- Anatomical terminology

- Skeletal system

- Joints

- Muscles

- Heart

- Blood vessels

- Lymphatic system

- Nervous system

- Respiratory system

- Digestive system

- Urinary system

- Female reproductive system

- Male reproductive system

- Endocrine glands

- Eye

- Ear

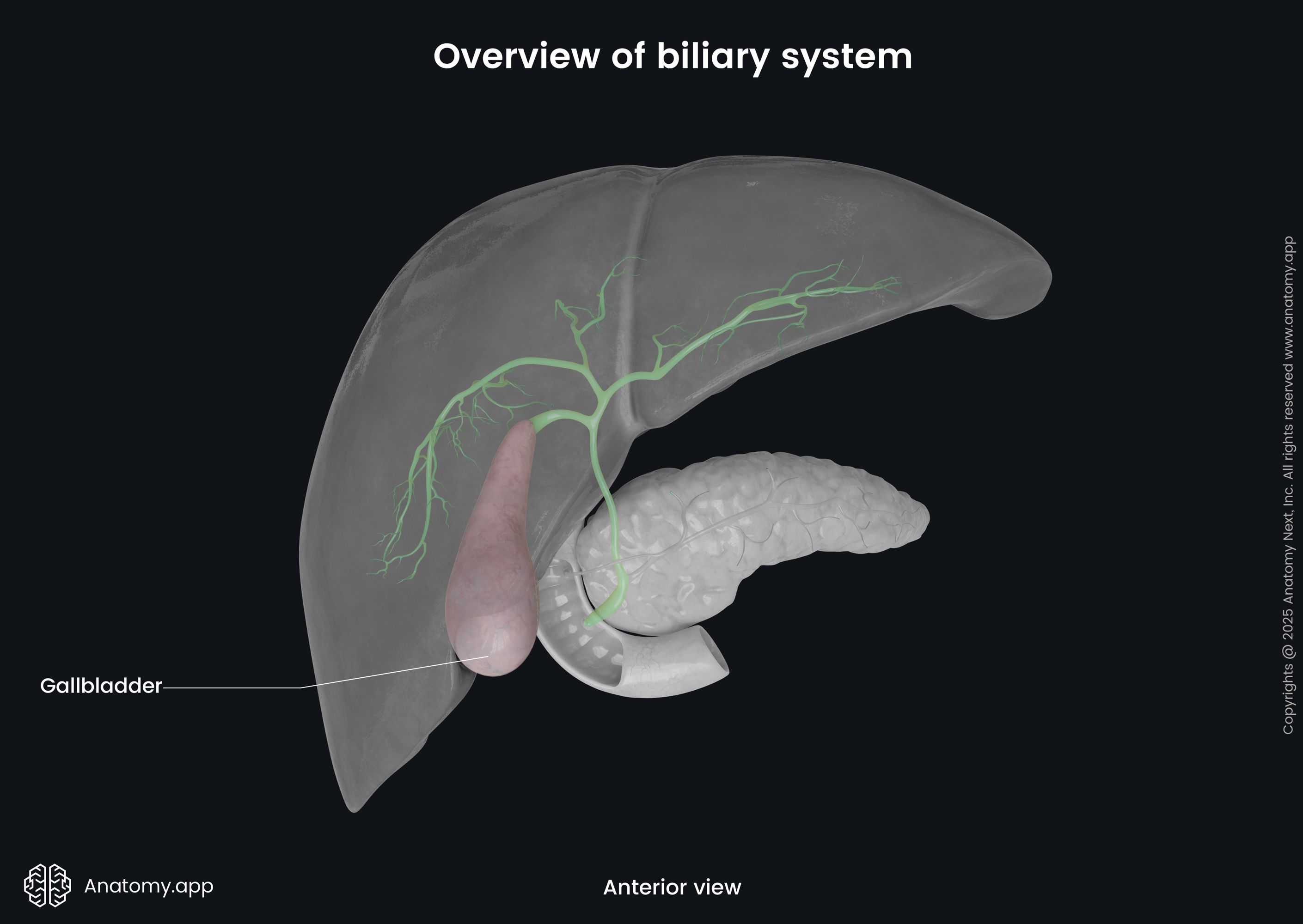

Gallbladder and biliary tree

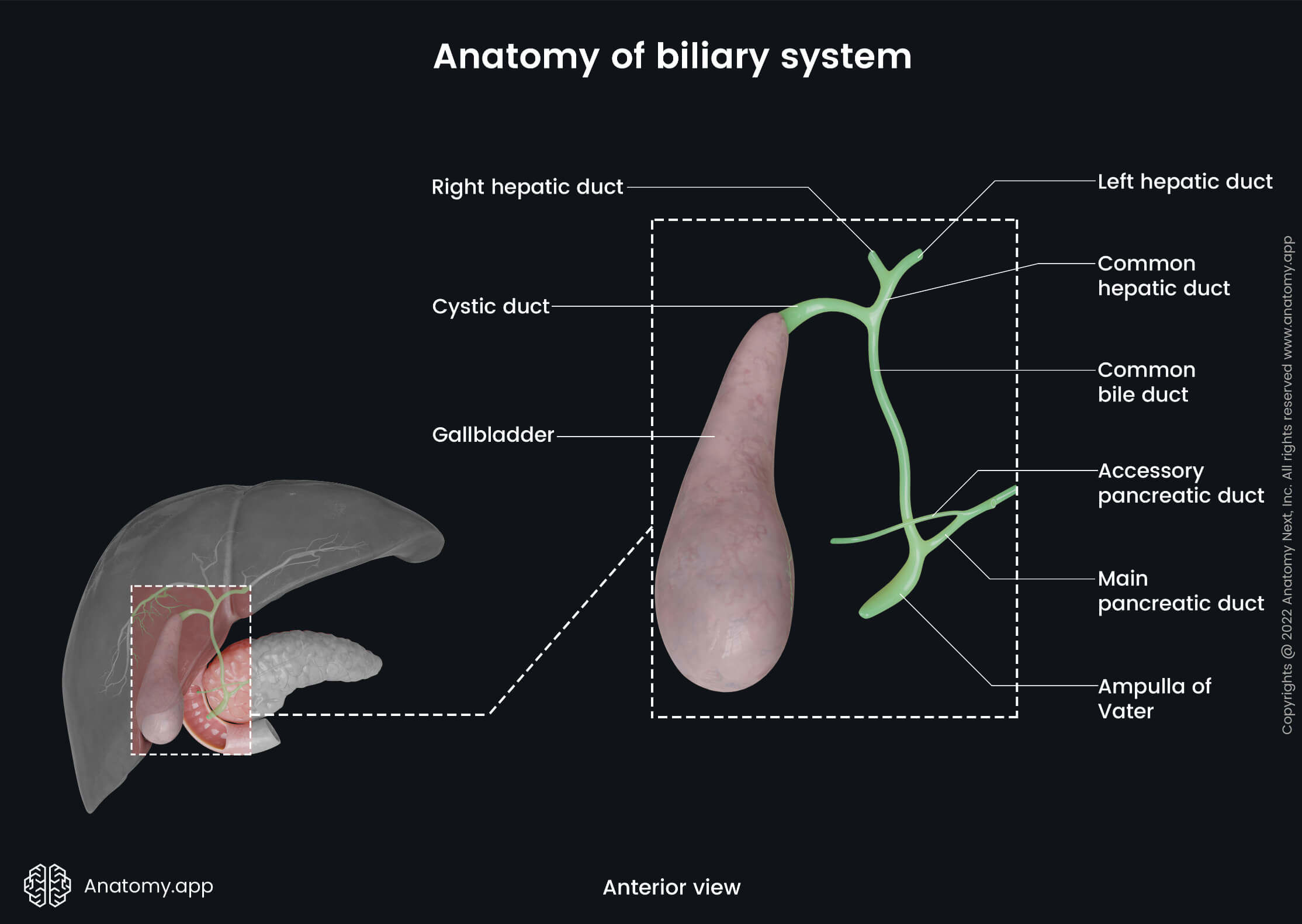

The biliary tree (also known as the biliary system, biliary tract) is a system of ducts that collect and transport bile from the liver to the duodenum. Bile is a yellowish-green liquid that helps with digesting fats in the small intestine. It is stored and concentrated in the gallbladder - a pear-shaped sac-like organ located on the inferior surface of the liver. It is 7 - 10 cm long and can store 25 - 50 ml volume of bile. The gallbladder is connected to the common bile duct via the cystic duct. The bile is then further released into the descending part of the duodenum to aid in the digestion of fats by breaking them into smaller fat droplets. This process happens in response to a hormone called cholecystokinin secreted by cells of the duodenum.

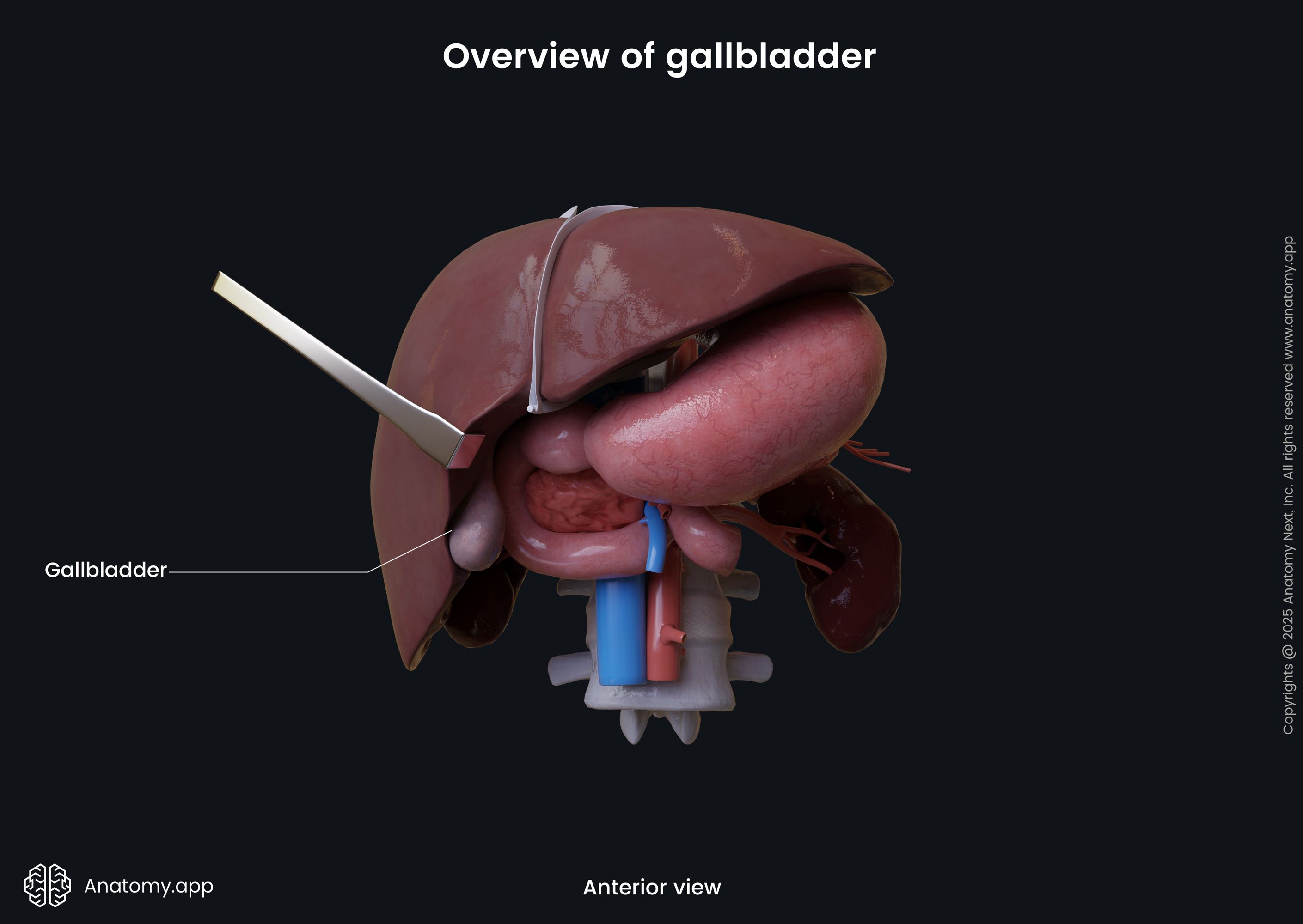

Gallbladder anatomy

The gallbladder (Latin: vesica biliaris) is located on the inferior aspect of the right lobe of the liver in a fossa that separates the right lobe from the quadrate lobe of the liver, known as the fossa for the gallbladder. It is attached to the liver by connective tissue. The peritoneum of the liver also extends to the gallbladder covering it, except for the surface facing the liver.

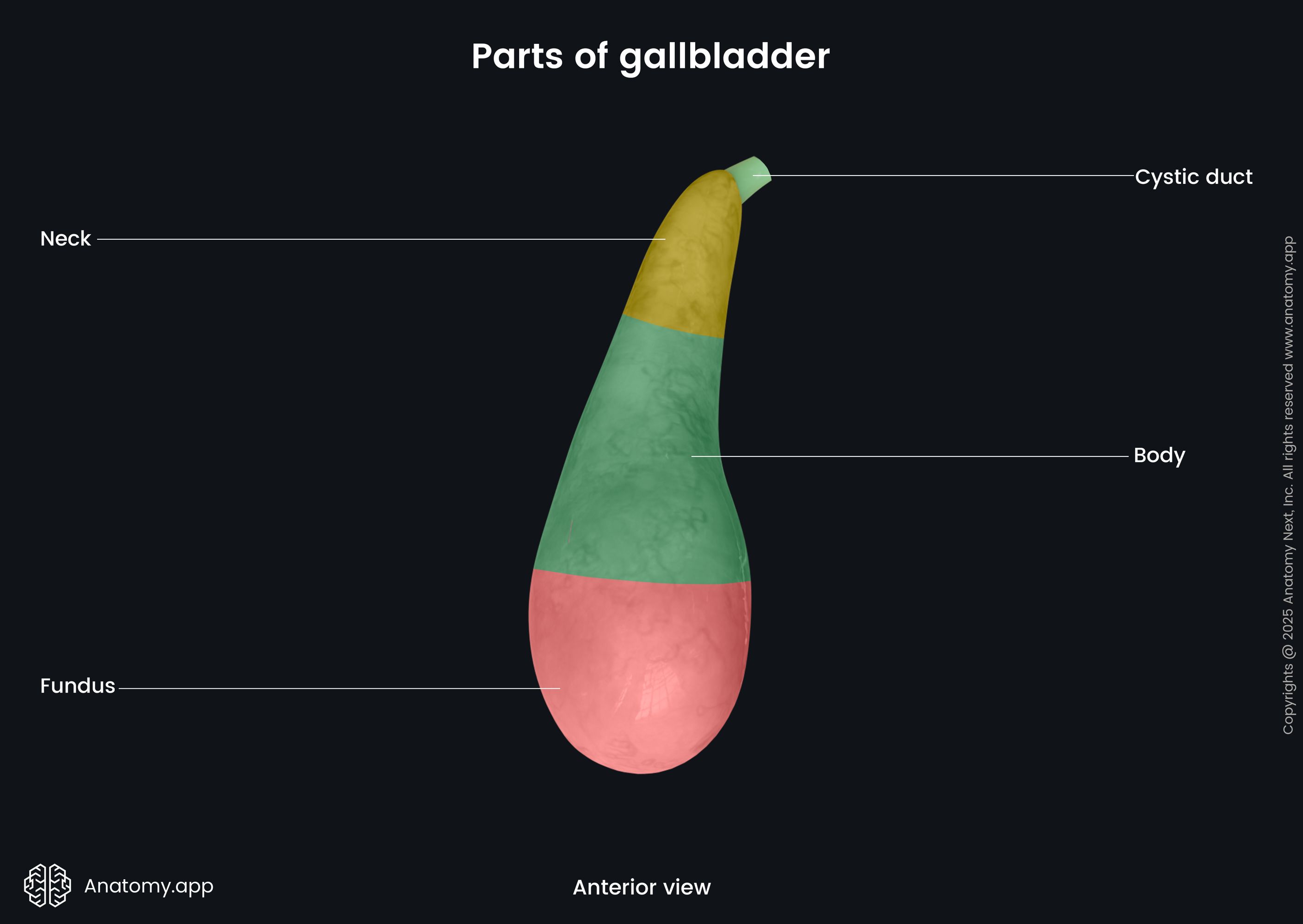

The gallbladder can be divided into three anatomical parts: fundus, body and neck. The fundus is the lateral rounded end of the gallbladder. It often extends outside the inferior border of the liver. Here it relates to the transverse colon and contacts the anterior abdominal wall. The body of the gallbladder is the largest part located in the fossa for the gallbladder. The body of the gallbladder usually relates to the right colic (hepatic) flexure, the proximal end of the transverse colon and the descending part of the duodenum posteriorly.

Note: When enlarged, the fundus of the gallbladder can sometimes be felt by touch (palpated) at the site where the lateral border of the right rectus abdominis muscle crosses the right costal arch, approximately at the ninth costal cartilage level.

The neck of the gallbladder is the narrow medial part that continues with the cystic duct and lies close to the porta hepatis. Usually, the neck has a mesentery attachment with the liver, where the cystic artery is located. The neck of the gallbladder borders with the superior part of the duodenum posteriorly. The distal part of the gallbladder neck contains oblique ridges that are continuous with the spiral valves of Heister. The Heister valves are mucosal folds found within the proximal mucosa of the cystic duct.

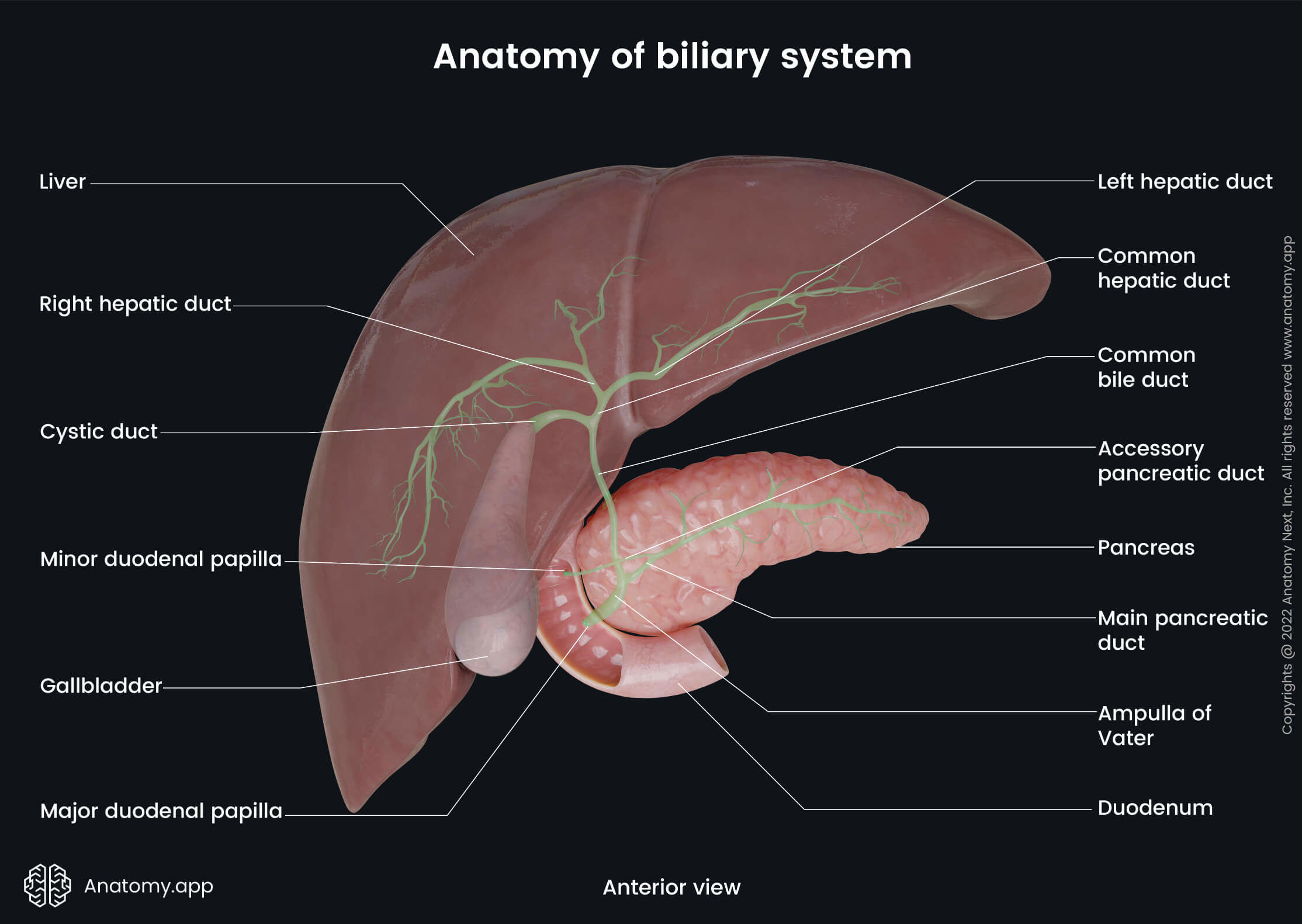

Biliary tree anatomy

The biliary tree is composed of two parts - the ducts that are found inside the liver (intrahepatic) and ducts located outside the liver (extrahepatic).

Intrahepatic biliary tree

The intrahepatic biliary tree is formed by bile canaliculi, canals of Hering, bile ductules and various ducts surrounded by hepatic and connective tissue cells. The smallest unit of the intrahepatic biliary tree is the bile canaliculus (bile capillary). It is a thin bile tube surrounded by hepatocytes, and it receives and collects hepatocyte-secreted bile. The canal of Hering is a larger intrahepatic bile ductule surrounded by three types of cells - hepatocytes, cholangiocytes and hepatic progenitor (stem) cells, while bile ductules are intrahepatic bile tubes that are lined only by the cholangiocytes.

Various bile ductules join together, forming interlobular bile ducts, then these merge into area bile ducts that further form segmental bile ducts. The segmental ducts combine to form sectoral ducts. And finally, sectoral bile ducts fuse and create the right and left hepatic ducts. All ductules and ducts smaller than area bile ducts are considered small bile ducts, while all tubes larger than area bile ducts are classified as large bile ducts. The left hepatic duct is formed by the unification of the ducts from liver segments 2 and 3. The left hepatic duct is located next to the umbilical part of the left hepatic portal vein. Segments 4 and 1 are drained by additional ducts flowing into the left hepatic duct.

The right hepatic duct is formed by merging the right anterior (medial) and right posterior (lateral) sectoral ducts. The right anterior (medial) sectoral duct collects bile from segments 5 and 8. The right posterior (lateral) sectoral duct drains segments 6 and 7. An additional bile duct draining segment 1 can join the right posterior (lateral) sectoral duct. Typically, the right hepatic duct, together with adjacent blood vessels, lies in the Rouviere’s sulcus (also called fissure of Gans or incisura hepatis dextra). It is located on the visceral surface of the right lobe posterior to the gallbladder fossa and on the right side of the porta hepatis. Posteriorly it borders with segment 1 and anteriorly - with the fossa of the gallbladder.

The intrahepatic duct pattern described above is considered typical and is found in more than half of the world’s population. Some anatomical variations may be present. There is no right hepatic duct in about 10 - 15% of people, and a trifurcation pattern is found. In this case, three ducts - the right anterior (medial) sectoral, right posterior (lateral) sectoral and left hepatic ducts - join together and form the common hepatic duct. In another 10 - 15% of cases, one of the right sectoral ducts (typically the right posterior (lateral) sectoral) merges with the left hepatic duct.

Extrahepatic biliary tree

The extrahepatic biliary tree is formed by the extrahepatic segments of the right and left hepatic ducts, common hepatic duct, cystic duct, gallbladder and the common bile duct. The segment of the right hepatic duct outside the liver is short, while the left hepatic duct is longer and situated more horizontally.

The right and left hepatic ducts unite and form the common hepatic duct - about 3 - 4 cm long tube. The common hepatic duct descends and joins the cystic duct on its right to form the common bile duct. The common hepatic duct is located in the hepatoduodenal ligament together with the proper hepatic artery (on the left side) and hepatic portal vein (posterior).

The cystic duct is approximately 2 - 4 cm long. It emerges from the neck of the gallbladder, runs posteroinferiorly and to the left to join the common hepatic duct. The mucosa of the proximal cystic duct consists of 2 to 10 crescent-shaped folds creating spiral-shaped valves (valves of Heister). Mucosal folds of the cystic duct join the folds in the neck of the gallbladder. The exact function of these folds is still being disputed. It is hypothesized that they can preserve the patency of the duct rather than regulate the bile flow.

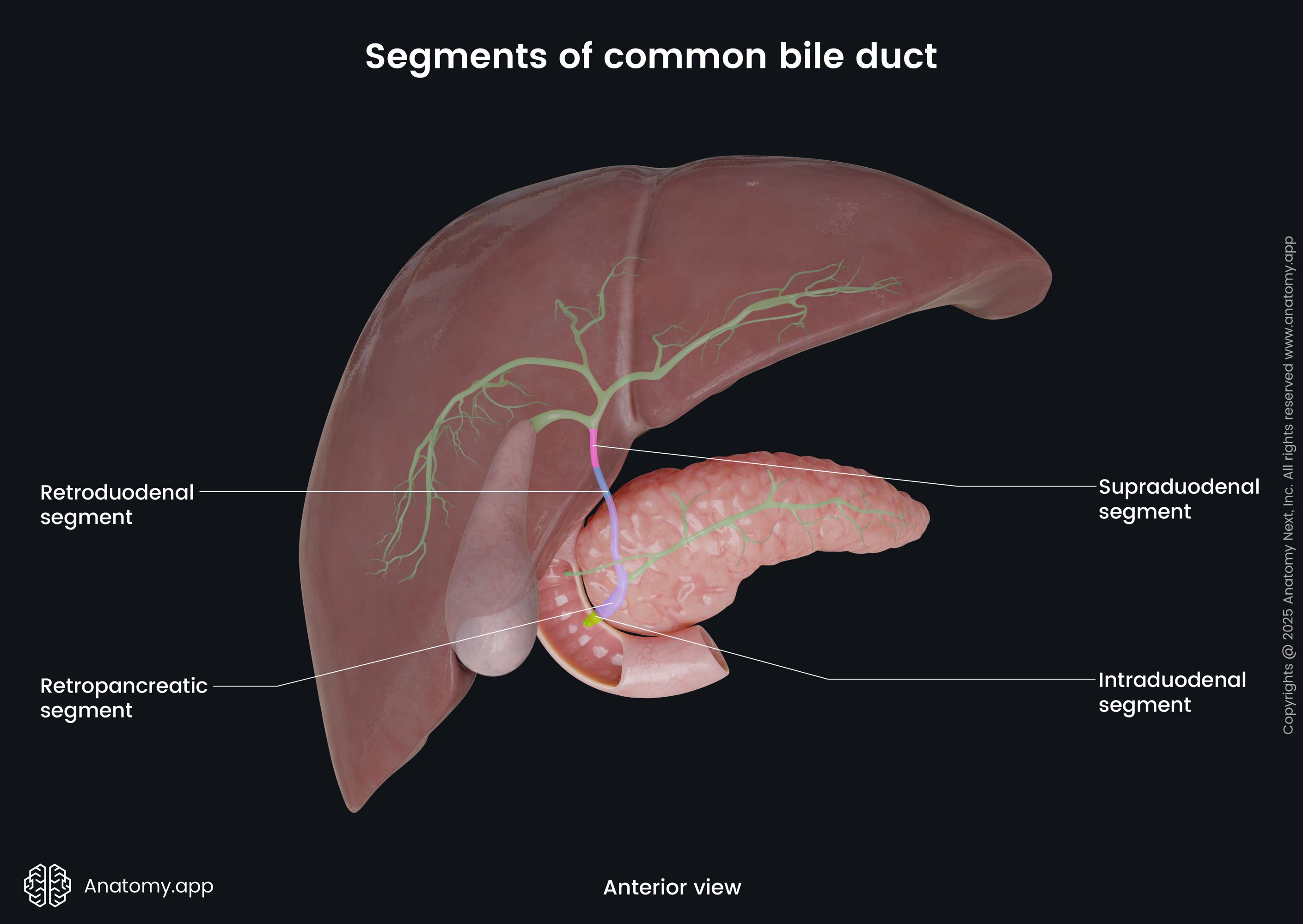

The common bile duct is formed by the union of the cystic duct and common hepatic duct. It starts near the porta hepatis and is 6 to 8 cm long. The common bile duct is divided into four segments or parts according to their localization:

- Supraduodenal segment

- Retroduodenal segment

- Retropancreatic segment

- Intraduodenal segment

The supraduodenal segment is located within the hepatoduodenal ligament together with the proper hepatic artery and hepatic portal vein. This part of the common bile duct is the easiest to access during surgery. The supraduodenal segment runs above the superior (first) part of the duodenum.

The retroduodenal segment is located behind the superior part of the duodenum to the right of the gastroduodenal artery. The posterior superior pancreaticoduodenal artery - a branch of the gastroduodenal artery - crosses the retroduodenal segment anteriorly.

The retropancreatic segment goes down on the posterior surface of the pancreatic head and runs to the right side to reach the descending (second) part of the duodenum. The retropancreatic part sometimes forms a groove on the pancreatic head. The retropancreatic segment is also referred to as the intrapancreatic segment because, most often, tissues of the pancreas surround and cover this segment.

As the common bile duct approaches the main pancreatic duct, both ducts pierce the wall of the duodenum and merge in a Y-shaped configuration. This configuration forms a several-millimeters-long common channel. The channel contains a dilation called the hepatopancreatic ampulla (ampulla of Vater). It terminates with an opening in the posteromedial wall of the descending part of the duodenum. The duodenal wall contains a slight mucosal elevation at the opening site called the major duodenal papilla (or papilla of Vater). The mucosa in the terminal part of the duct contains circumferential folds that have an anti-reflux function. The short portion of the common bile duct that goes through the wall of the duodenum is called the intraduodenal segment.

The walls of the distal parts of the common bile duct, main pancreatic duct and hepatopancreatic ampulla contain smooth muscle cells. The circumferential organization of these muscle cells forms three sphincters: a sphincter of the common bile duct (of Boyden), a sphincter of the main pancreatic duct and a sphincter of the hepatopancreatic ampulla (sphincter of Oddi). These sphincters regulate the flow of bile and pancreatic secretions and contribute to the anti-reflux system of the duodenal contents.

Gallbladder and biliary tree histology

The microstructure of the gallbladder wall is similar to that of the small intestine. It contains three layers:

- Mucosa

- Outer muscular layer (muscularis propria)

- Adventitia or serosa

The mucosa contains many irregular folds, and it gives a wrinkled appearance. When the gallbladder is filled with bile, these folds become flattered as the outer muscular layer helps to stretch the gallbladder wall. The mucosa is lined by one layer of columnar cells (simple columnar epithelium) containing apical microvilli that extend into the lumen of the gallbladder. The epithelial cells are responsible for absorbing water and solutes (such as sodium, chloride and bicarbonate ions) from the bile. The gallbladder wall does not present a muscularis mucosae layer and distinct submucosa. The epithelial cells rest on a thin basal lamina. Underneath it lies lamina propria containing blood and lymphatic vessels, as well as a thin layer of loose connective tissue.

The outer muscular layer (muscularis propria) is relatively thin, and it contains smooth muscle fibers and connective tissue. The muscle cells go in different directions throughout the wall of the gallbladder, and there are no distinct circular or longitudinal muscle layers. Muscularis propria ensures muscle contractions and helps to eliminate the bile into the cystic duct. The final and outer layer is a thick layer of connective tissue containing large blood vessels, lymphatics and nerves. The outer layer of the gallbladder can be either serosa or adventitia. The gallbladder wall that has direct contact with the liver contains adventitia, while the gallbladder wall that is covered by the peritoneum contains serosa made of connective tissue and mesothelium (epithelial layer of the peritoneum).

The extrahepatic bile ducts consist of mucosa, muscular layer (not all ducts have it) and adventitia.. The mucosal layer is similar to that of the gallbladder, and the epithelium is formed by a single layer of columnar cells. Lamina propria contains connective tissue with fibroblasts, small vessels and collagen fibers. The muscular layer is present along the common bile duct and at the junction of the gallbladder and cystic duct. The outer fibrous layer contains connective and adipose tissue, vessels and nerves.

Neurovascular supply of gallbladder and biliary tree

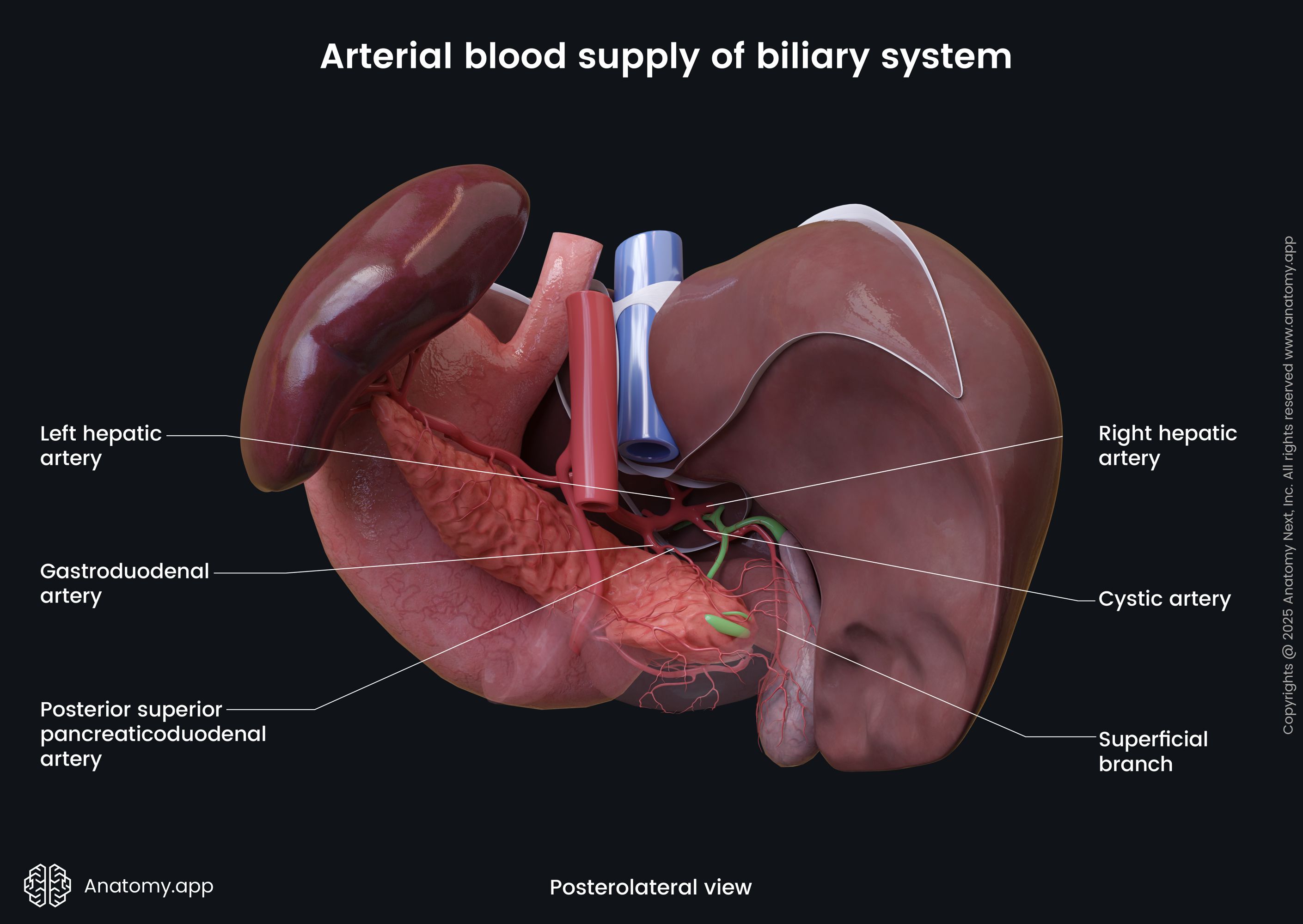

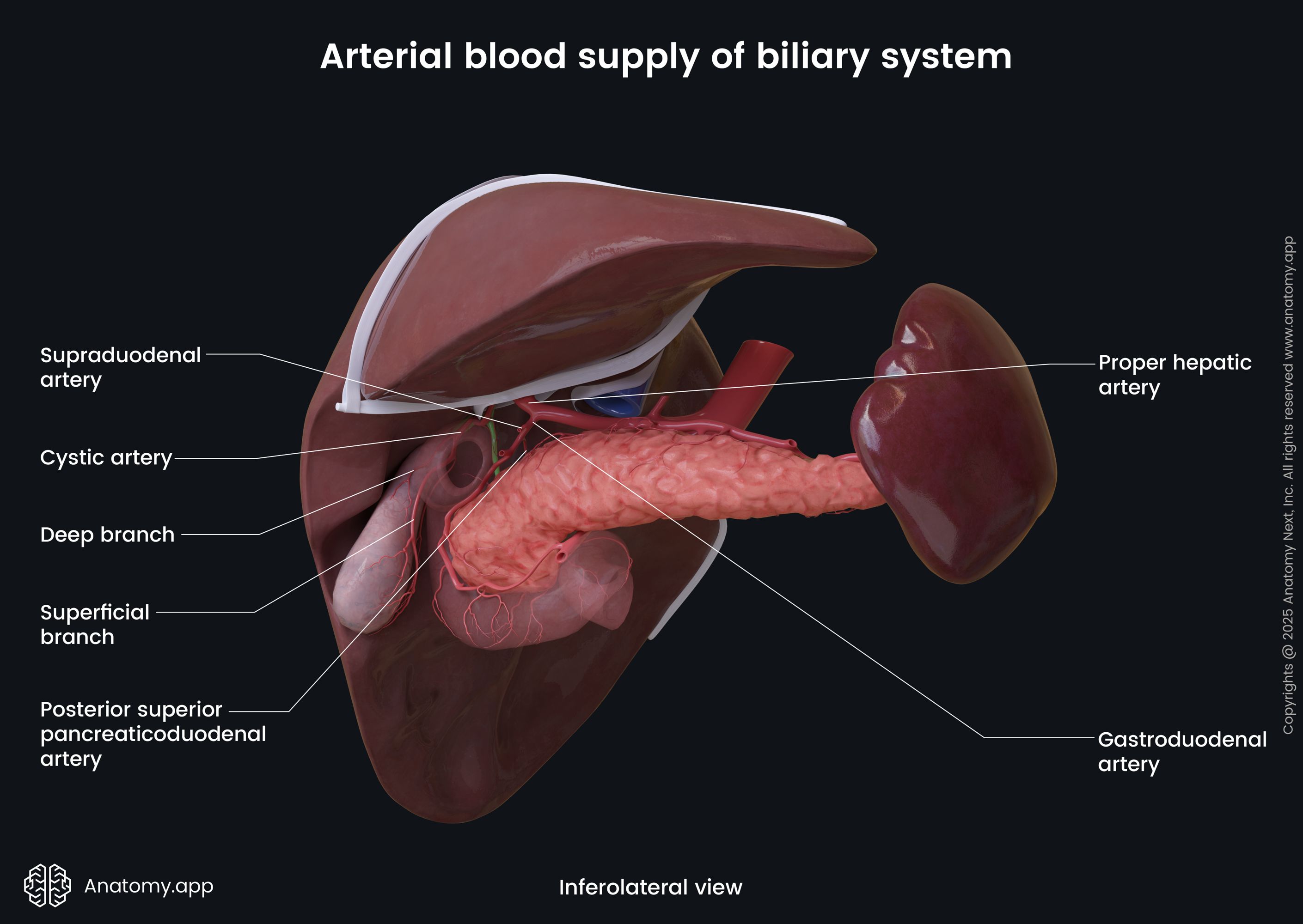

Arterial blood supply

Arterial blood flow to the gallbladder is typically ensured by the cystic artery. It usually originates from the right hepatic artery and passes posterolaterally to the common hepatic duct. After reaching the neck of the gallbladder, it divides into superficial and deep branches. Both branches anastomose with each other at the level of the body and fundus of the gallbladder. The superficial branch supplies inferior aspects of the body, while the deep branch provides arterial blood supply to the superior parts of the body. Additionally, the cystic artery gives off two to four small branches (Calot’s arteries) supplying the extrahepatic bile ducts - common hepatic duct, cystic duct and proximal common bile duct.

The common bile duct receives arterial blood supply from several small ascending and descending arteries along its length. Descending arteries are mainly branches of the right hepatic artery and cystic artery. Ascending branches arise from the gastroduodenal, posterior superior pancreaticoduodenal, supraduodenal and retroportal arteries.

The extrahepatic part of the right and left hepatic ducts is supplied by branches of the right and left hepatic arteries, respectively, forming a plexus near the hepatic hilum. The intrahepatic biliary ducts are supplied by the segmental branches of the hepatic arteries and intrahepatic arteries that form a capillary network around the ducts.

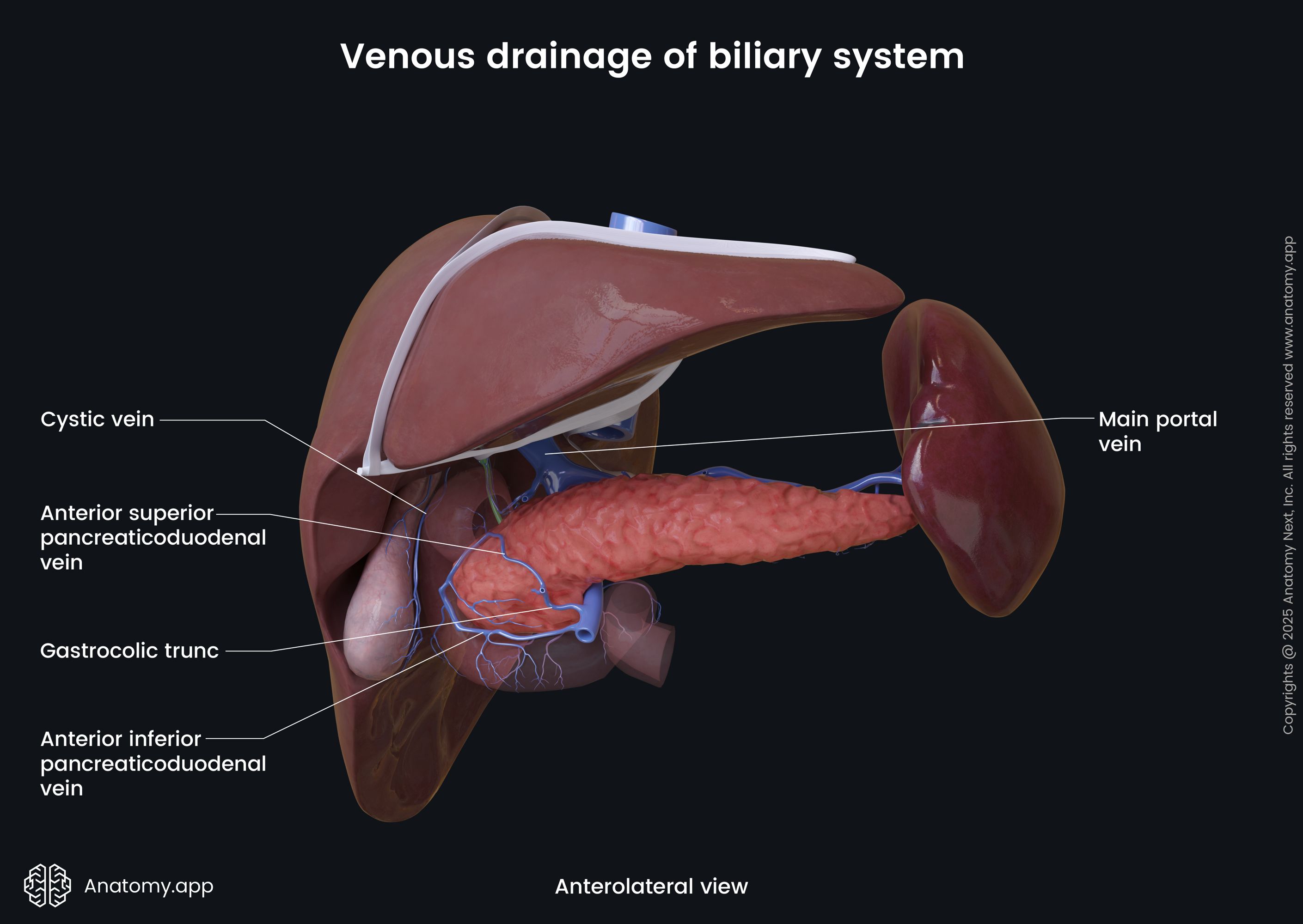

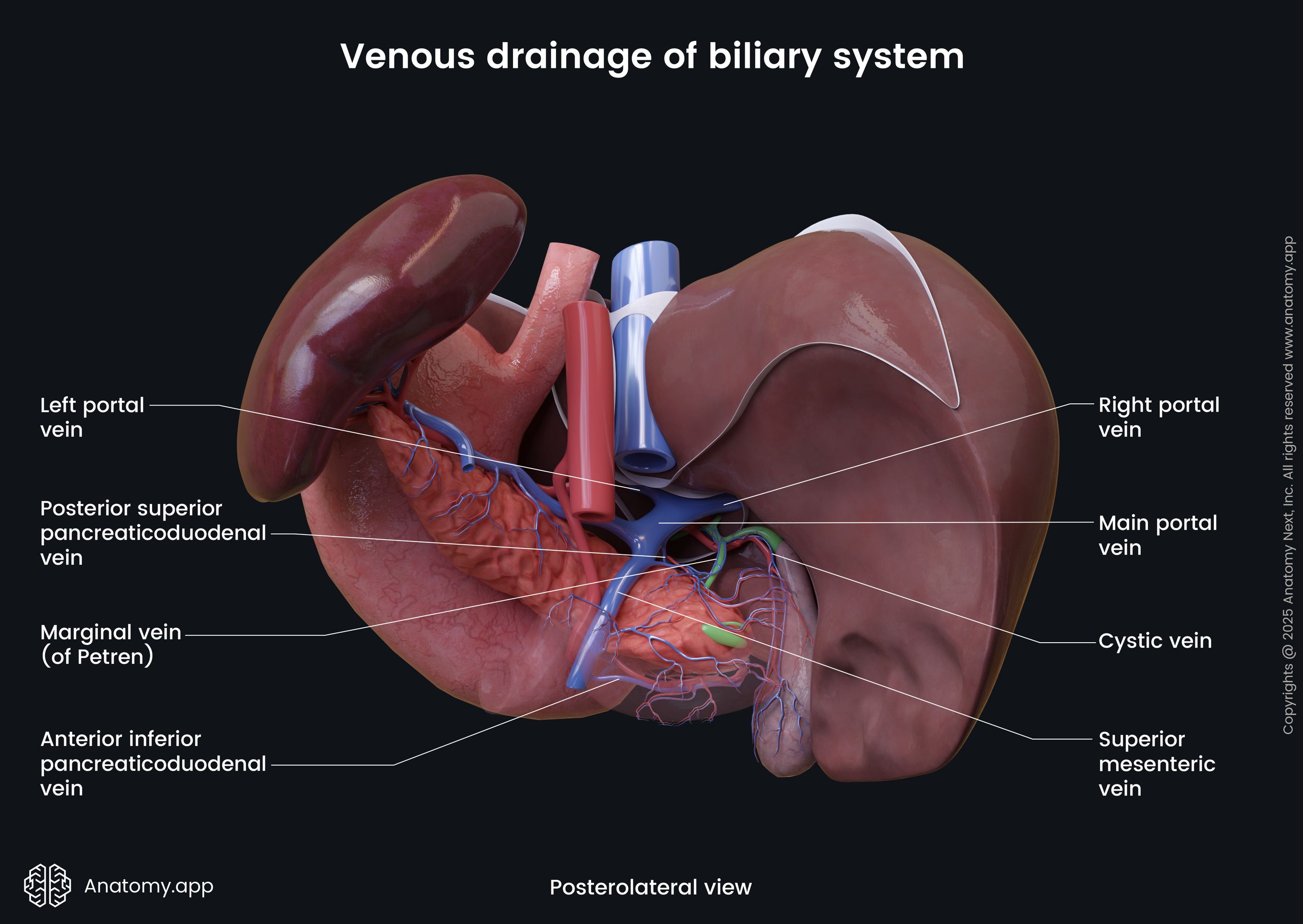

Venous drainage

The venous drainage from the gallbladder occurs via multiple small veins that drain into the segmental portal veins. Venous plexuses around the common hepatic duct and common bile duct drain through the marginal veins into the posterior superior pancreaticoduodenal vein, right gastric vein, superior mesenteric vein (inferiorly) and hilar venous plexus (superiorly).

Lymphatic drainage

The biliary tract contains several lymphatic drainage systems collecting lymph from the gallbladder and biliary ducts. From the gallbladder, lymph drains via two routes - to either the cystic lymph nodes above the cystic duct or the pericholedochal lymph nodes along the common bile duct. From the cystic nodes, lymph is drained to the pericholedochal nodes, from which it is further directly carried to the interaortocaval nodes. Also, the lymph can reach mentioned nodes via the posterosuperior pancreaticoduodenal or retroportal lymph nodes. The retroportal nodes can also drain into the interaortocaval nodes via the coeliac nodes, while the posterosuperior pancreaticoduodenal nodes can drain into the interaortocaval nodes via the superior mesenteric nodes. And finally, from the interaortocaval nodes, lymph reaches the thoracic duct. The lymph vessels from the common hepatic and common bile ducts also drain through the hepatic nodes of the porta hepatis into the coeliac nodes or directly into the superior mesenteric and posterosuperior pancreaticoduodenal nodes.

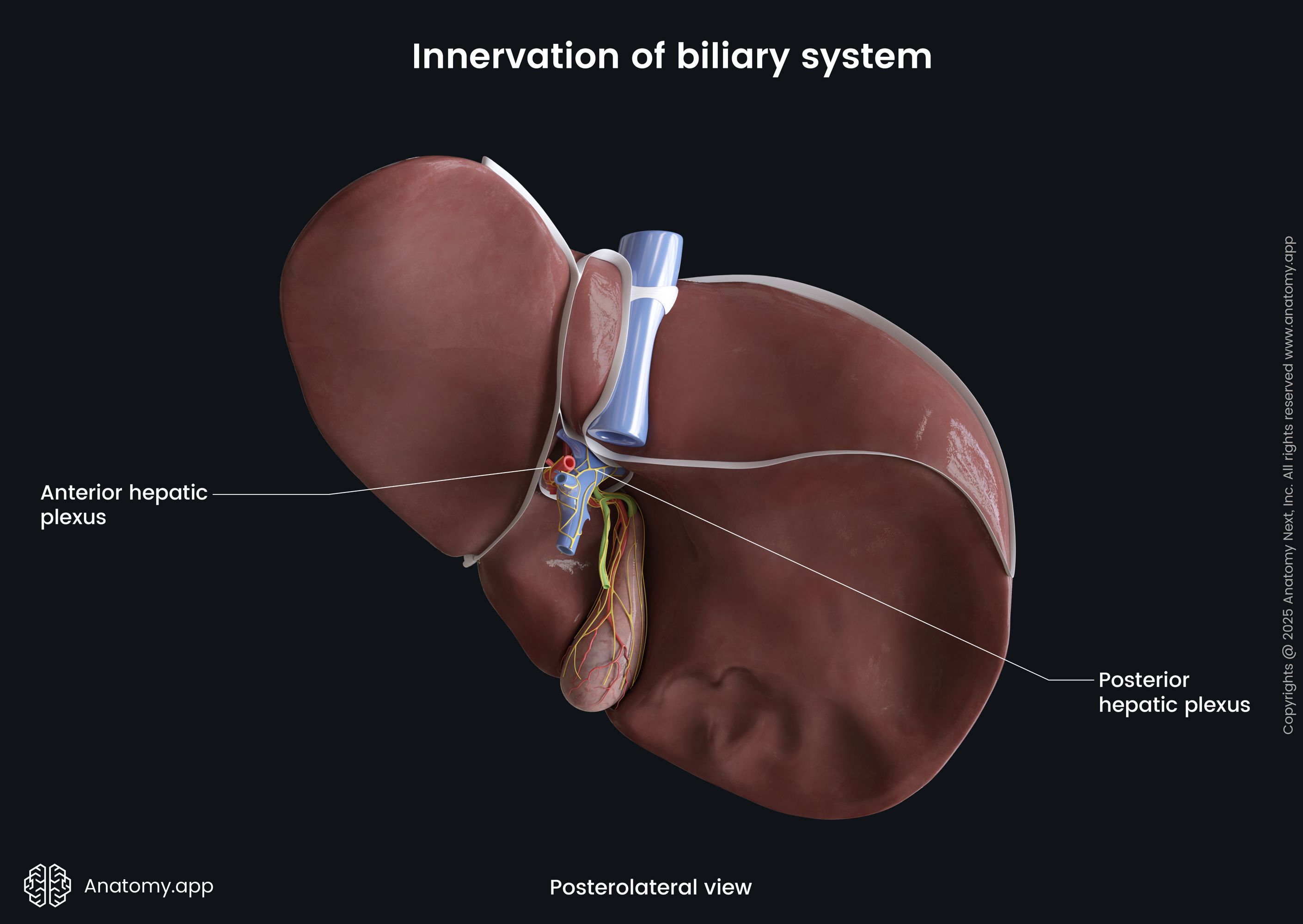

Innervation

The gallbladder and biliary tree receive parasympathetic, sympathetic and sensory innervation. The parasympathetic innervation happens through the vagus nerve (CN X). The fibers of the vagus nerve innervate the gallbladder, common bile duct and hepatopancreatic ampulla either directly (usually branches of the left vagus) or through the hepatic plexuses. The sympathetic innervation is mainly provided by the sympathetic nerves (T7 - T9) that reach the liver via the coeliac plexus. The sensory innervation comes from the right phrenic nerve. The smooth muscle cells contract in response to the hormone cholecystokinin and vagal stimulation. In contrast, muscles relax in response to sympathetic stimulation.

Overall, the liver contains two plexuses - anterior and posterior hepatic plexuses - that not only supply the liver but also the biliary tract. Both plexuses communicate with each other. The anterior hepatic plexus surrounds the hepatic artery, while the posterior is located around the extrahepatic bile ducts and portal vein. The anterior plexus is formed by the left vagus nerve (CN X) and nerves from the right and left coeliac ganglia. It innervates the gallbladder, cystic duct and segment of the common bile duct within the pancreas. In contrast, the posterior hepatic plexus receives nerve fibers from the right vagus nerve (CN X) and right coeliac ganglion. Most of these nerves enter the liver and supply the intrahepatic ducts.

Regulation of bile secretion and release

The release of bile from the gallbladder happens under neuroendocrine control. After a meal, neuroendocrine cells of the proximal small intestine (mainly duodenum) secrete a hormone called cholecystokinin (CCK) as a response to fatty acid levels within the small intestine. Smooth muscle cells of the gallbladder wall contain CCK receptors. The muscle cells that bind with CCK cause contractions of the gallbladder body and relaxation of its neck. This process allows the release of the bile into the cystic duct and further into the common bile duct. Once the pressure of the bile within the extrahepatic biliary tree reaches a certain level, the sphincter of Oddi relaxes, and bile is released into the descending part of the duodenum.

Besides the hormonal regulation, increased contractions of the gallbladder and relaxation of the sphincter of Oddi after a meal are also provided by parasympathetic stimuli coming from the vagus nerve (CN X). Bile secretion and release is a cycle-like process as the presence of acid chyme (thick semi-fluid mass formed by digestive fluids and partly digested food) in the duodenum causes the release of a hormone called secretin from the duodenal cells. Secretin and vagus nerve (CN X) stimulates increased bile formation. Therefore, the bile is transported from the gallbladder and directly from the liver.

Biliary tract disorders

The most common disorders of the gallbladder and the biliary tree are gallstones (also called cholelithiasis) and cholecystitis. Gallstones are solid deposits of either bile pigment bilirubin (pigment stones) or cholesterol (cholesterol stones). They are found in around 10% of the population over 40, more commonly in women. Gallstones are usually asymptomatic. However, gallstones may become trapped in the neck of the gallbladder or inside the extrahepatic biliary duct. The gallbladder may become enlarged due to the obstruction and impaired emptying. In this case, the muscle contractions of the gallbladder produce a severe pain attack called biliary colic or gallbladder attack. The pain can last only a few minutes, but it can be as long as a few hours.

The treatment of gallstones depends on the symptoms, their severity, risk of complications and how symptoms affect the patient’s daily life. Usually, only active monitoring and no specific treatment is required for asymptomatic gallstones. Treatment of symptomatic gallstones includes painkillers and a healthy diet. Severe cases and frequent episodes of biliary colic may require cholecystectomy - surgical removal of the gallbladder.

Cholecystitis is an inflammation of the gallbladder, most commonly occurring after the obstruction of the cystic duct by a gallstone. It can be sudden (acute) or can continue over time (chronic). Cholecystitis usually presents with severe pain in the right upper abdominal quadrant, and nausea, vomiting, jaundice and fever are often present. The treatment typically requires antibiotics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Sometimes cholecystectomy is necessary as a treatment method.

References:

- Bibbo, M., & Wilbur, D. (2014). Comprehensive Cytopathology E-Book. Elsevier Gezondheidszorg.

- Brennan, P. P., Standring, S., & Wiseman, S. (2020). Gray’s Surgical Anatomy (1st ed.). Elsevier.

- Drake, R., Vogl, W., & Mitchell, A. (2019). Gray’s Anatomy for Students: With Student Consult Online Access (4th ed.). Elsevier.

- Gray, H., & Carter, H. (2021). Gray’s Anatomy (Leatherbound Classics) (Leatherbound Classic Collection) by F.R.S. Henry Gray (2011) Leather Bound (2010th Edition). Barnes & Noble.