inferior mesenteric arteries communicate with each other via several anastomoses. One of them is formed between the middle colic artery and the left colic artery. However, it can be formed directly between the proximal superior mesenteric artery and the proximal inferior mesenteric artery. It is an inconstant anastomosis, and it is called the arc of Riolan or the central anastomotic mesenteric artery.

Also, both arteries communicate through a unified anastomotic vessel called the marginal artery (also known as the marginal artery of Drummond). It runs parallel to the length of the colon from the ileocecal to the rectosigmoid junction. The main arteries forming the marginal artery are branches of the superior mesenteric artery (ileocolic, right colic and middle colic arteries) and the left colic artery (left colic artery and sigmoid arteries). It is more pronounced in the ascending, transverse and descending colon. The sigmoid colon has a poorly developed marginal artery.

The marginal artery is located along the inner border of the colon, giving off numerous short branches that go toward the intestinal wall. They are called the straight arteries or vasa recta. The vasa recta can be subdivided into the short vasa recta, which run through the muscular layer and the long vasa recta, which go through the subserosa and muscular layer, also supplying the epiploic appendices.

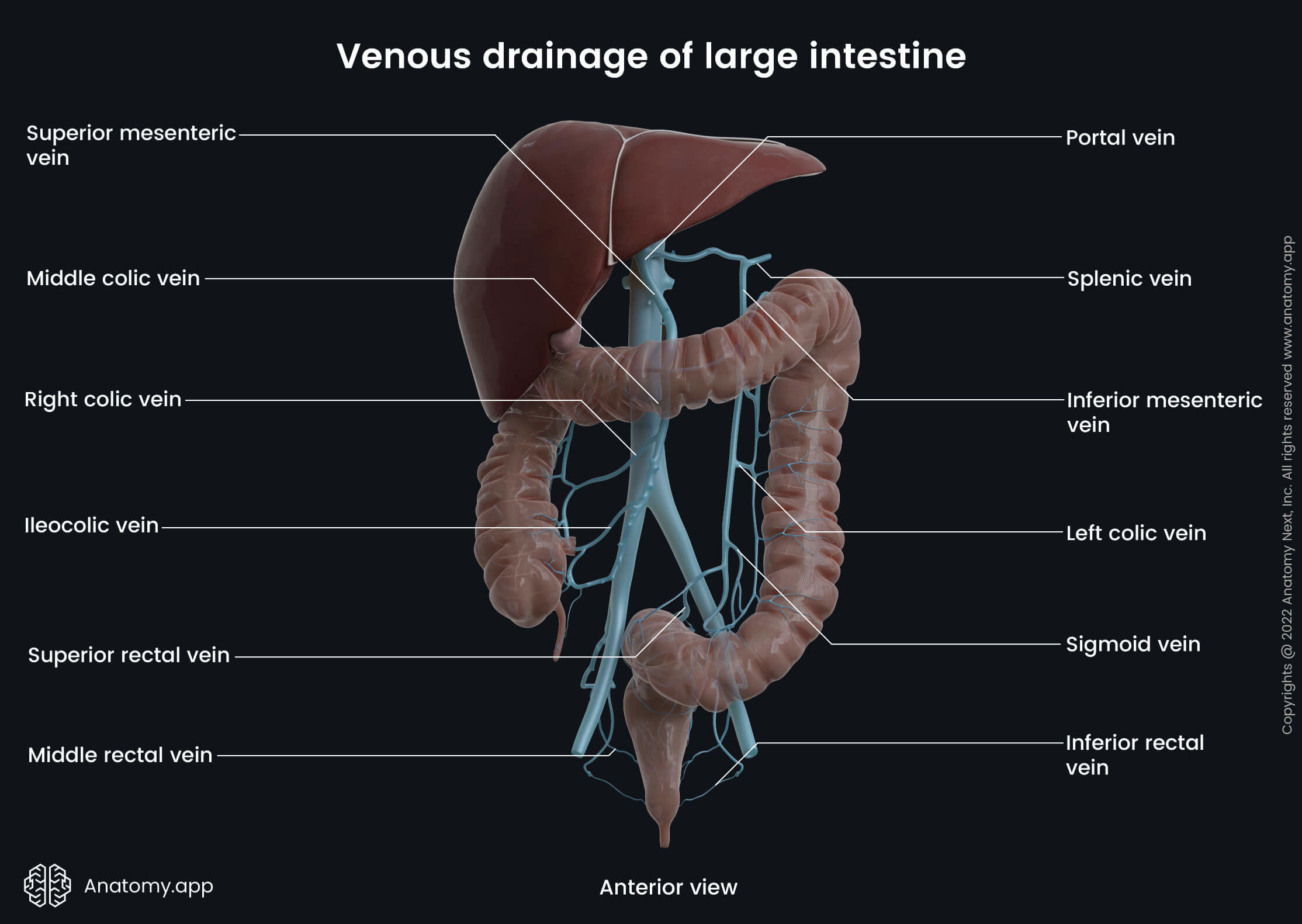

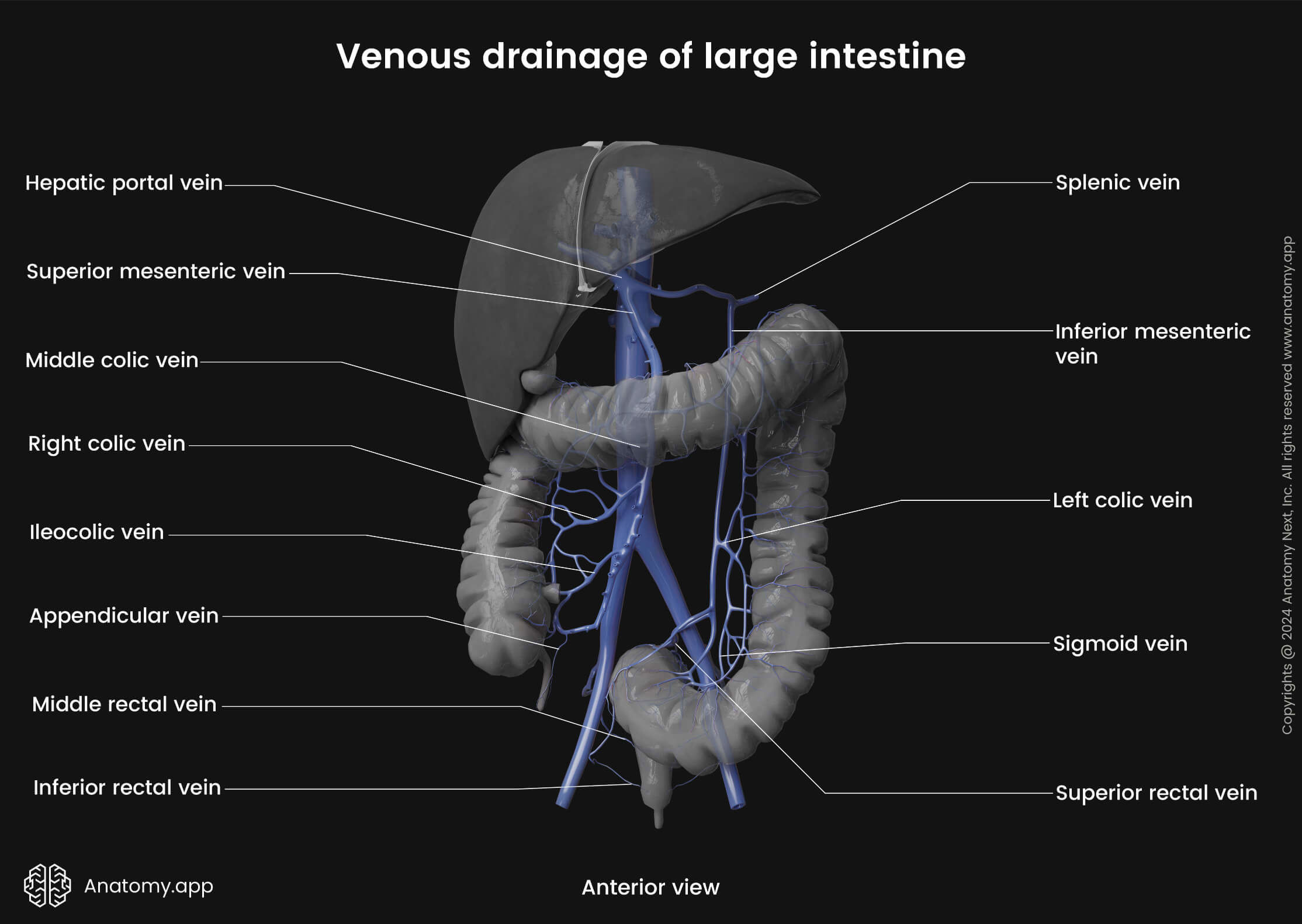

Venous drainage

The venous drainage of the colon is provided by the hepatic portal system via the superior and inferior mesenteric veins. Blood collected from the midgut derivatives (ascending colon and proximal two-thirds of the transverse colon) drains into the colic branches (ileocolic, right colic, middle colic veins) of the superior mesenteric vein.

In contrast, the hindgut derivatives (distal third of the transverse colon, descending colon and sigmoid colon) are drained by the left colic and sigmoid veins that flow into the inferior mesenteric vein. Further, the inferior mesenteric vein carries blood to the splenic vein, while the superior mesenteric vein joins the splenic vein and forms the hepatic portal vein.

Innervation

The innervation of the colon is very complex, and it comes from the intrinsic and extrinsic neurons that form intrinsic and extrinsic nervous systems, respectively. The intrinsic nervous system is located and formed within the colon. It is interwoven in the colon walls, and it includes the enteric nervous system consisting of two nerve plexuses that provide local autonomous functions. However, the intrinsic system also receives input from the extrinsic nervous system.

In contrast, the extrinsic nervous system includes efferent and afferent nerves that primarily come from external sources. They originate from either the brain or spinal cord of the central nervous system. The extrinsic nervous system includes the autonomic nervous system with sympathetic and parasympathetic nerve fibers.

Enteric nervous system

The enteric nervous system is made up of two nerve plexuses. Overall, they control intestinal motility (rhythmic movement of food through the intestines) and smooth muscle cells, fluid exchange, intestinal gland secretion and local blood flow. Also, this system modulates immune and endocrine functions. The plexuses are as follows:

- Submucosal plexus (also called the Meissner’s plexus)

- Myenteric plexus (also known as the Auerbach’s plexus)

The submucosal plexus is located within the submucosa. It contains non-myelinated postganglionic sympathetic fibers and parasympathetic ganglion cells. The submucosal plexus innervates the muscularis mucosae, as well as the crypts of Lieberkühn, ensuring the secretion of the intestinal glands.

The myenteric plexus is positioned in the muscularis externa between its circular and longitudinal layers. It is composed of sympathetic and parasympathetic fibers that innervate both layers of the muscularis propria and therefore control the motility (movement) of the intestinal wall.

Autonomic nervous system

The autonomic nervous system ensures sympathetic and parasympathetic nerve supply. Sympathetic innervation of the colon is provided by the thoracic, lumbar and sacral splanchnic nerves. The sympathetic fibers are responsible for vasoconstriction of the intestinal blood vessels and relaxation of the muscle cells within the wall of the colon.

The bodies of the preganglionic sympathetic neurons supplying the midgut derivatives (ascending colon and proximal two-thirds of the transverse colon) are located in the gray matter of the fifth to twelfth thoracic segments (T5 - T12) of the spinal cord. The axons of these neurons form the greater and lesser thoracic splanchnic nerves that travel to the celiac and superior mesenteric plexuses, where they synapse with the neurons of the celiac and superior mesenteric ganglia. The postganglionic axons then reach the colon and form the periarterial plexuses around the branches of the superior mesenteric artery.

The bodies of the preganglionic sympathetic neurons supplying the hindgut derivatives (distal one-third of the transverse colon, descending colon and sigmoid colon) are located in the gray matter of the first and second lumbar segments (L1 - L2) of the spinal cord. The axons of these neurons form the lumbar and sacral splanchnic nerves. The lumbar splanchnic nerves synapse with the neurons in the aortic and inferior mesenteric plexuses. The sacral splanchnic nerves synapse with the neurons in the superior and inferior hypogastric plexuses. The postganglionic axons form the periarterial plexuses around the branches of the inferior mesenteric artery.

The parasympathetic innervation of the colon is ensured by fibers of the vagus nerve (CN X). The parasympathetic fibers activate mucus secretion from the intestinal glands and provide contraction of the intestinal muscle cells. The midgut derivatives receive nerve supply from branches of the vagus nerve via the celiac and superior mesenteric plexuses. Branches of the vagus nerve that extend from the second to fourth sacral spinal cord segments (S2 - S4) innervate the hindgut derivatives via the pelvic splanchnic nerves that reach the inferior hypogastric plexus.

Lymphatic drainage

The lymphatic drainage of the colon is provided by lymphatic vessels (lymphatics) and lymph nodes that mostly run along the course of the arteries. The lymph collected from the ascending colon and proximal transverse colon is drained to the lymph nodes located along the superior mesenteric artery. In contrast, lymph from the region of the distal transverse colon, descending colon and sigmoid colon drains into the lymph nodes located around the inferior mesenteric artery.

There are four groups of lymph nodes related to the colon:

- Epicolic

- Paracolic

- Intermediate colic

- Preterminal colic

The epicolic lymph nodes are small nodules located on the serosal surface of the colon, and sometimes they can even be found inside the epiploic appendices. The paracolic lymph nodes are situated along the medial margin of the ascending and descending colon and also at the mesenteric margins of the transverse colon and sigmoid colon.

The intermediate colic lymph nodes lie along the branches of the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries, and they include the ileocolic, right colic, middle colic, left colic and sigmoid lymph nodes. The preterminal colic lymph nodes are located along both major arteries that supply the colon - superior and inferior mesenteric arteries. The lymph from the superior and inferior mesenteric lymph nodes drains into the intestinal lymph trunk before reaching the cisterna chyli. And finally, from the cisterna chyli, it is carried to the thoracic duct.

Colon histology

The wall of the colon consists of the following layers:

- Mucosa

- Submucosa

- Muscularis externa (or propria)

- Serosa

Mucosa

The mucosa (or mucosal layer) is the inner layer that faces the lumen of the colon. It is made up of three sublayers - epithelium, lamina propria and muscularis mucosae.

The mucosa is lined by simple columnar epithelium. Besides the columnar intestinal epithelial cells called colonocytes, the epithelium also contains goblet cells that secrete mucus, enteroendocrine cells that produce hormones and microfold cells (M cells) that are rare specialized intestinal epithelial cells found overlying the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT). M cells phagocytose (ingest) and transport antigen cells.

The colonocytes primarily provide absorptive function. The apical ends of the colonocytes are covered by small projections called microvilli. Microvilli of the colon are shorter than those of the small intestine. The intestinal glands (also called the crypts of Lieberkühn) are more numerous compared to the small intestine. They project deep into the lamina propria.

The lamina propria is a layer of loose connective tissue that provides structural support to the mucosal epithelium. The lamina propria also contains many structures that provide absorptive and immunological functions. It includes solitary lymphoid follicles, which are less pronounced in the colon than in the small intestine, as well as the lamina propria contains blood and lymph vessels, nerve fibers and such immune cells as neutrophils, lymphocytes, macrophages and other.

The muscularis mucosae is the muscular layer located at the base of the mucosa. It separates the mucosa from the submucosa. The muscularis mucosae consists of two distinct layers of smooth muscle cells - the inner is circular, while the outer is longitudinal. The muscularis mucosae of the colon is slightly thicker than the same layer of the small intestine. Its thickness progressively increases from the beginning of the colon toward the rectum.

Submucosa

The submucosa or submucosal layer of the colon is formed by loose connective tissue infiltrated by such cells as the fibroblasts, macrophages, plasma cells, mast cells and lymphocytes. It also contains blood vessels, lymphatics and the submucosal nerve plexus called Meissner’s plexus.

Muscularis externa

The muscularis externa (also known as the muscularis propria) lies beneath the submucosa and is composed of two distinct sublayers of smooth muscle cells. The outer is the longitudinal layer, and the inner is the circular layer. The muscle fibers of the longitudinal layer form previously described longitudinal bands known as the taeniae coli. The circular muscular layer, on the other hand, forms a thin layer that encircles the lumen of the colon. Between both muscular layers lies the myenteric nerve plexus (Auerbach’s plexus).

Serosa

The serosa or serous membrane is the outermost layer of the colonic wall. It is formed by the visceral peritoneum that is lined by the simple squamous epithelium called the mesothelium. The mesothelium is supported by loose connective tissue that is found beneath it. The serosa also includes epiploic appendices that are more pronounced on the transverse colon and sigmoid colon.

Colon functions

The main functions of the colon are the following:

- Absorption of remaining water and electrolytes (such as potassium and chloride);

- Propulsion of gut content through the entire colon;

- Formation of feces;

- Production and absorption of some vitamins (K and B, for example, B7 - biotin);

- Temporary storage of feces before they are pushed into the rectum.

Around 1.5 to 2 liters of fluid pass through the ileocecal valve each day. Although the majority of the fluid is already absorbed in the small intestine, the colon takes up only around 400 ml and is capable of absorbing approximately 90% of the fluid passing through to it. The absorption of fluids is stimulated by the transport of sodium, chloride and bicarbonate ions through the membrane, as well as by a process called osmosis, where water molecules diffuse from a region of high water potential to a region of low water potential.

Recently, a significant role in water absorption has also been attributed to short-chain fatty acids produced predominantly on the right side of the colon by bacterial metabolism of dietary fiber. The bacteria of the colon produce substantial amounts of some vitamins, such as vitamin K and vitamin B7, that are later absorbed into the bloodstream. When a diet lacks these vitamins, the colon and its bacteria have a crucial role in their fermentation and production.

The motor activity of the colon can be characterized by rhythmic contractions of the smooth muscle fibers within the intestinal wall. These contractions are crucial as they provide the formation of feces and their movement toward the rectum. From the rectum, they can be expelled into the external environment through the anal canal and anus.

The motor activity of the colon is usually greater during the day. Also, the colon is more active after waking up and eating meals. Usually, it takes about 24 - 48 hours for digested food to move through the colon. However, the time depends on the food type, and it is defined as the colonic transit time.

References:

- Drake, R., Vogl, W., & Mitchell, A. (2019). Gray’s Anatomy for Students: With Student Consult Online Access (4th ed.). Elsevier.

- Gray, H., & Carter, H. (2021). Gray’s Anatomy (Leatherbound Classics) (Leatherbound Classic Collection) by F.R.S. Henry Gray (2011) Leather Bound (2010th Edition). Barnes & Noble.

- Moore, K.L., Dalley, A.F., Agur, A.M. (2018). Clinically Oriented Anatomy, 8th Edition, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

- Townsend, C. M., Jr. (2021). Sabiston Textbook of Surgery. Elsevier Gezondheidszorg.