- Anatomical terminology

- Skeletal system

- Joints

- Muscles

- Heart

- Blood vessels

- Lymphatic system

- Nervous system

- Respiratory system

- Digestive system

- Urinary system

- Female reproductive system

- Male reproductive system

- Endocrine glands

- Eye

- Ear

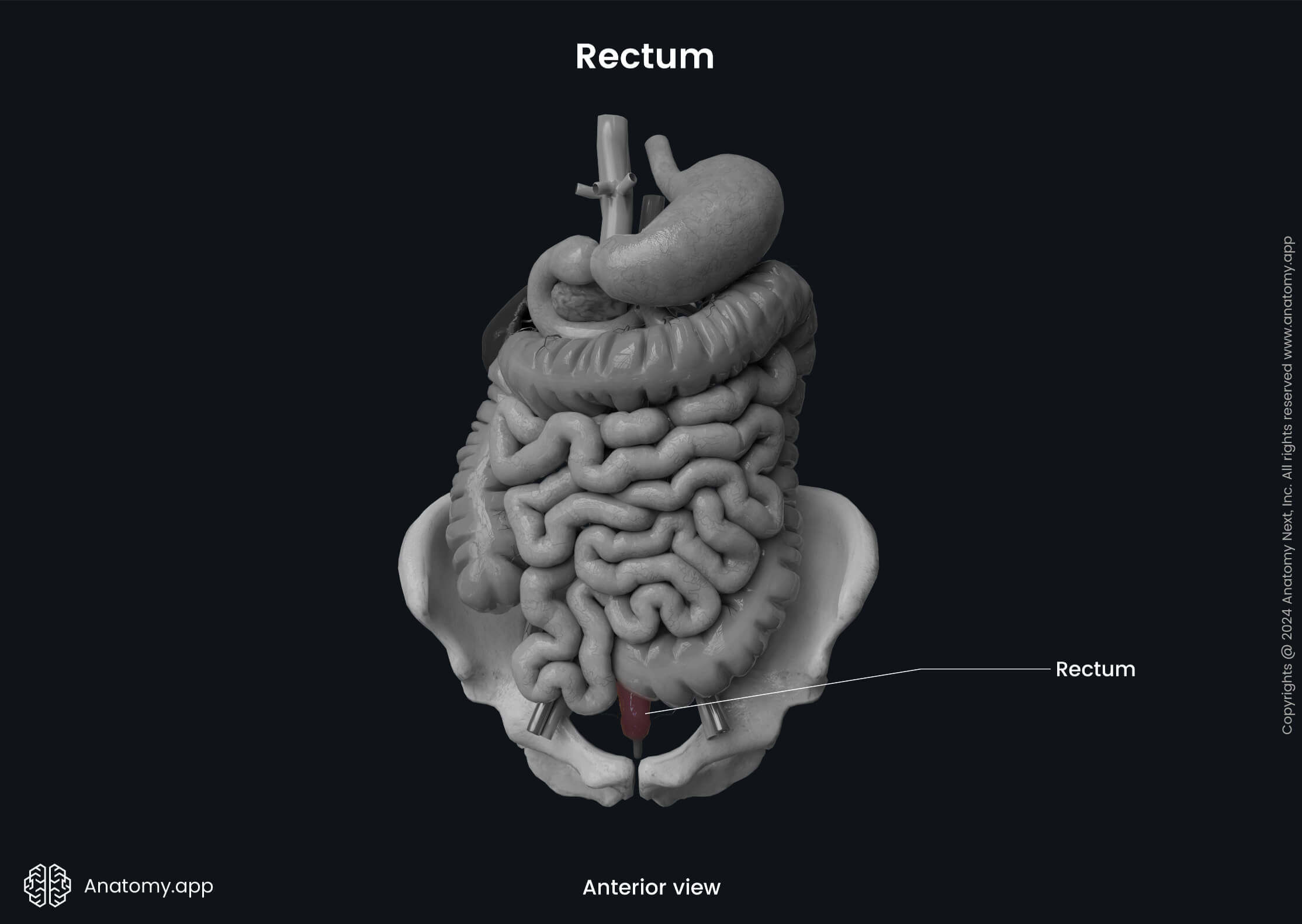

Rectum

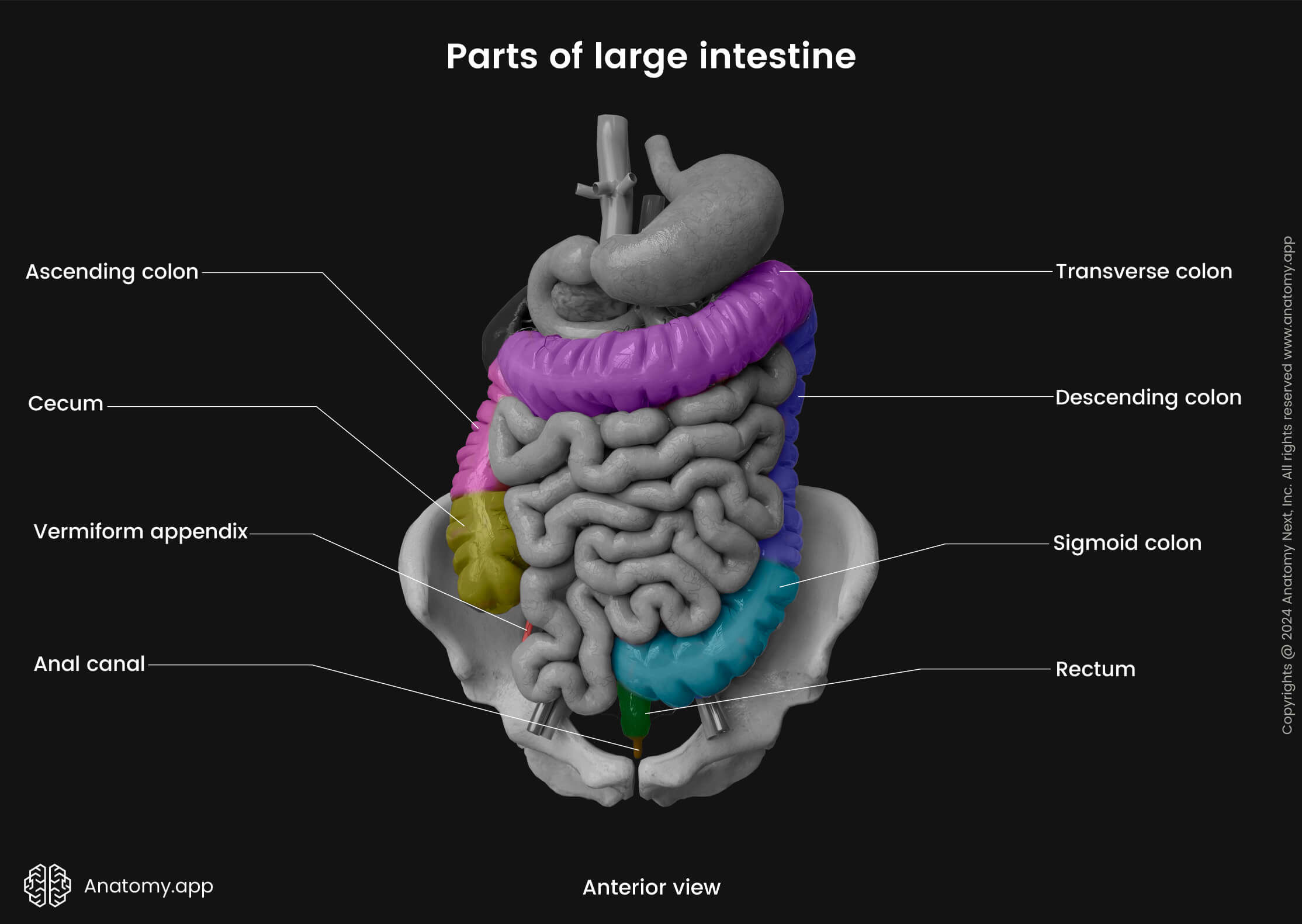

The rectum (Latin: rectum) is the distal part of the large intestine. It is a continuation of the sigmoid colon and is approximately 5 - 6 inches (12 - 15 cm) long. The rectum terminates at the anal canal, which ends with an opening known as the anus. The primary function of the rectum is the temporary storage of feces before their further discharge from the large intestine through the anus during a process known as defecation.

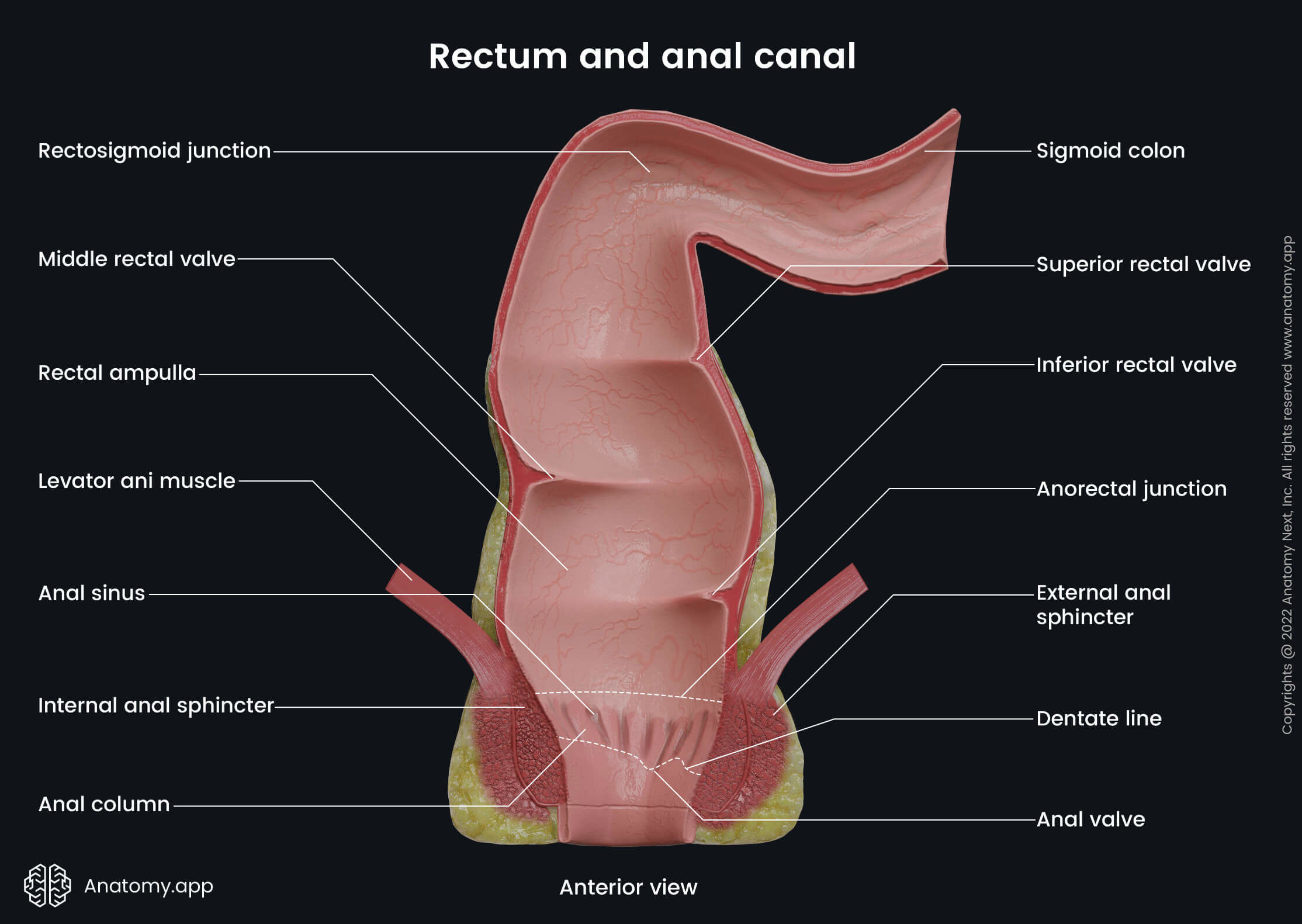

The rectum starts at the rectosigmoid junction, which is its connection site with the sigmoid colon. It projects at the level of the third sacral vertebra (S3). As the rectum passes through the puborectalis of the levator ani muscles (muscles forming the pelvic diaphragm), it continues as the anal canal. The junction between the rectum directed anteriorly and the anal canal directed posteriorly is called the anorectal junction.

Unlike the sigmoid colon, the rectum lacks haustra, taeniae coli, semilunar folds and epiploic appendices. The proximal diameter of the rectum is similar to that of the sigmoid colon, but it enlarges distally and forms a dilation called the rectal ampulla. The rectal ampulla is a terminal part of the rectum that further transitions into the anal canal.

Flexures of rectum

The course of the rectum is marked by two major anteroposterior flexures - sacral and anorectal. The sacral flexure is an anteroposterior curve with anterior concavity because the rectum follows the concavity of the sacrum. The anorectal flexure that corresponds to the anorectal junction is an anteroposterior curve with anterior convexity. It pierces the pelvic diaphragm to become the anal canal. The flexure creates an angle between the rectum and anal canal that projects approximately 1 inch (2.5 cm) below the tip of the coccyx. In males, it also projects at the level of the apex of the prostate, which is located anterior to the rectum.

The rectum has three additional lateral flexures formed by the submucosal transverse folds that protrude into the lumen of the rectum. These submucosal folds are also called the valves of Houston, and they include the following:

- Superior rectal valve - upper convexity on the left side of the rectum;

- Middle rectal valve - intermediate convexity on the right side;

- Inferior rectal valve - lower convexity on the left side of the intestine.

Peritoneal relations and pouches

The rectum can be subdivided into three parts based on its relationship to the peritoneum:

- Upper (proximal) third - located intraperitoneally; the peritoneum covers it anteriorly and laterally;

- Middle third - located behind the peritoneum, meaning it lies retroperitoneally;

- Lower (distal) third - situated below the pelvic diaphragm, and the peritoneum does not cover it; therefore, it has an extraperitoneal position.

The peritoneum not only covers the rectum but also extends to the organs located in front of it, forming several invaginations or so-called pouches. In males, the peritoneum goes from the anterior wall of the rectum to the posterior wall of the urinary bladder, forming the rectovesical pouch. In females, the peritoneum passes from the anterior wall of the rectum to the posterior wall of the uterus, forming the rectouterine pouch (also called the pouch of Douglas).

Related structures

The following structures are located posterior to the rectum: sacrum, coccyx, anococcygeal ligament, presacral fascia, piriformis, levator ani and coccygeus muscles, median sacral, lateral sacral and superior rectal arteries, ganglion impar, lower sacral spinal and coccygeal spinal nerves and the sacral part of the sympathetic trunk.

Laterally lie the lateral rectal ligament, middle rectal artery, pararectal fossa, levator ani and coccygeus muscles, and the inferior hypogastric plexus.

Anterior relations depend on gender. However, anterior to the rectum of both genders are the sigmoid colon and coils of the small intestine (ileum). In men, anterior to it are the base of the urinary bladder, ampulla of the ductus deferens, seminal vesicles, terminal parts of the ureters and prostate, and the rectovesical pouch. In women, anterior to the rectum are the rectouterine pouch, uterus and posterior wall of the vagina.

Rectum histology

The wall of the rectum is composed of similar layers to those of the rest of the large intestine. It consists of the following four layers:

- Mucosa

- Submucosa

- Muscularis externa

- Serosa or adventitia

Mucosa

The mucosa (or mucosal layer) is the inner layer of the rectum that faces its lumen. It is darker, thicker and more vascular in the rectum than in other large intestine portions. Overall, the mucosal layer is composed of three parts - epithelium, lamina propria and muscularis mucosae. The rectum is lined by simple columnar epithelium, except at the anorectal junction, where it flattens and transitions from the simple columnar to the stratified squamous non-keratinized epithelium.

Besides the epithelial cells called enterocytes, the epithelium of the rectal wall also contains numerous goblet cells, enteroendocrine cells and microfold cells (M cells). The primary function of goblet cells is to secrete mucus, while enteroendocrine cells produce hormones. M cells are rare specialized intestinal epithelial cells overlying the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) located below the epithelial layer. They ingest and transport antigen cells.

Overall, the mucosa of the rectum contains numerous intestinal glands (crypts of Lieberkühn) that project deep into the lamina propria. They become shorter and shorter towards the anorectal junction and completely disappear at it.

The lamina propria is a layer of loose connective tissue that provides structural support to the mucosal epithelium. It contains excessive amounts of solitary lymphoid follicles. Besides the follicles, the lamina propria also contains blood and lymph vessels and nerve fibers.

The muscularis mucosae is the muscular layer of the mucosa located at its base. It separates the mucosa from the submucosa. The muscularis mucosae of the large intestine becomes thinner and irregular towards the anorectal junction and disappears at it. Therefore, the lamina propria directly connects with the submucosa at the anorectal junction.

Submucosa

The submucosa or submucosal layer of the rectum is formed by loose connective tissue containing cells such as fibroblasts, macrophages, plasma cells, mast cells and lymphocytes. It is rich with blood vessels, lymphatics, as well as nerve fibers and ganglion cells that form the submucosal nerve plexus called Meissner’s plexus. Also, the rectum contains great amounts of submucosal veins forming the rectal venous plexuses.

Muscularis externa

The muscularis externa (also known as the muscularis propria) lies beneath the submucosa and is composed of two distinct layers containing smooth muscle cells. The outer is the longitudinal layer, while the inner is the circular layer. Between both muscular layers lies the myenteric nerve plexus, known as Auerbach’s plexus.

Serosa/adventitia

The serosa or serous membrane is the outermost layer of the rectal wall covering its upper two-thirds. It is formed by the visceral peritoneum that is lined by a simple squamous epithelium called the mesothelium. The mesothelium is supported by a loose connective tissue layer below it.

The peritoneum does not entirely cover the rectum. The lower third of the rectum and also the dorsal aspects of its middle third are covered by adventitia instead of serosa. The adventitia is the outermost loose connective tissue layer.

Neurovascular supply of rectum

Arterial blood supply

The arterial blood supply of the rectum comes from the superior, middle and inferior rectal arteries. All arteries anastomose with each other and form a strong network. The superior rectal artery is a terminal branch of the inferior mesenteric artery, and it supplies the upper two-thirds of the rectum. The superior rectal artery typically divides into two branches - the right and left.

The middle rectal arteries are usually paired vessels that arise from the internal iliac arteries and supply the lower two-thirds of the rectum. The inferior rectal arteries, on the other hand, are derived from the internal pudendal arteries, and they supply the anorectal junction.

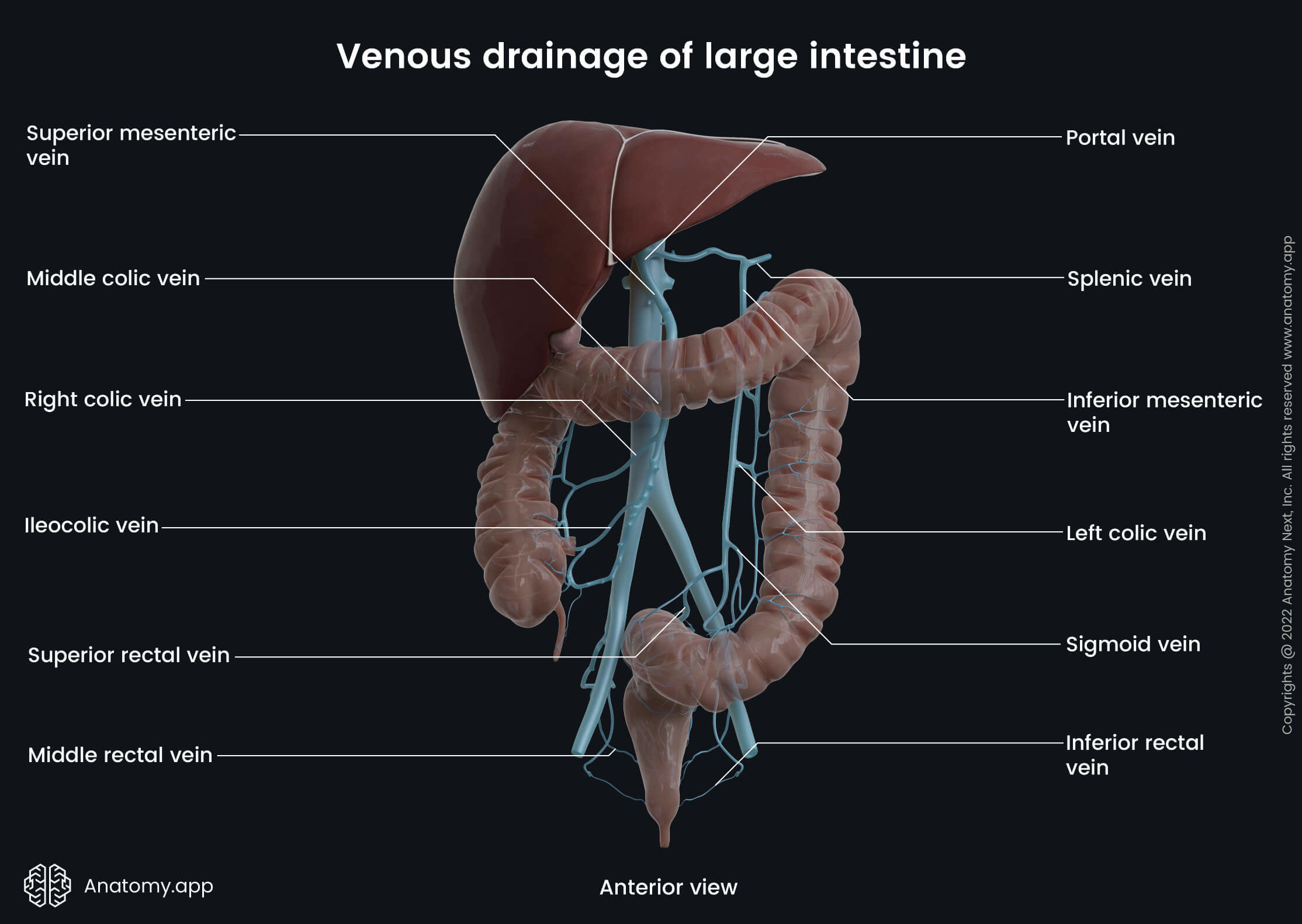

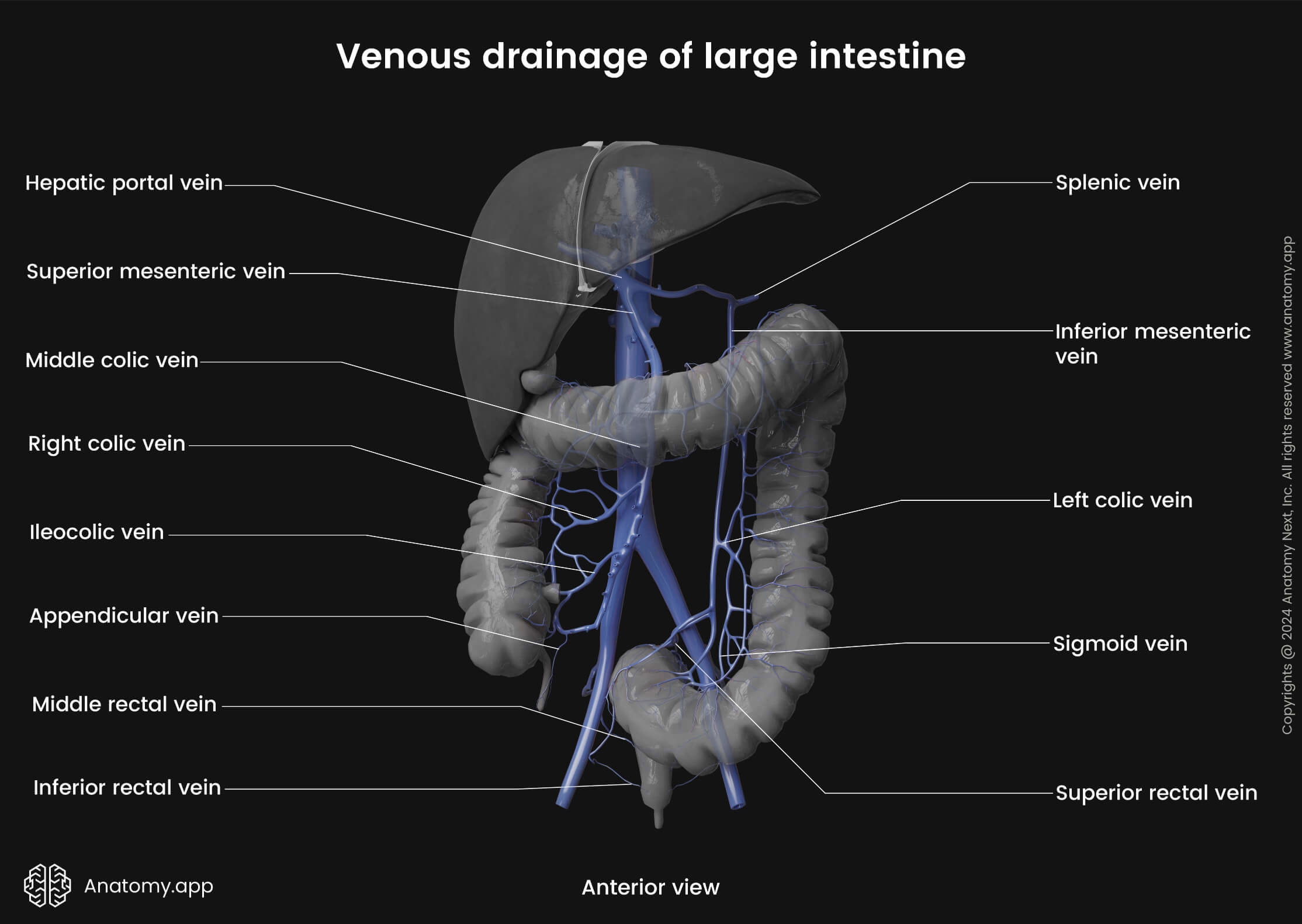

Venous drainage

Similar to the arterial supply, the venous drainage of the rectum is ensured by the same-named veins - superior, middle and inferior rectal veins. The upper two-thirds of the rectum are drained by the superior rectal veins. They are tributaries of the inferior mesenteric vein that usually drains into the splenic vein, which further carries venous blood to the hepatic portal venous system.

The venous drainage of the inferior third of the rectum is provided mainly by the middle rectal veins. However, the inferior rectal veins might also participate in the drainage of the inferior part of the rectum. The middle and inferior rectal veins drain into the internal pudendal and internal iliac veins, which belong to the systemic venous circulation. Both systems (portal and systemic) are connected by numerous clinically important anastomoses.

Lymphatic drainage

The lymphatic drainage of the rectum follows the course of the arteries and veins. The proximal parts of the rectum drain via the inferior mesenteric and pararectal lymph nodes. In contrast, the distal portion of the rectum is drained through the sacral and internal iliac lymph nodes.

Innervation

Similarly to the nerve supply of the rest of the large intestine, the innervation of the rectum is also provided by the intrinsic and extrinsic neurons forming intrinsic and extrinsic nervous systems. The intrinsic nervous system is located within the rectal wall, and it is referred to as the enteric nervous system consisting of two nerve plexuses (Meissner’s and Auerbach’s plexuses) that provide local, autonomous functions. However, the intrinsic nervous system also receives input from the extrinsic nervous system.

On the other hand, the extrinsic nervous system includes efferent and afferent nerves that primarily come from external sources. They originate from either the brain or spinal cord of the central nervous system. The extrinsic nervous system includes sympathetic and parasympathetic nerve fibers of the autonomic nervous system and sensory nerve fibers provided by the somatic nervous system.

Enteric nervous system

The enteric nervous system includes two nerve plexuses, and they are as follows:

- Submucosal plexus (also called the Meissner’s plexus) - located in the submucosa; innervates the muscularis mucosae layer and crypts of Lieberkühn; therefore, it ensures the secretion of the intestinal glands;

- Myenteric plexus (also known as Auerbach’s plexus) - situated in the muscularis externa between its circular and longitudinal layers; innervates both layers and provides their movements; therefore, it is indirectly involved in the propulsion of feces.

Autonomic nervous system

The autonomic nervous system ensures sympathetic and parasympathetic nerve supply to the rectum. The sympathetic innervation comes from the lumbar splanchnic nerves originating at the first two lumbar segments of the spinal cord (L1 - L2). The lumbar splanchnic nerves synapse with the neurons in the aortic and inferior mesenteric plexuses.

The parasympathetic supply of the rectum is ensured by fibers of the vagus nerve (CN X). They are provided via the pelvic splanchnic nerves (arising from the S2 - S4 spinal cord segments) that enter the inferior hypogastric plexuses.

Rectum functions

The main function of the rectum is to temporarily store and eliminate feces in a process known as defecation. Defecation involves a coordinated action of the colon, rectum, pelvic diaphragm and anal sphincters.

The rectum temporarily stores feces, and it is also possible to relax its wall to stop the fecal matter and flatus (gasses) from moving further if the urge to defecate or let off the gas happens to be not at the right timing and can be considered as inappropriate. When a conscious decision to defecate is made, a combination of colonic and rectal contractions, raised intra-abdominal pressure from straining, and relaxation of the anal sphincters and puboanalis muscle ensures the evacuation of feces from the human body out into the environment.

References:

- Drake, R., Vogl, W., & Mitchell, A. (2019). Gray’s Anatomy for Students: With Student Consult Online Access (4th ed.). Elsevier.

- Gray, H., & Carter, H. (2021). Gray’s Anatomy (Leatherbound Classics) (Leatherbound Classic Collection) by F.R.S. Henry Gray (2011) Leather Bound (2010th Edition). Barnes & Noble.

- Feather, A., Randall, D., & Waterhouse, M. (2022). Kumar and Clark’s Clinical Medicine. Elsevier (INR) - D.

- Moore, K.L., Dalley, A.F., Agur, A.M. (2018). Clinically Oriented Anatomy, 8th Edition, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Qayed, E., & Shahnavaz, N. (2021). Sleisenger and Fordtran’s Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease Review and Assessment (11th ed.). Elsevier.

- Townsend, C. M., Jr. (2021). Sabiston Textbook of Surgery. Elsevier Gezondheidszorg.