- Anatomical terminology

- Skeletal system

- Joints

- Muscles

- Heart

- Blood vessels

- Lymphatic system

- Nervous system

- Respiratory system

- Digestive system

- Urinary system

- Female reproductive system

- Male reproductive system

- Endocrine glands

- Eye

- Ear

Stomach

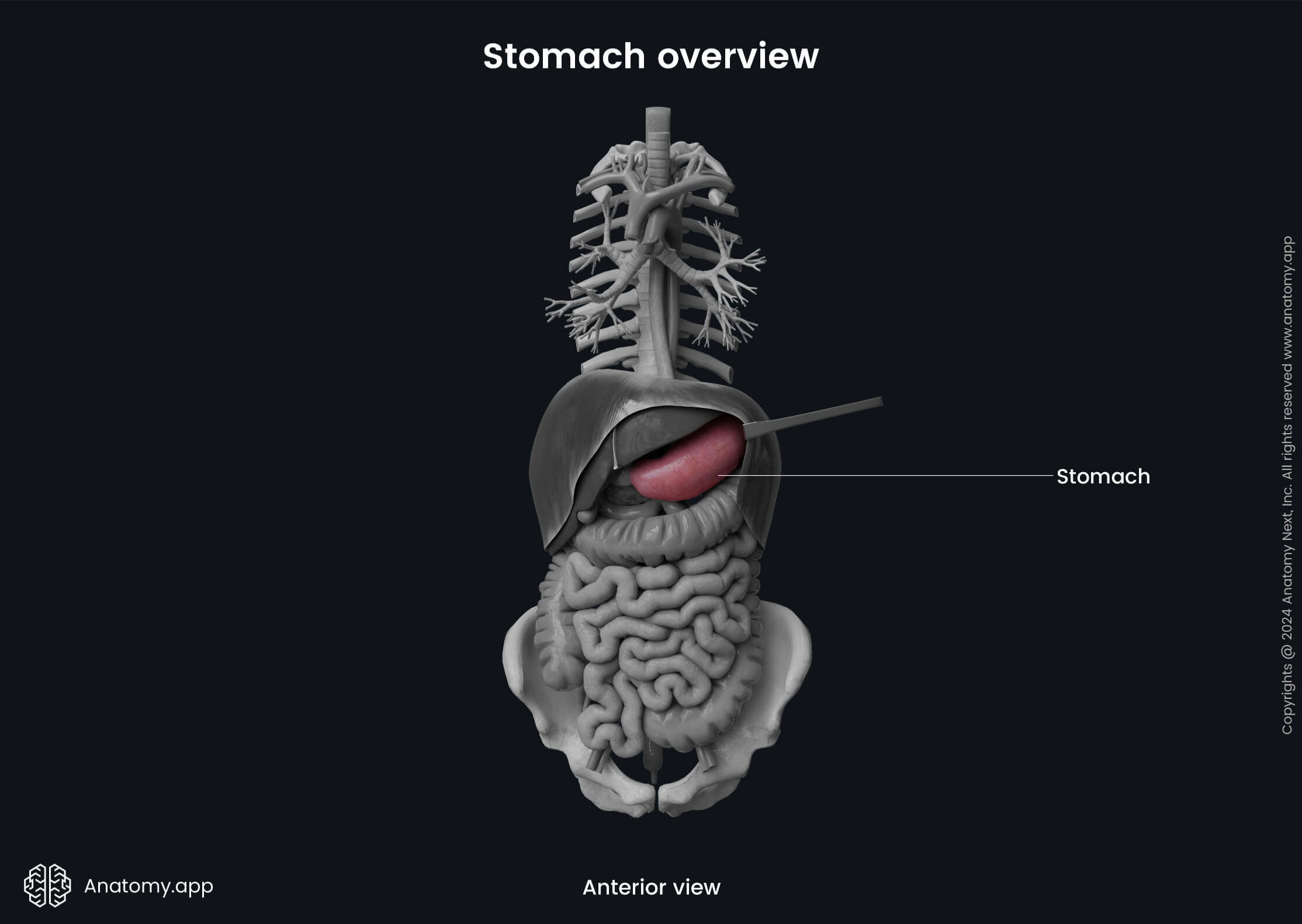

The stomach (Latin: gaster s. ventriculus s. stomachus) is a muscular, expandable "J" shaped organ and the most dilated part of the gastrointestinal tract. It is located in the abdominal cavity inferior to the left dome of the diaphragm, connected to the esophagus and duodenum. The stomach provides chemical and mechanical food procession, absorption, and secretion of various substances.

Stomach anatomy

The stomach is located in the upper region of the abdomen, left from the midline. Around three-fourths of the stomach is located in the left hypochondriac region. The remaining one-fourth can be found in the epigastric region. The stomach is an intraperitoneal organ, and the peritoneum connects it with other organs.

Openings of stomach

The stomach has two openings:

- Cardiac opening (orifice) - between the superiorly situated esophagus and the stomach, situated at the level of the body of the eleventh thoracic vertebra (T11).

- Pyloric opening (orifice) - connects the stomach with the duodenum and is located at the level of the first lumbar vertebra (L1).

Stomach curvatures and surfaces

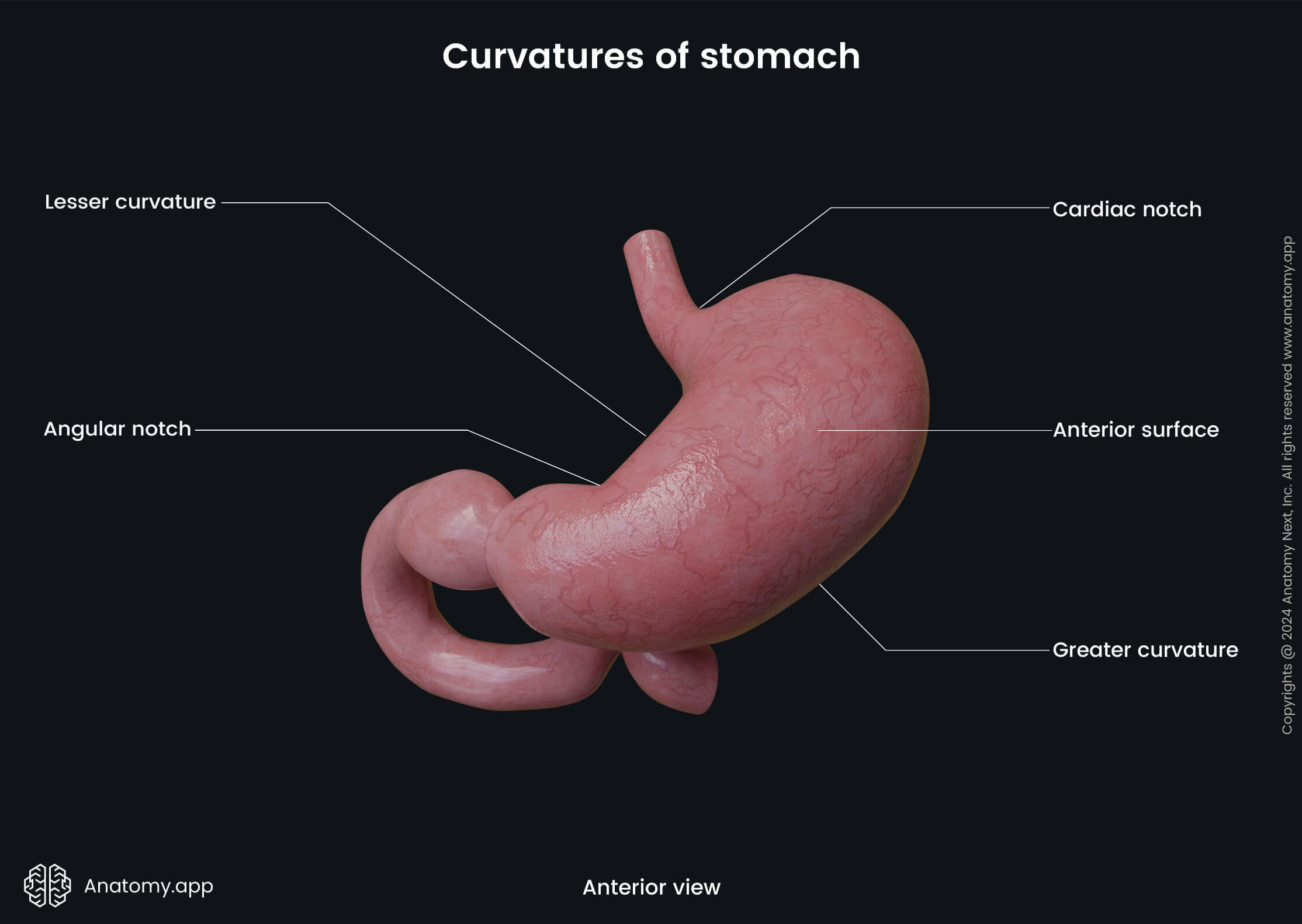

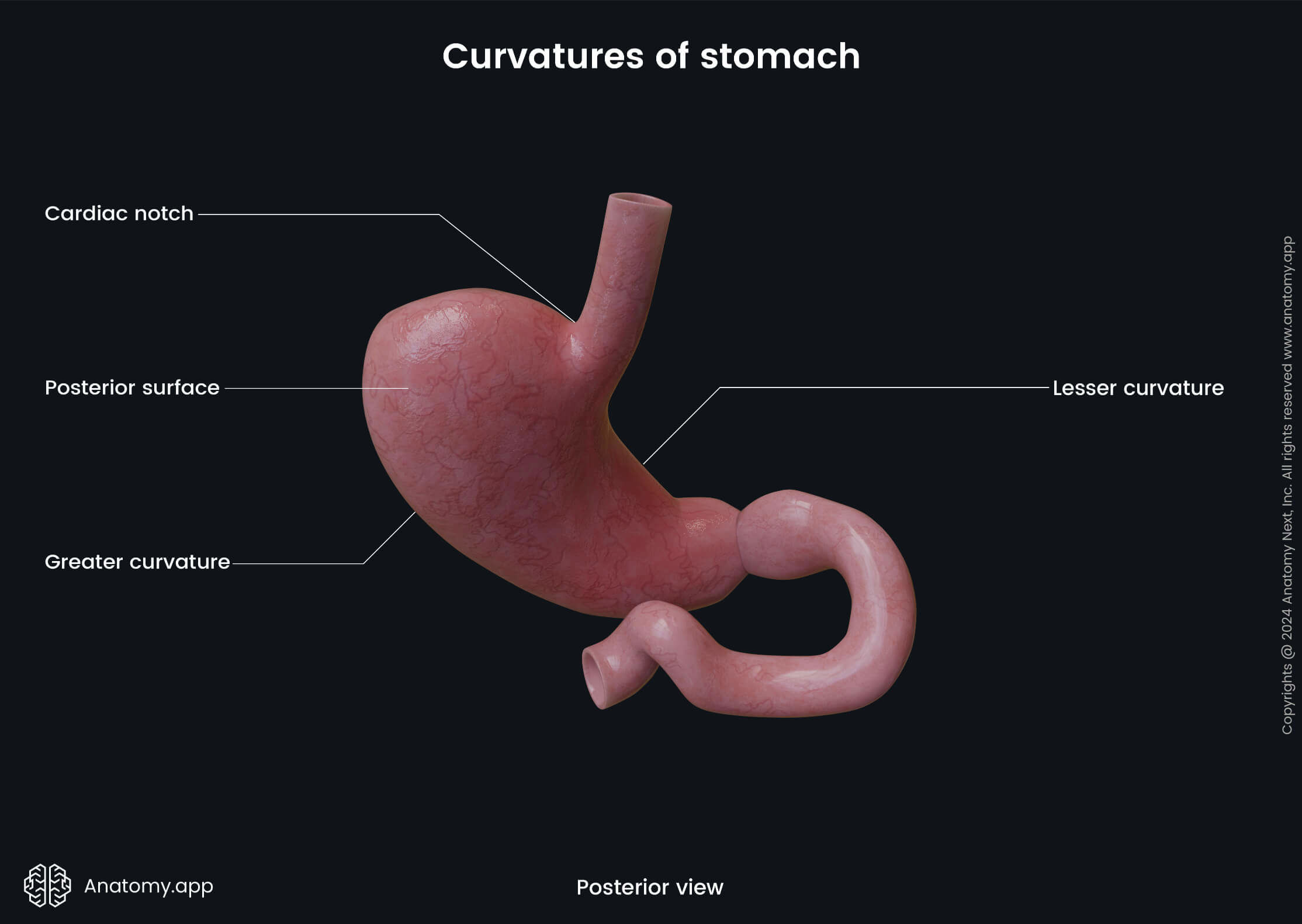

The stomach has two curved borders or curvatures:

- Lesser curvature - shorter, concave, and located more on the right side; between the body and pyloric parts of the stomach in the lesser curvature is the angular incisure, also known as the angular notch; it is the most inferior part of the lesser curvature;

- Greater curvature - located more on the left side, it is longer and convex; between the final part of the esophagus and the start point of the greater curvature (in the fundus part) is the cardiac incisure or notch.

The stomach has two surfaces between both curvatures. Anteriorly between the lesser and greater curvatures is the anterior surface, while posteriorly - the posterior surface.

Stomach parts

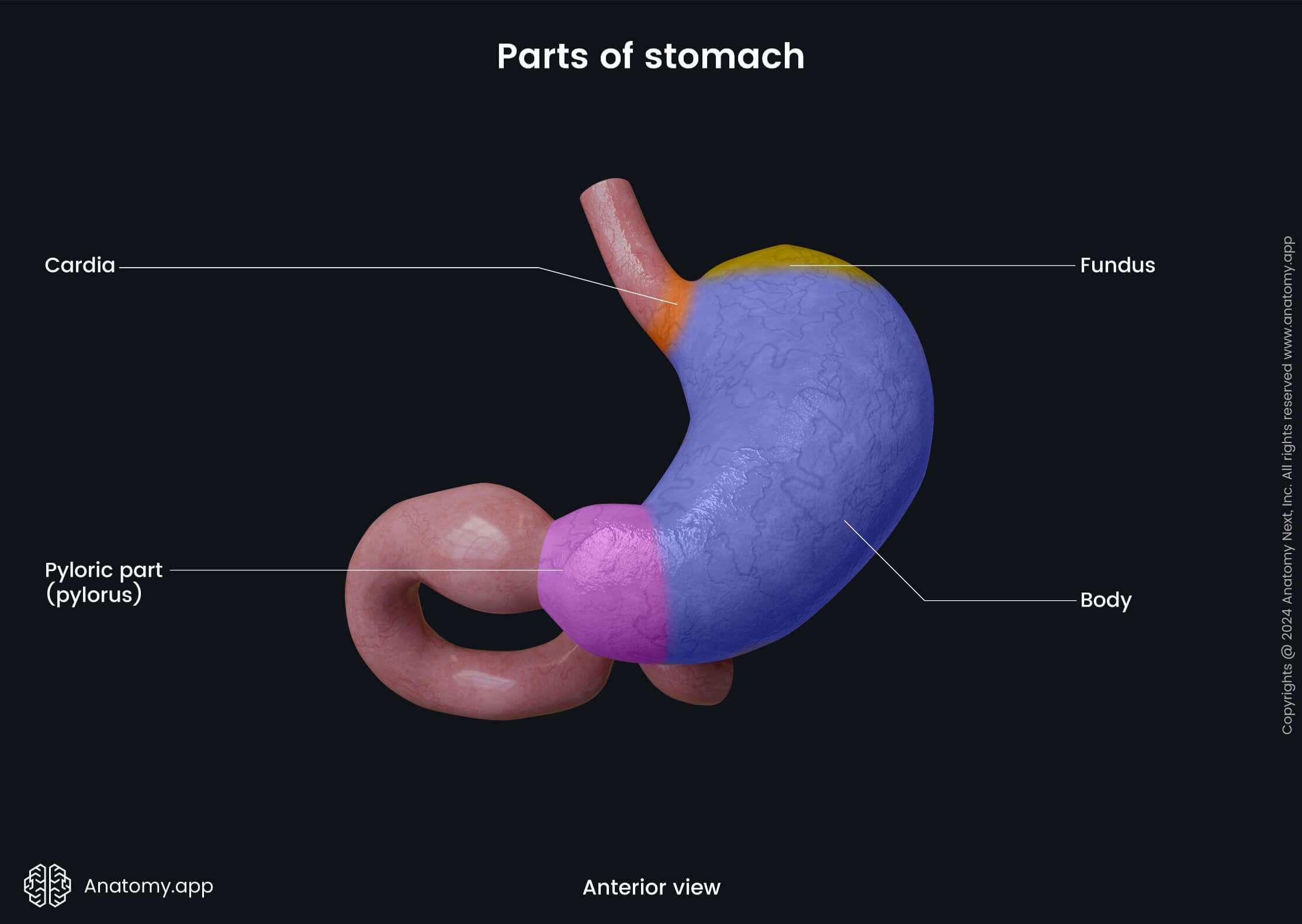

The stomach has four parts:

- Cardiac part (cardia)

- Fundus

- Body

- Pyloric part (pylorus)

The cardiac part, also known as the cardia, is small and only a few centimeters wide. It is around the cardiac opening at the eleventh thoracic vertebra (Th11) level. It is the first part of the stomach receiving the food bolus. The fundus is located above and left to the cardiac opening. It is the most upper part and is rounded and dome-shaped.

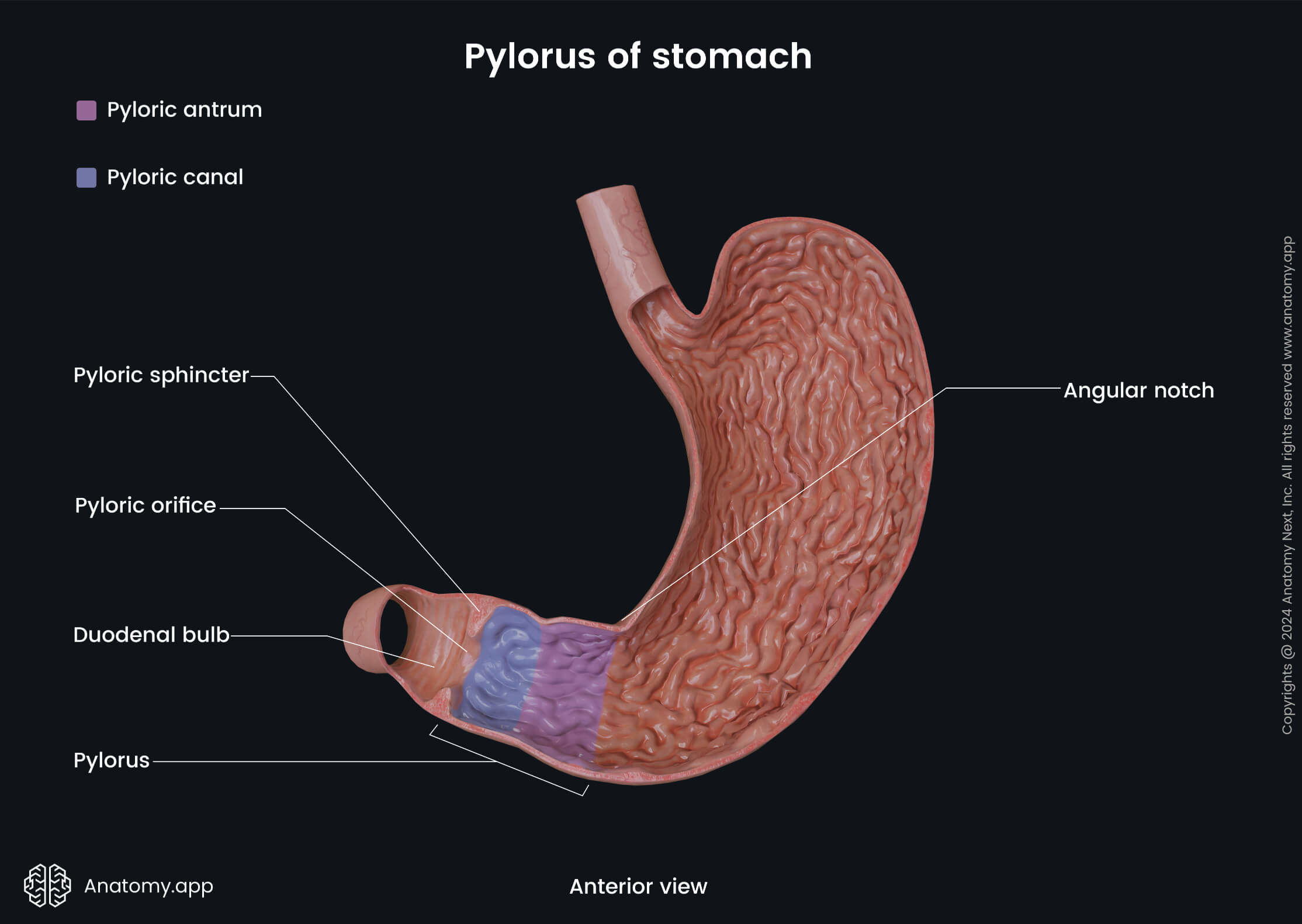

The body is the most significant part of the stomach, located inferior to the fundus, and between the fundus, cardiac part, and pylorus. The pylorus is the most distal part, and it is the continuation of the body part connecting the stomach with the duodenum. It consists of two smaller areas or parts. The first one is wider - it is called the pyloric antrum. The second part is narrower, and it is called the pyloric canal. The pyloric canal ends with the pyloric orifice, which is surrounded by the pyloric sphincter.

Stomach sphincters

Each of the two openings of the stomach contains one sphincter providing the food bolus and chyme movement further to the following parts of the digestive system and at the same time blocking its backflow. These two sphincters connected to the stomach are the inferior esophageal sphincter and the pyloric sphincter.

The inferior esophageal sphincter is also known as the lower sphincter of the esophagus. It is located between the stomach and esophagus left to the midline at the eleventh thoracic vertebra level (T11). The junction place is called the gastroesophageal junction.

The lower sphincter of the esophagus is a physiological sphincter made of longitudinal and circular smooth muscle fibers, the right crura of diaphragmatic muscle, and the fibers from the phrenoesophageal ligament. At the site where the sphincter ir, the gastric mucosa changes into the esophageal mucosa.

The pyloric sphincter is located between the pylorus of the stomach and duodenum. The sphincter controls the passage of the chyme into the duodenum. The pyloric sphincter is an anatomical sphincter and is made of the fibers of the circular muscle layer.

Note: Chyme is a thick semi-fluid mass of partly digested food that is mainly mixed with gastric juice and expelled by the stomach into the duodenum.

Stomach relations and contact areas

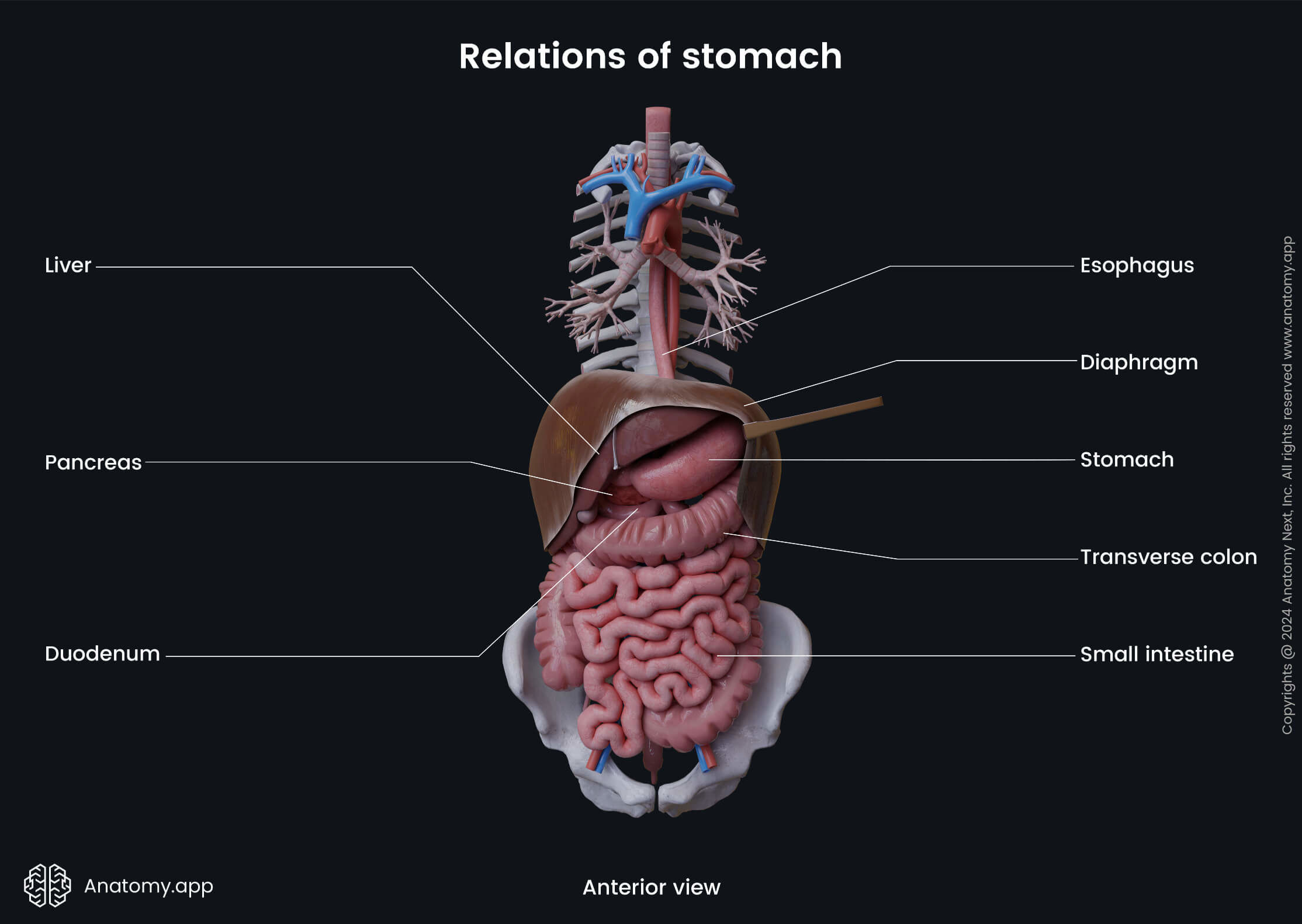

The stomach has connections with various organs. Superiorly the stomach continues with the esophagus and contacts the left dome of the diaphragm. The most distal part of the stomach connects with the duodenum.

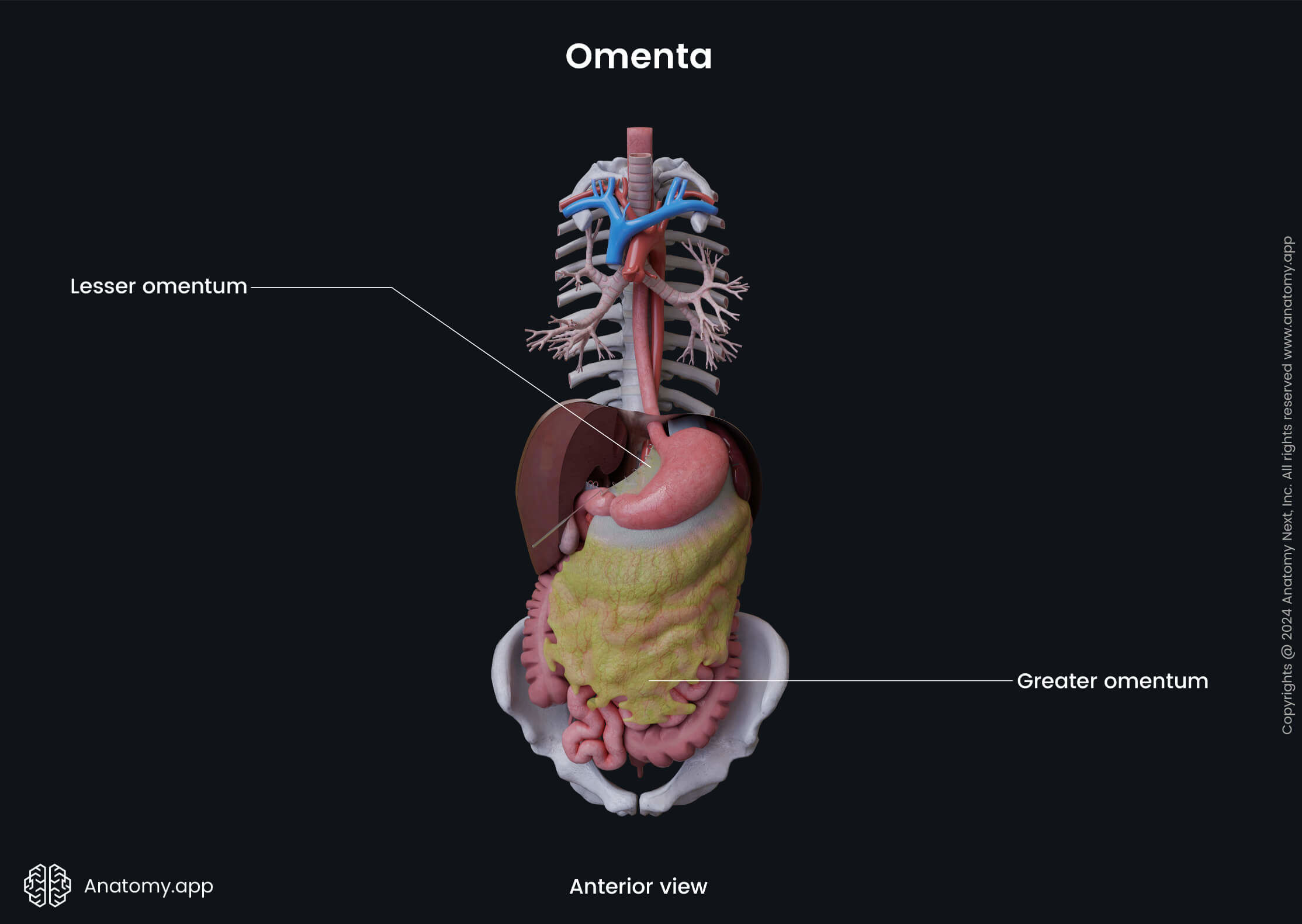

Inferior to the stomach is the transverse mesocolon. The greater omentum contacts with the greater curvature of the stomach as it extends downward from it. The lesser curvature of the stomach is connected to the lesser omentum which extends to the liver.

Anterior surface

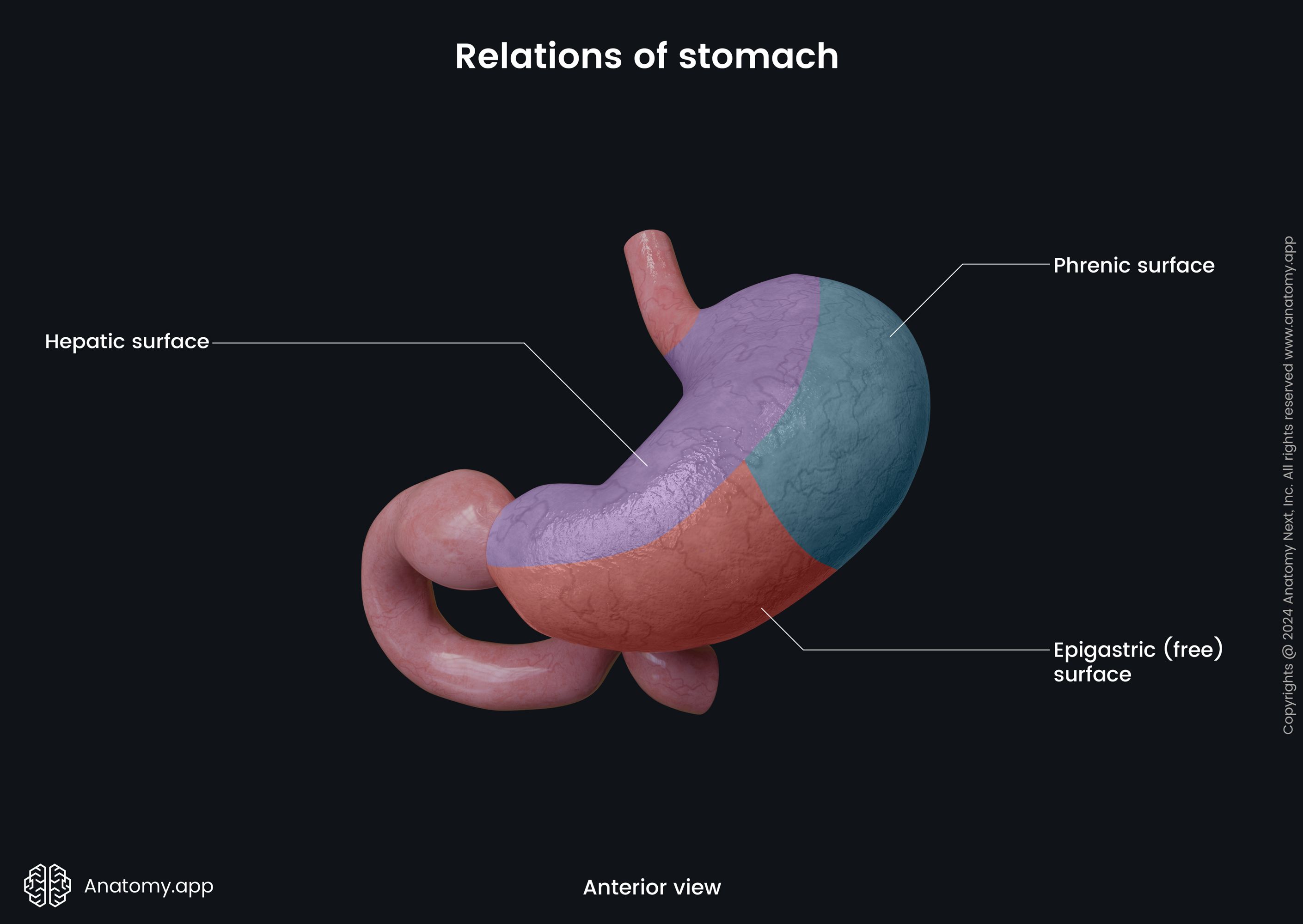

The anterior surface of the stomach is in contact with the left lobe of the liver, diaphragm, and the inner surface of the anterior abdominal wall. The part of the surface that contacts the liver is called the hepatic surface. It is located along the superior part of the lesser curvature from the esophageal opening to the pyloric one. The fundus part and a small area of the body part along the greater curvature is covered by the left dome of the diaphragm. It is called the phrenic surface. The body part in the greater curvature area connects with the abdominal wall. Here, the stomach does not connect with any other internal organ, and this area is known as the epigastric or free surface.

Posterior surface

At the lower part of the posterior surface along the greater curvature lies the transverse colon, and this area of the stomach is known as the colomesocolic surface. The body of the stomach relates to the spleen, and this contact site is known as the splenic surface. The body part also connects with the left kidney and left adrenal gland, and the contact areas are known as the renal surface and suprarenal surface, accordingly.

The pancreatic surface is the site of the body and pyloric parts of the stomach that contact the pancreas. The phrenic area is the place where the stomach contacts the lumbar portion of the diaphragm with its cardiac part, body, and fundus. Also, the splenic artery crosses the posterior surface of the stomach.

Ligaments of stomach

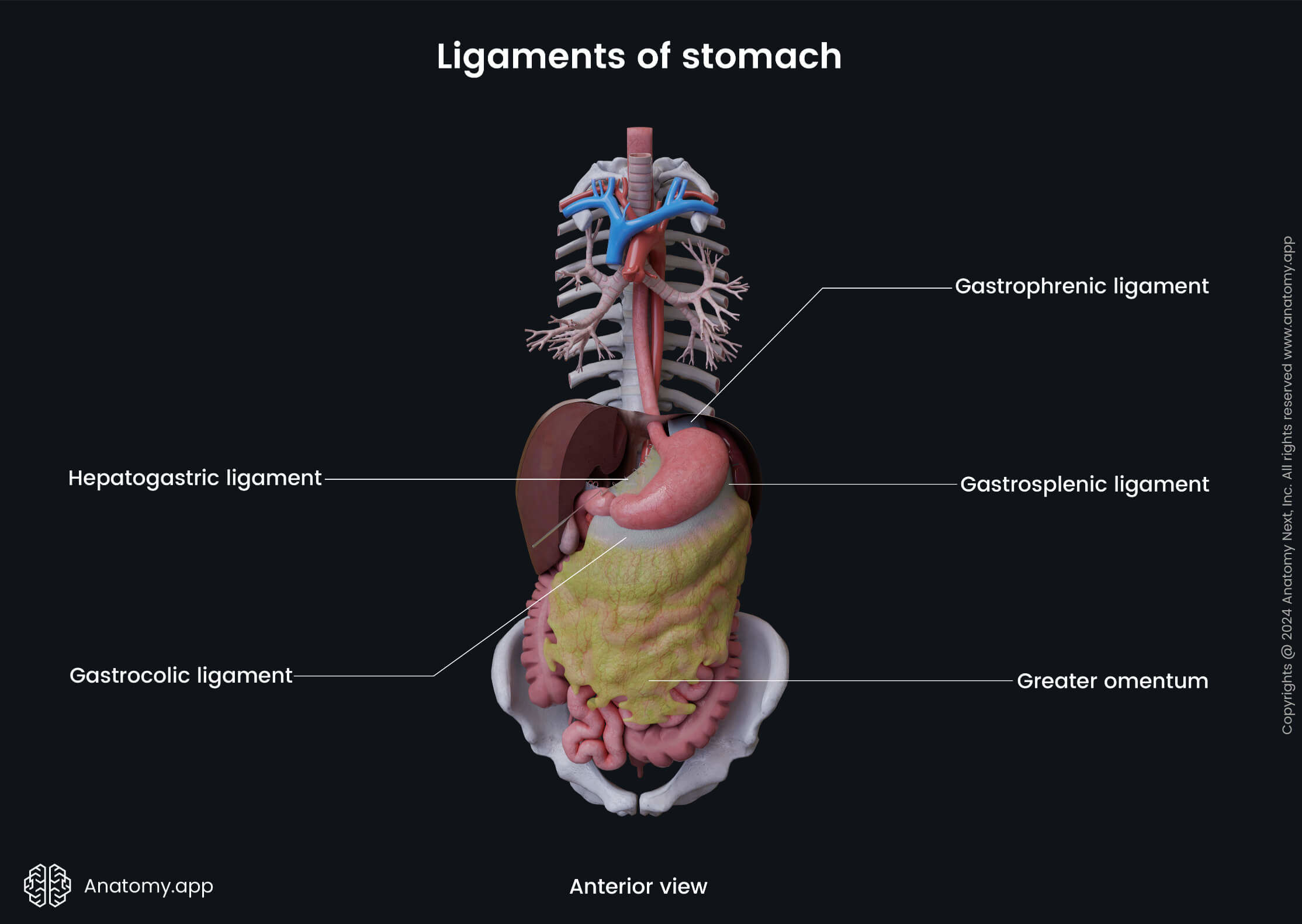

The ligaments of the stomach are fomed by the serosa layer and extend to the nearest organs. They participate in fixating the stomach, and they include the following ligaments:

- Hepatogastric ligament - connects the liver with the stomach, extending from the porta hepatis to the lesser curvature;

- Gastrophrenic ligament - extends from the cardiac notch of the greater curvature to the inferior surface of the diaphragm, connecting the stomach with the diaphragm;

- Gastrosplenic ligament - connects the stomach with the spleen, stretching from the greater curvature to splenic hilum;

- Gastrocolic ligament - stretches from the greater curvature to the anterior surface of the transverse colon, connecting the colon with the stomach. This ligament is a component of the greater omentum.

Stomach histology

The wall of the stomach has four layers:

- Mucosa

- Submucosa

- Muscular layer

- Serosa

Histologically, the stomach is divided into only three parts instead of four as described above, because the body and fundus have the same microscopic characteristics.

Mucosa

The mucosa, together with the submucosa, forms the inner layer of the stomach wall. The mucosa is covered by simple columnar epithelium. The thinnest mucosa lines the cardiac part of the stomach. The mucosa of the stomach contains lymphoid tissue aggregates.

Underneath the epithelium is the lamina propria consisting of connective tissue, blood vessels and lymphatics. Below the lamina propria lies the muscle layer or muscularis mucosa containing smooth muscle fibers. The muscle layer is located between the lamina propria and submucosa. The muscularis mucosa is formed by inner circular and outer longitudinal muscle layers.

Mucosal folds

The mucosa of the stomach is around 0.8 to 1.2 inches (2 - 3 cm) thick and form mucosal folds (or plicas, rugae) going in various directions. In constant overeating, the folds can stay distended even when the stomach is empty.

Along the lesser curvature, the plicas go in the longitudinal direction, forming a passage for food to the most inferior parts of the stomach. This passageway is called the gastric canal.

From the cardiac opening, the mucosal folds go in the radial direction. In the body and fundus parts, they extend in various directions. Next to the pyloric orifice, the mucosa forms a circular structure. It works as a sphincter and, together with the pyloric sphincter muscle, closes the opening.

Mucous cells

The epithelium contains many surface mucous cells producing viscous mucus covering the mucosa of the stomach. Because of its appearance, the mucus is referred to as cloudy or visible mucus. Mucus is very thick and insoluble in water. The mucous cells of the stomach also produce bicarbonates.

The mucus protects the stomach from the destructive effects of the hydrochloric acid (HCl). Also, the mucus decreases the chance of abrasion and injury from food particles during digestion, protecting against chemical and mechanical injuries.

Gastric pits

The surface epithelium contains many small gastric pits or holes and invaginations connected with gastric glands and ensures secretion. The pyloric part has the deepest pits expanding into two-thirds of the epithelium.

Gastric glands and cell types

The mucosa of the stomach contains gastric glands producing mucus, stomach juice, and various endocrine substances and hormones. The stomach contains glands in every anatomical part, and there are three groups of glands depending on the location: gastric glands proper, cardiac, and pyloric glands.

The gastric glands proper are also known as the principal glands, and they can be found in the body and fundus parts of the stomach, while the other two types contain their location in their names. The cardiac glands are found in the cardia, while the pyloric glands are located only in the antrum part of the pylorus.

In general, the principal glands produce gastric juice, but the cardiac and pyloric glands - hormones. During the outer secretion, the gastric juice is released into the stomach cavity, while the hormones are released in the bloodstream.

The gastric juice contains hydrochloric acid, electrolytes, and organic substances. The principal glands produce approximately 68 - 101 ounces (2 - 3 liters) of gastric juice per day. The juice has an acidic pH, usually around 3, but it can vary between 1.5 - 3.5.

All glands are simple tubular, long branched glands with folded end parts. One gastric pit contains many excretory ducts. For example, the gastric gland proper can have 3 to 7 excretory ducts in one hole. The gastric glands contain many parietal and chief cells. In contrast, the cardiac and pyloric glands have a significant amount of mucous cells but decreased amount of parietal and chief cells.

The parietal cells secrete the hydrochloric acid. The gastric chief cells produce pepsinogen and chymosin. In the acidic environment of the stomach, pepsinogen changes into pepsin - an active enzyme that breaks down proteins during digestion. Chymosin (also known as rennin) is a proteolitic enzyme that plays a role in curdling milk in the stomach.

All glands contain endocrine cells such as D and G cells producing gastrin and somatostatin, but the pyloric part's glands contain even more significant amounts. Somatostatin is a hormone that inhibits gastric acid production, while gastrin enhances mucosal growth in the stomach, gastric motility and production of gastric acid.

Submucosa

The submucosa of the stomach is a relatively thick part and contains a significant amount of loose connective tissue. Because of this tissue, the stomach can quickly expand when it is full. The submucosa contains many lymphatic vessels and blood vessels. It houses many nerve fibers, and the Meissner's plexus or submucosal nerve plexus is located in the submucosa. This nerve plexus contains fibers providing the innervation for smooth muscles in muscularis mucosa, blood vessels, and glands.

Muscular layer

The muscular layer is the middle layer, which contains smooth muscle fibers. It has three sublayers - the inner, middle, and outer. The muscle fiber contractions participate in the mechanical food procession by moving, mixing, and crushing the food bolus.

- The inner layer contains oblique muscle fibers. They extend from the left side of the cardiac opening downwards in the anterior and posterior wall, but these fibers do not reach the greater curvature.

- The middle layer is a circular muscle layer. Next to the pyloric opening, the circular fibers become thicker and create the pyloric sphincter which regulates and provides the movement of the stomach content into the duodenum and prevents backflow. It can be up to 0.4 inches (1 cm) thick.

- The outer layer contains longitudinal muscle fibers, and it is called the longitudinal layer. These fibers are primarily located along the greater and lesser curvature. The anterior and posterior walls of the stomach have only a small number of longitudinal fibers.

The muscular layer contains many nerve cells forming a nerve plexus located between the longitudinal and circular layers. This nerve plexus is known as Auerbach's plexus. In contrast to the Meisner's plexus containing only parasympathetic fibers, the Auerbach's plexus also contains sympathetic fibers.

Serosa

The serosa is the outer part of the stomach wall. It covers the stomach from all sides, except the greater and lesser curvatures. It is a formed by the visceral peritoneum. The serosa also forms the ligaments that stretch to the nearest organs and fixes the stomach in its place. The serosa is lined by the mesothelium, which is a single layer of simple squamous epithelium. Underneath it, is loose connective tissue supporting the mesothelium.

Neurovascular supply of stomach

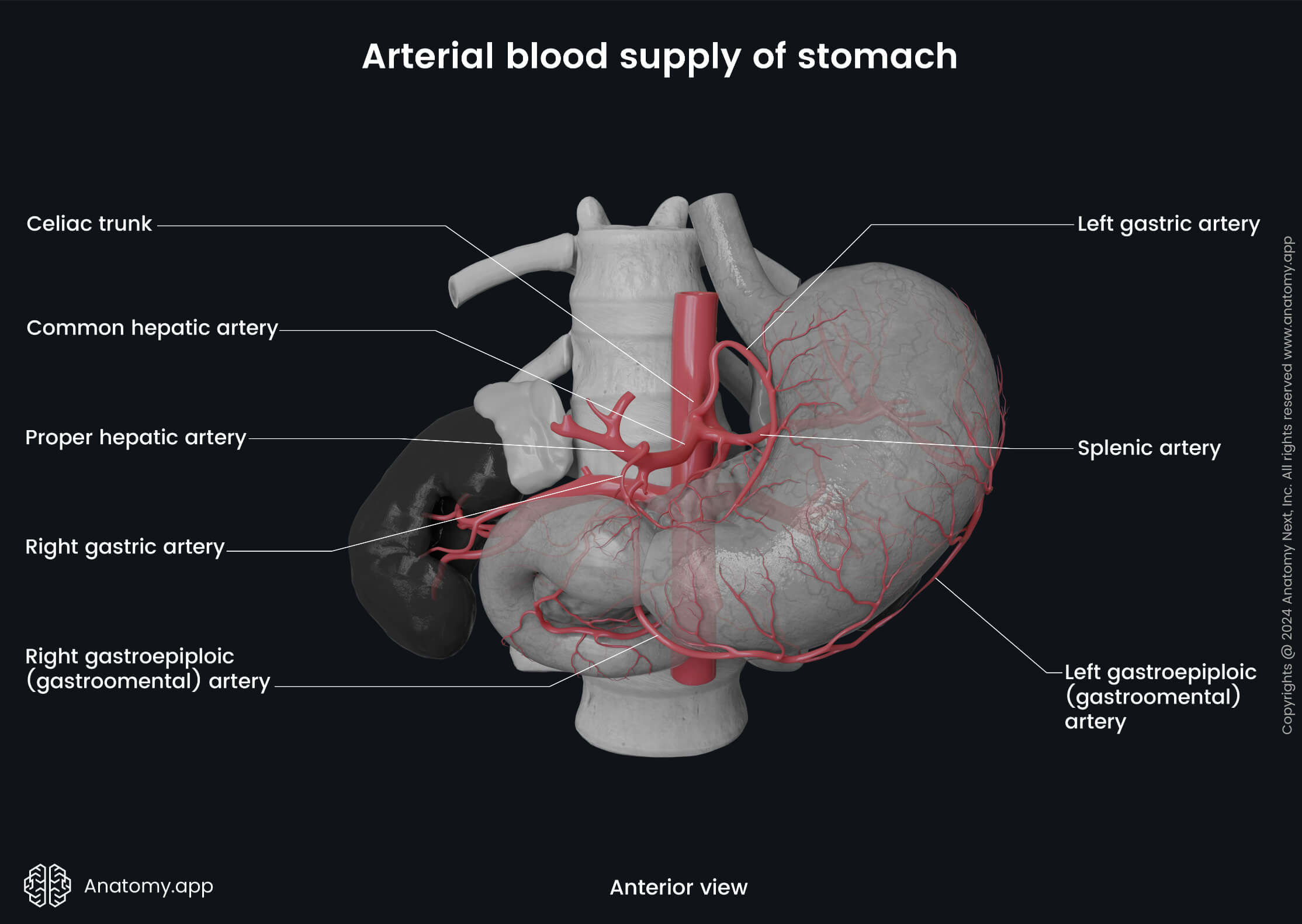

Arterial blood supply

The arterial blood supply of the stomach is mainly provided by the left and right gastric arteries, which pass along the lesser curvature. The left gastric artery is a branch of the celiac trunk. The right gastric artery arises from the common hepatic artery, which is another branch of the celiac trunk.

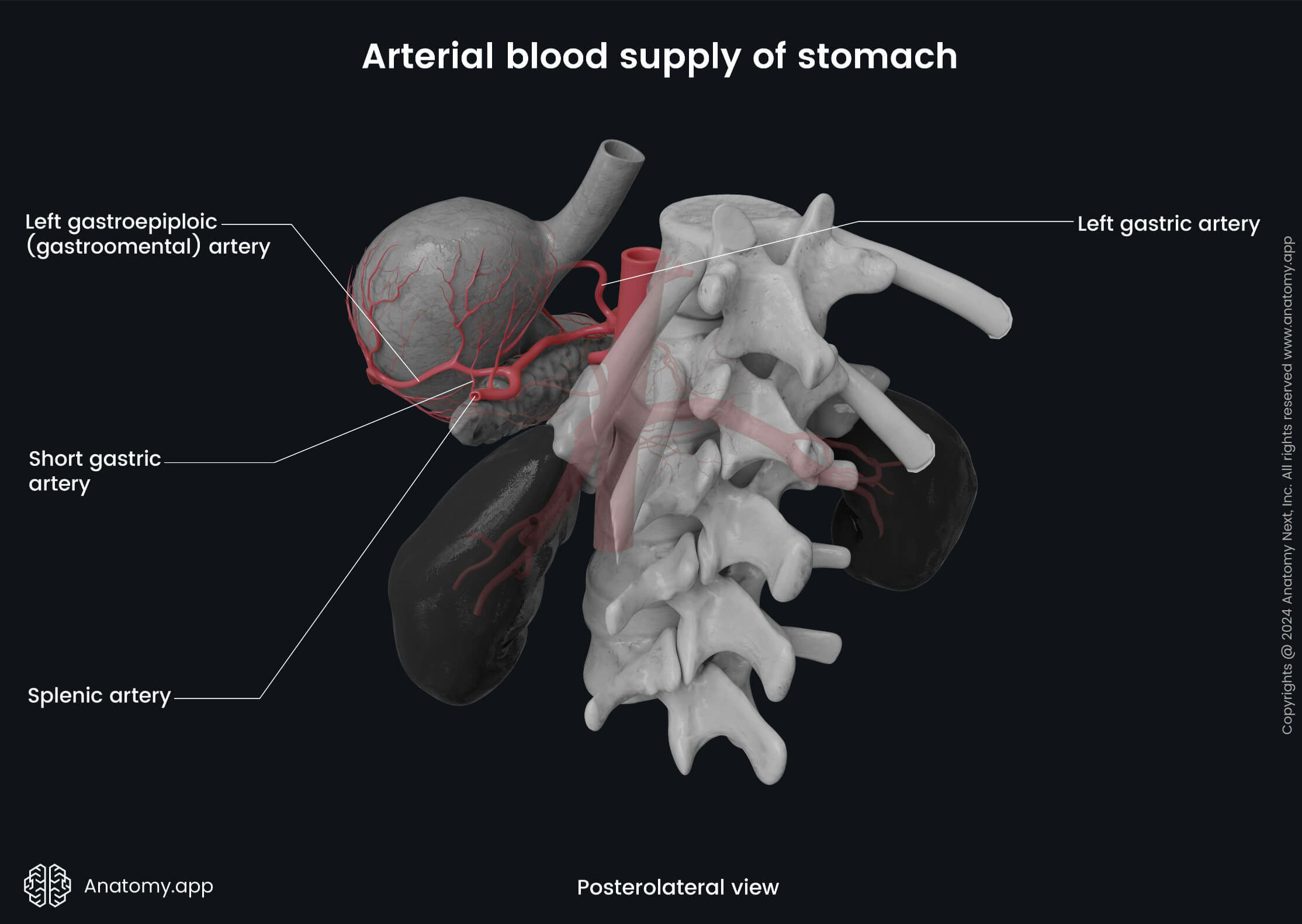

Additional blood supply comes from the left and right gastroomental arteries, which anastomose along the greater curvature. The left one is a branch of the splenic artery, while the right is a terminal branch of the gastroduodenal artery (a branch of the common hepatic artery). The splenic artery also gives off short gastric arteries that supply the fundus part of the stomach.

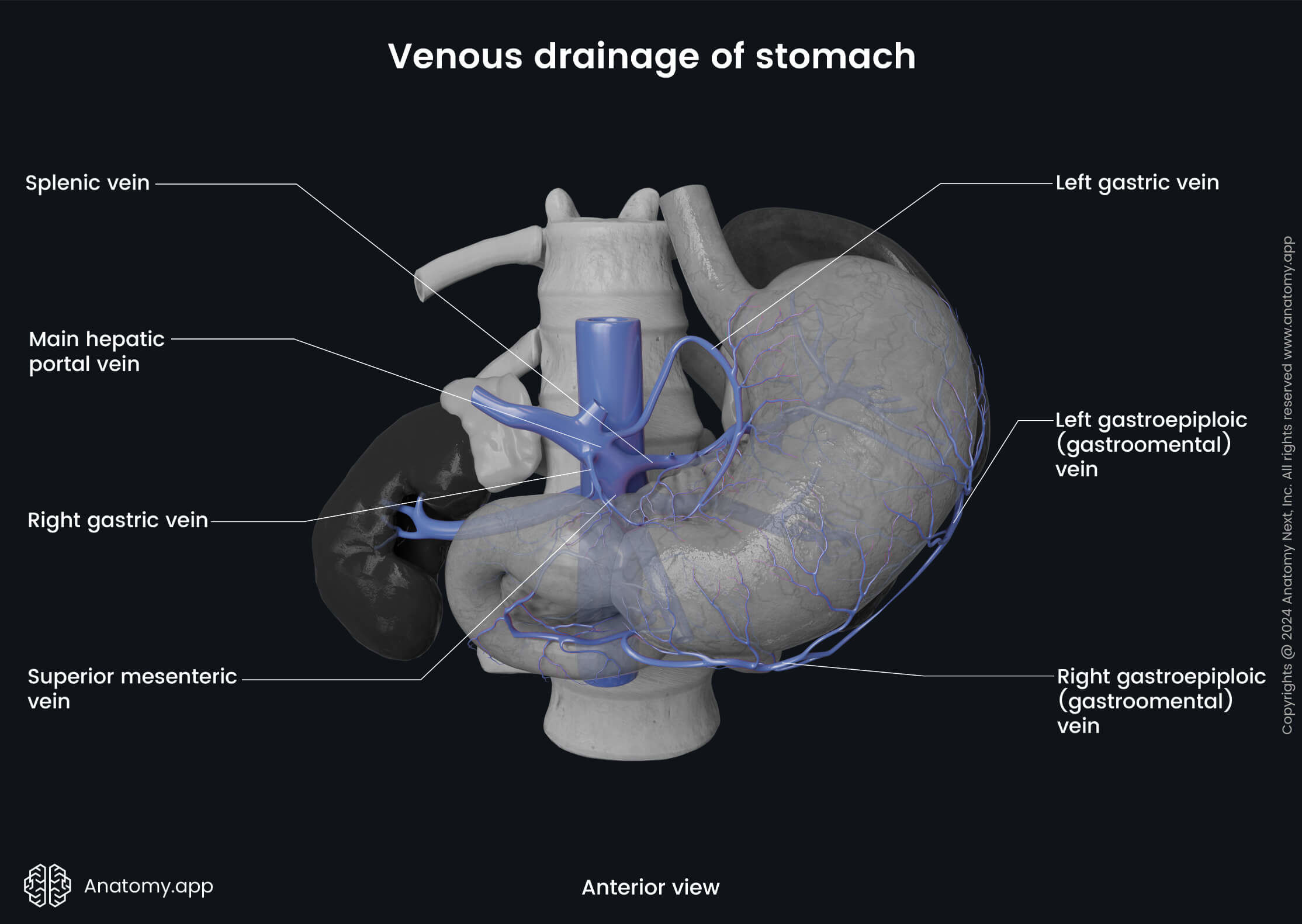

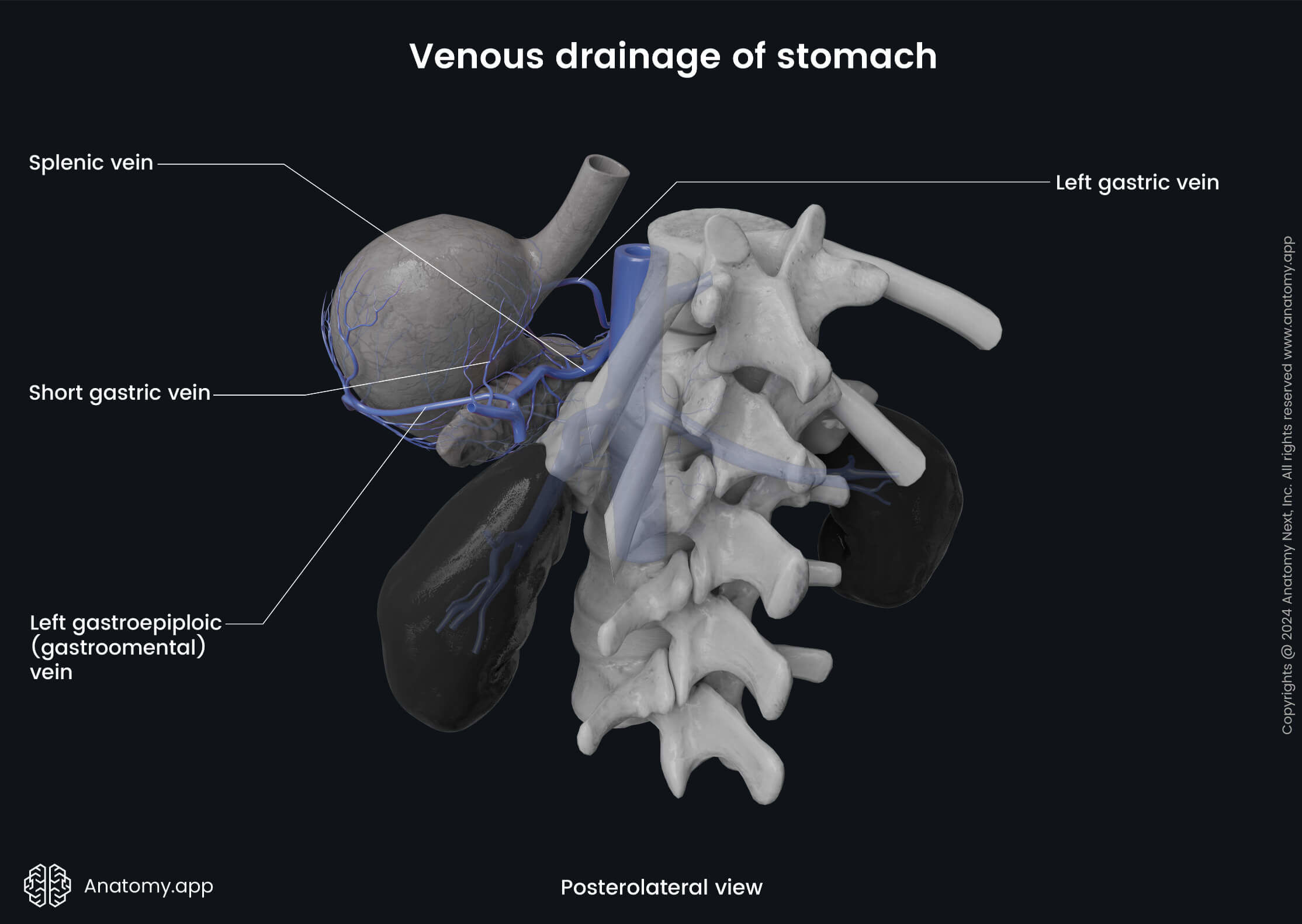

Venous drainage

The venous drainage of the stomach is provided by the portal venous system. The left and right gastric veins collect venous blood from the stomach and drain into the hepatic portal vein. The short gastric and left gastroomental veins drain into splenic vein. The splenic vein carries the blood to the hepatic portal vein. Finally, venous blood is also drained into the superior mesenteric vein via the right gastroomental veins. The superior mesenteric vein carries blood to hepatic portal vein.

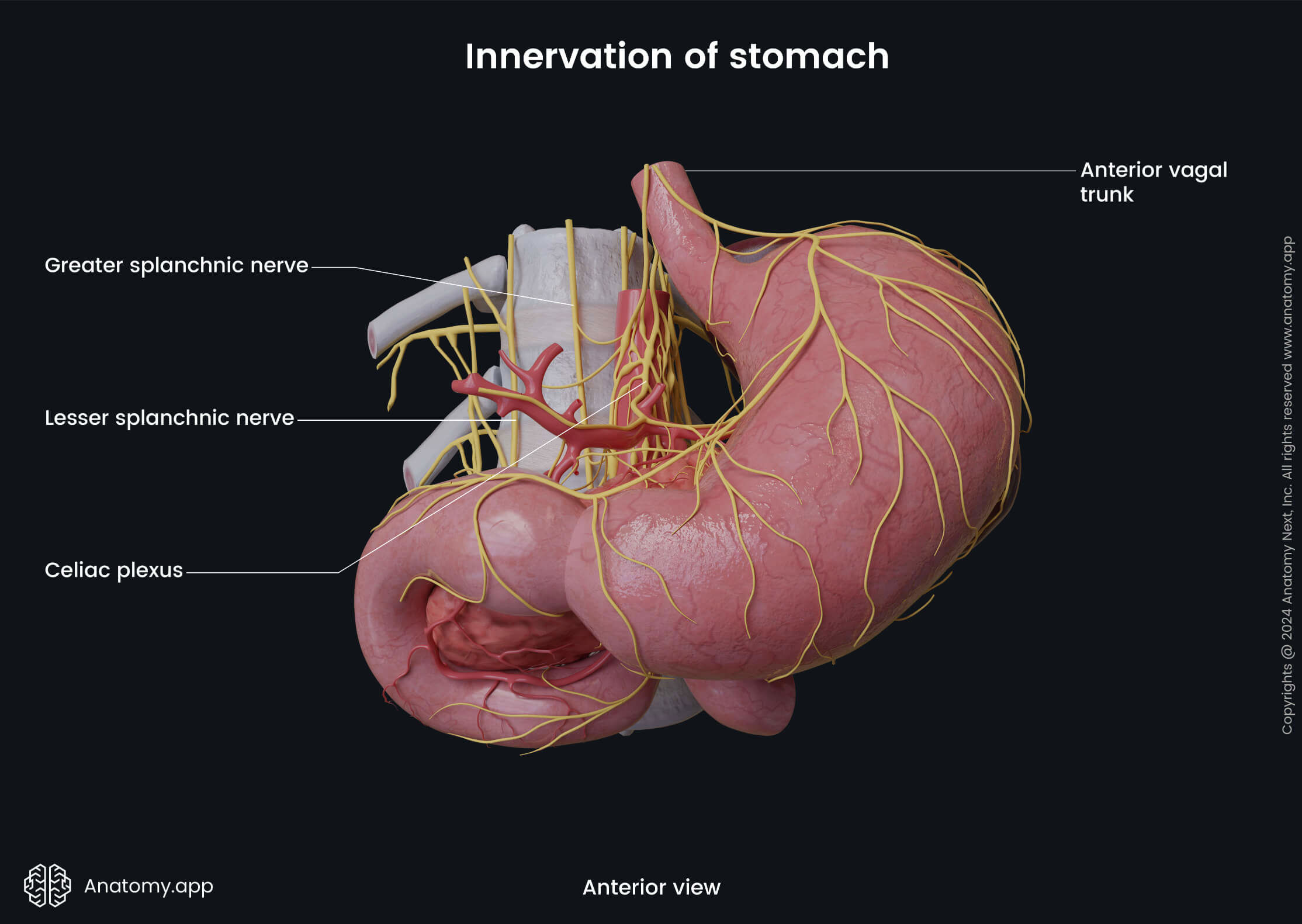

Innervation

The autonomic nervous system innervates the stomach via parasympathetic and sympathetic nerve fibers. Primary, the anterior and posterior vagal trunks provide the parasympathetic innervation of the stomach. Both are branches of the vagus nerve (CN X). The parasympathetic innervation activates secretion and relaxation of the pyloric sphincter during movement of the chyme.

Sympathetic innervation of the stomach is provided by the celiac plexus via the greater splanchnic nerves that originate from the sixth to ninth thoracic spinal nerves (T6 - T9). The sympathetic nervous system inhibits the secretion and motility of the stomach and provides constriction of the pyloric sphincter.

Lymphatic drainage

The lymphatic drainage of the stomach is ensured by the gastric and gastroomental lymph nodes located along the lesser and greater curvatures. Lymph vessels collecting lymph travel together with arteries to the mentioned lymph nodes. Also, the pyloric part of the stomach is drained by the superior and inferior pyloric lymph nodes that further drain to the celiac lymph nodes.

Stomach functions

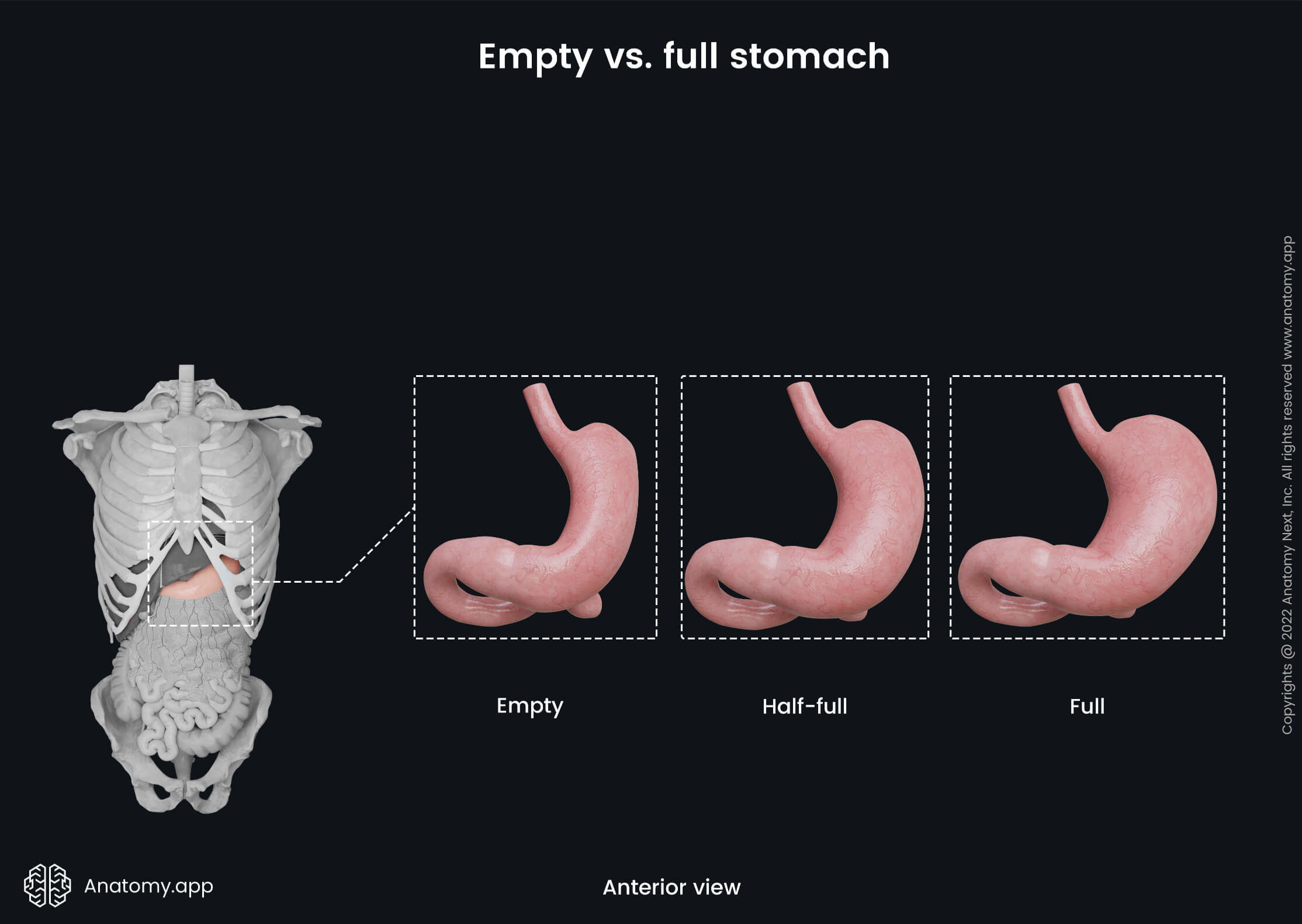

The stomach provides the initial digestion of food and its nutrients, and the food is prepared for the later stages of the digestive process, which takes place in the small intestine. It takes about 2 - 5 hours to empty the stomach depending on various factors such as food type, amount of ingested food, and existing disorders. There are several primary functions of the stomach described below.

- Temporarily stores ingested food and serves as a reservoir for two or more hours, as its volume is 51 - 6 ounces (1.5 - 2 liters) and can even reach 135 ounces (4 liters).

- The stomach is the place where chyme is formed as the stomach provides mechanical food procession and motor function by crushing, grinding, and mixing the food with the gastric juice and the help of peristalsis. The stomach combines and breaks down the food bolus in even smaller particles.

- Besides mechanical food procession, the stomach provides chemical procession. It breaks down the chemical bonds of some nutrients with the help of its secretions - hydrochloric acid and ferments (enzymes), such as pepsinogen (an inactive form of an ferment). In the acidic environment, pepsinogen is converted into an active enzyme called pepsin, which breaks down proteins.

- The stomach produces the intrinsic factor, which is needed to absorb vitamin B12 later in the small intestine.

- The dosing of chyme and its controlled release into the duodenum is regulated by the stomach, as small doses are transferred to the duodenum by every muscle contraction.

- It has a protective function as glands produce mucus that covers the epithelium and protects it from hydrochloric acid.

- Hydrochloric acid not only provides digestion but also protection from various antigens. The higher is the concentration of hydrochloric acid, the fewer microbes are found in the stomach. For example, Vibrio cholera can get killed after 10 to 15 minutes spent in the acid.

- The stomach begins the absorbtion of water, and particular medication (aspirin, water-soluble vitamins), caffeine and ethanol are absorbed in the stomach.

- The stomach induces and provides vomiting mechanism in case of food poisoning or as a reaction to antigens.

References:

- Drake, R., Vogl, W., & Mitchell, A. (2019). Gray’s Anatomy for Students: With Student Consult Online Access (4th ed.). Elsevier.

- Gray, H., & Carter, H. (2021). Gray’s Anatomy (Leatherbound Classics) (Leatherbound Classic Collection) by F.R.S. Henry Gray (2011) Leather Bound (2010th Edition). Barnes & Noble.

- Moore, K.L., Dalley, A.F., Agur, A.M. (2018). Clinically Oriented Anatomy, 8th Edition, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.