- Anatomical terminology

- Skeletal system

- Skeleton of trunk

- Skull

- Skeleton of upper limb

- Skeleton of lower limb

- Joints

- Muscles

- Heart

- Blood vessels

- Lymphatic system

- Nervous system

- Respiratory system

- Digestive system

- Urinary system

- Female reproductive system

- Male reproductive system

- Endocrine glands

- Eye

- Ear

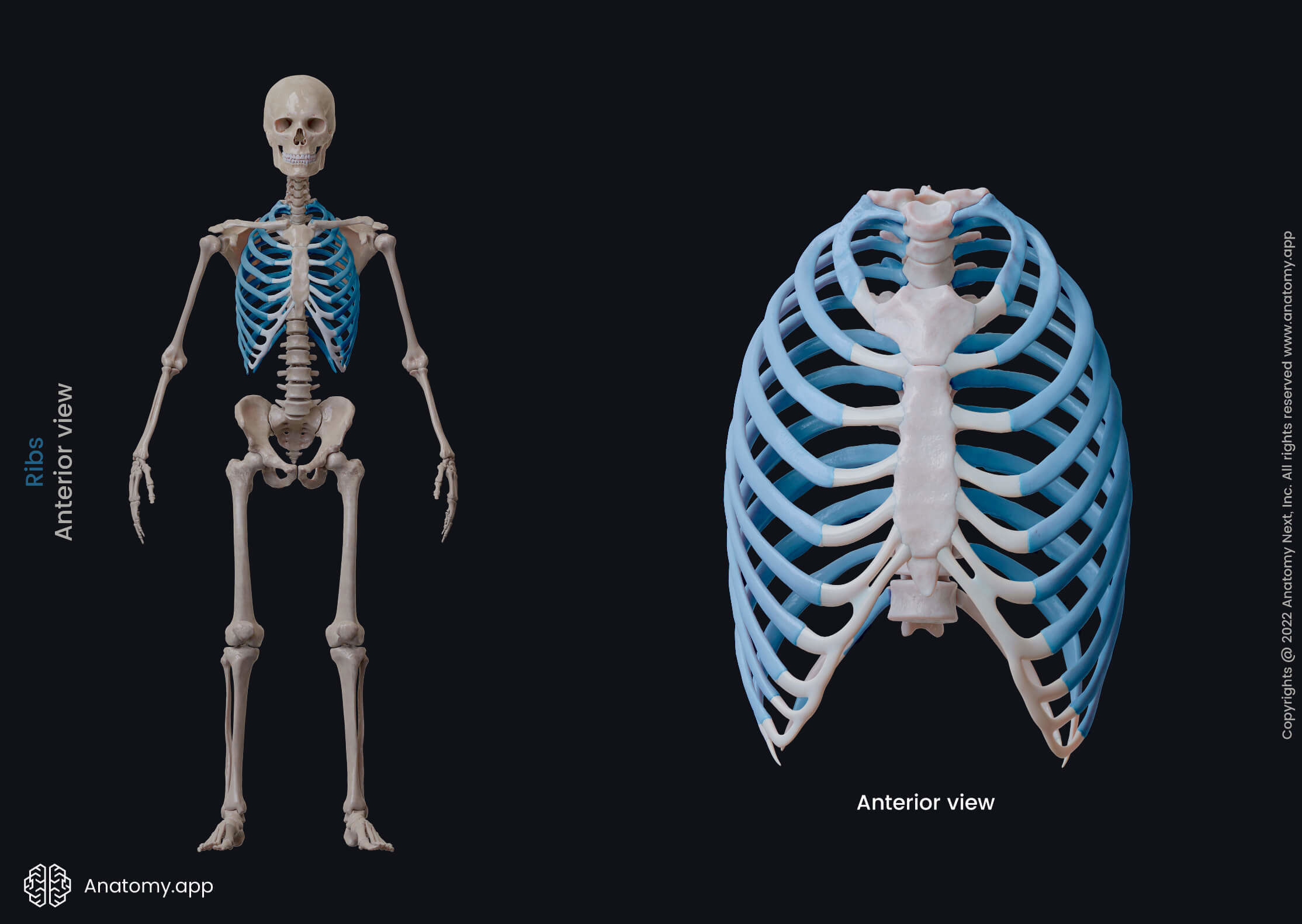

Ribs

The ribs (Latin: costae) are long, flat and curved bones. They articulate with vertebrae of the thoracic spine forming the majority of the rib cage. The rib cage provides support and protection for such vital internal organs as the heart, lungs, spleen, and liver, as well as major blood vessels. Ribs also provide attachment sites for thoracic muscles.

Rib anatomy

There are 12 pairs of ribs, although in rare cases, some ribs can be absent. Ribs have a bony part posteriorly and a cartilaginous part in the front. Between two adjacent ribs is the intercostal space. Each rib articulates with a vertebral body in two following joints:

- Costovertebral joint - between the head of the rib and facets of two neighboring vertebral bodies;

- Costotransverse joint - between the costal tubercle and the transverse process of the vertebrae.

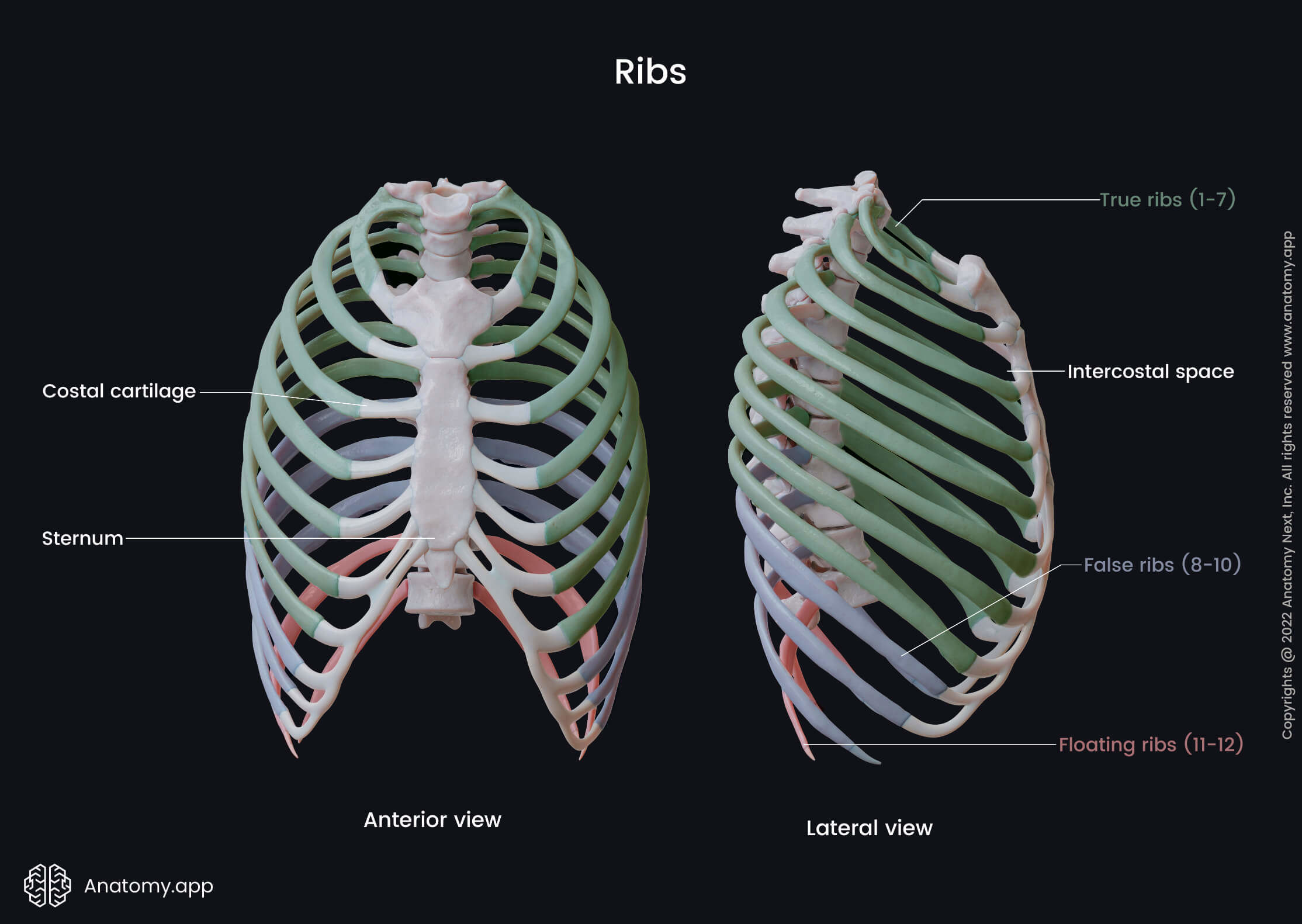

Based on the articulations, ribs can be classified into three major groups:

- The first seven pairs of ribs (1 - 7) are directly connected with the sternum at the sternocostal joints. They are called the true ribs.

- Ribs 8 through 10 join the costal cartilages of upper ribs and attach indirectly by interchondral joints; thus, they are termed as false ribs.

- Ribs 11 and 12 are not connected to the sternum or other ribs at all (floating or free ribs). Their cartilages tend to end within the abdominal musculature.

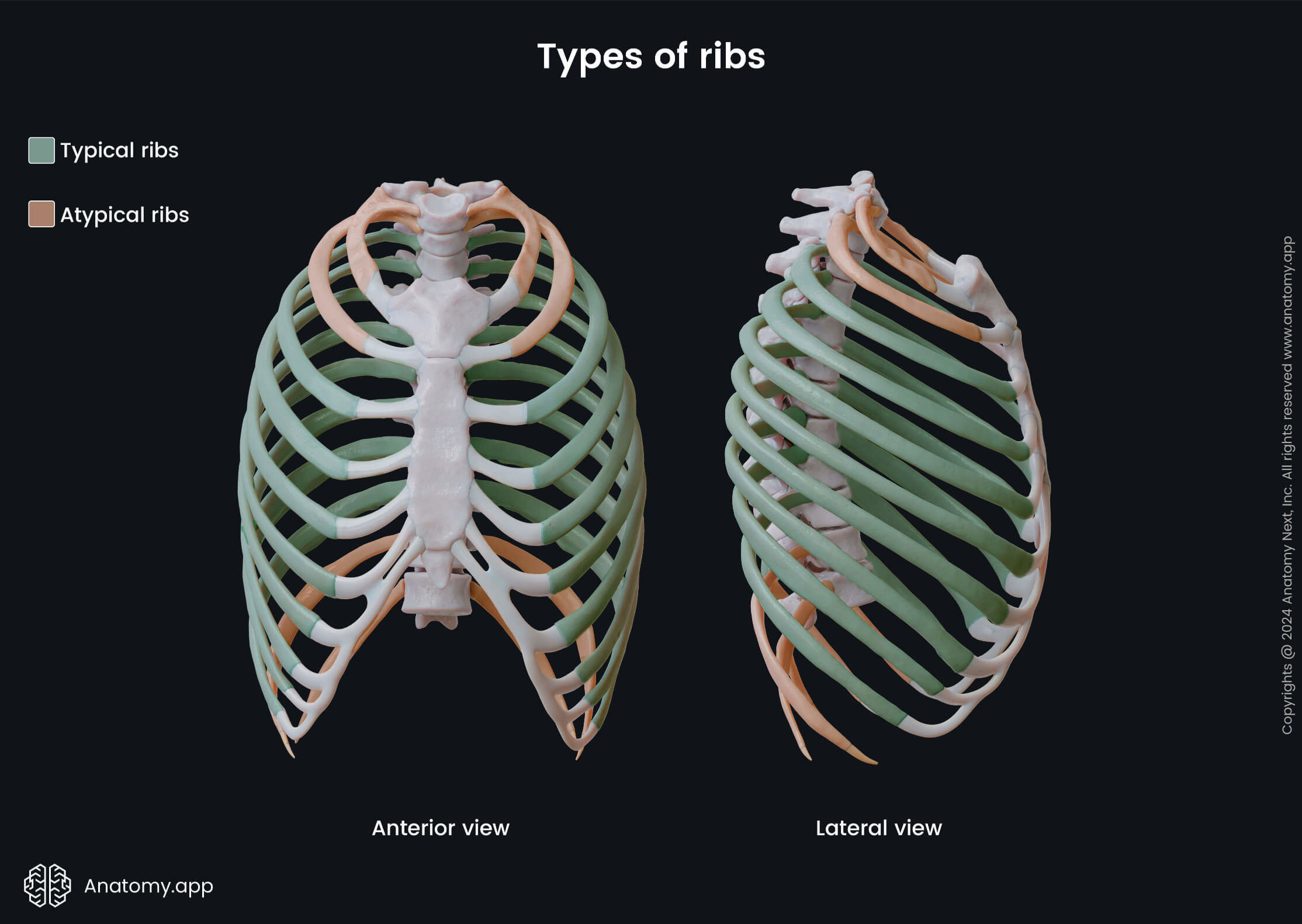

Based on their structural characteristics, ribs can also be classified as either typical or atypical. The typical ribs have a generalized structure making these ribs similar The atypical ribs have variations of this structure. The first two and the last three ribs have distinctly unique features. The rest of the ribs are considered to be typical.

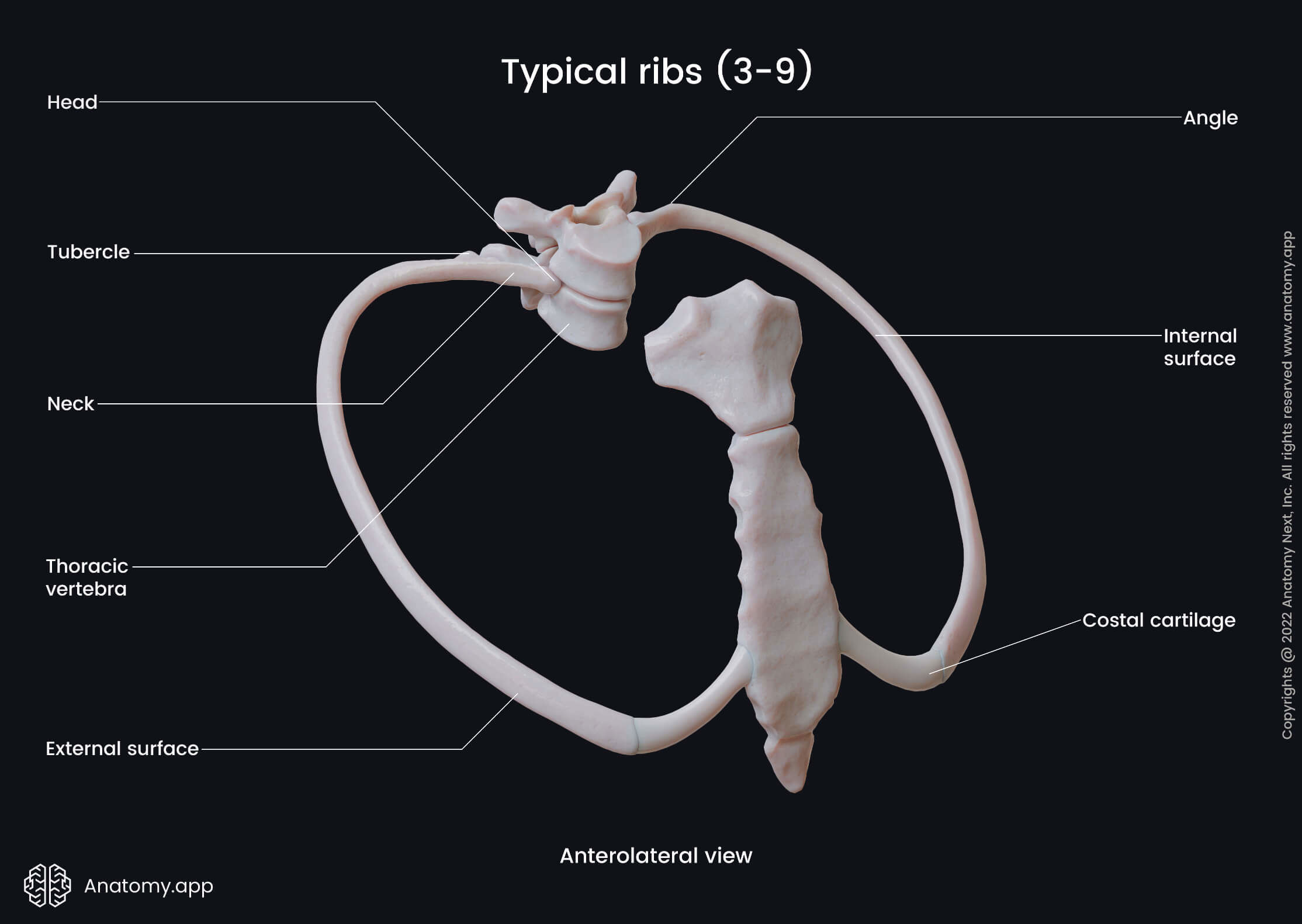

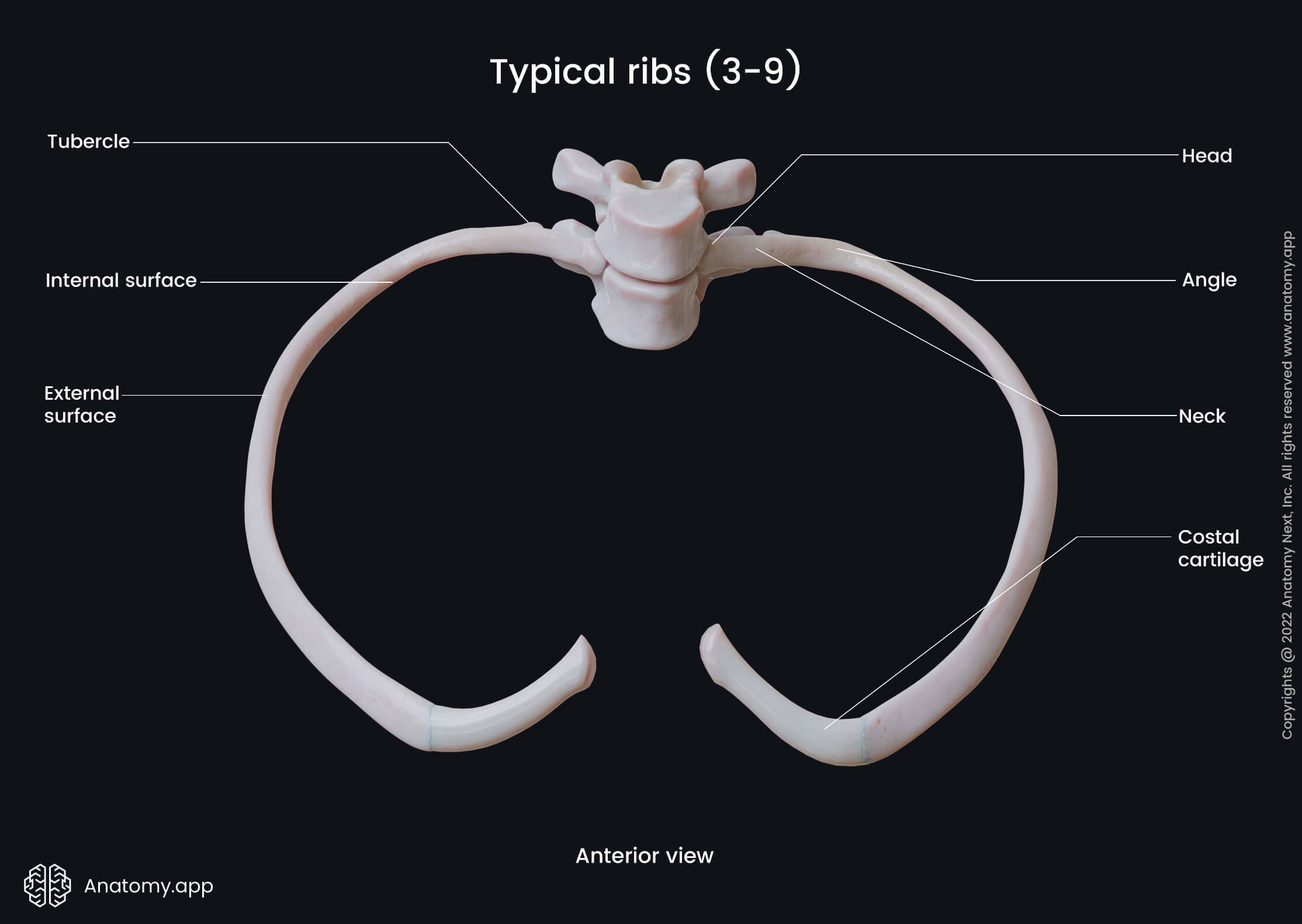

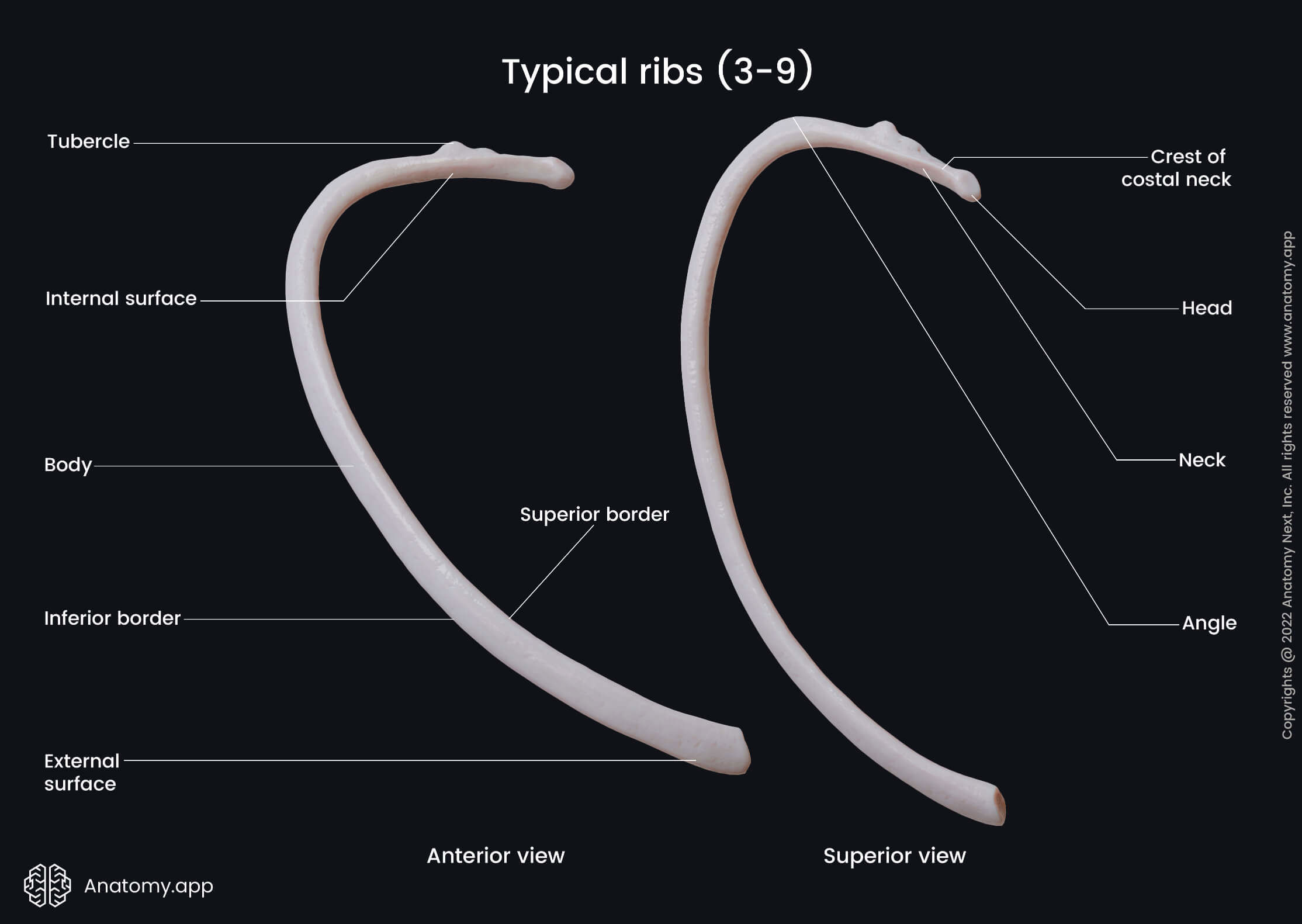

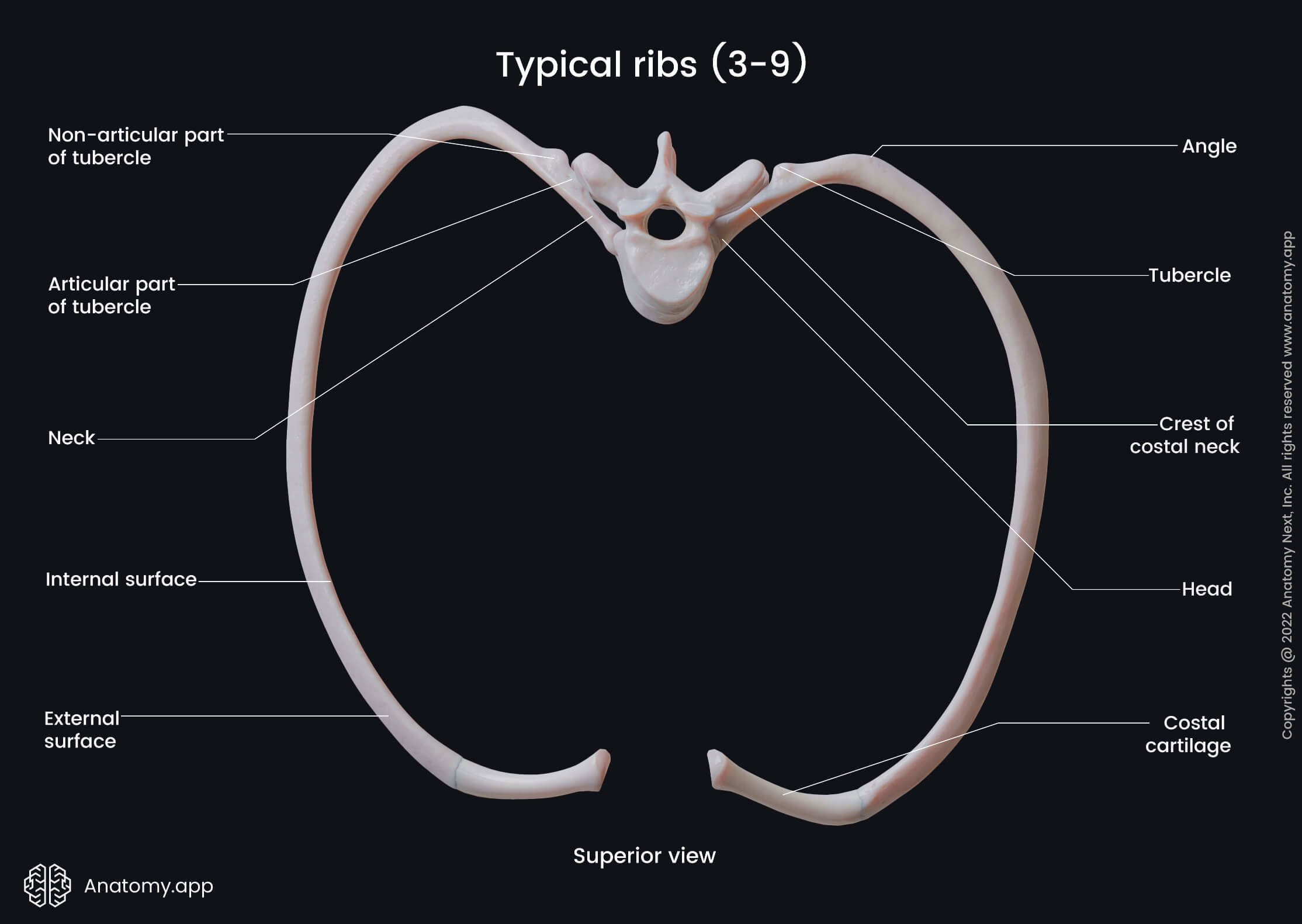

Typical ribs

Ribs 3 to 9 are typical. They have the following similar characteristics: a head, neck, tubercle and body. The head articulates with the body of the thoracic vertebrae by two articular facets. The upper, more prominent facet connects to the corresponding vertebra. The lower, smaller facet articulates with the body of the vertebra above.

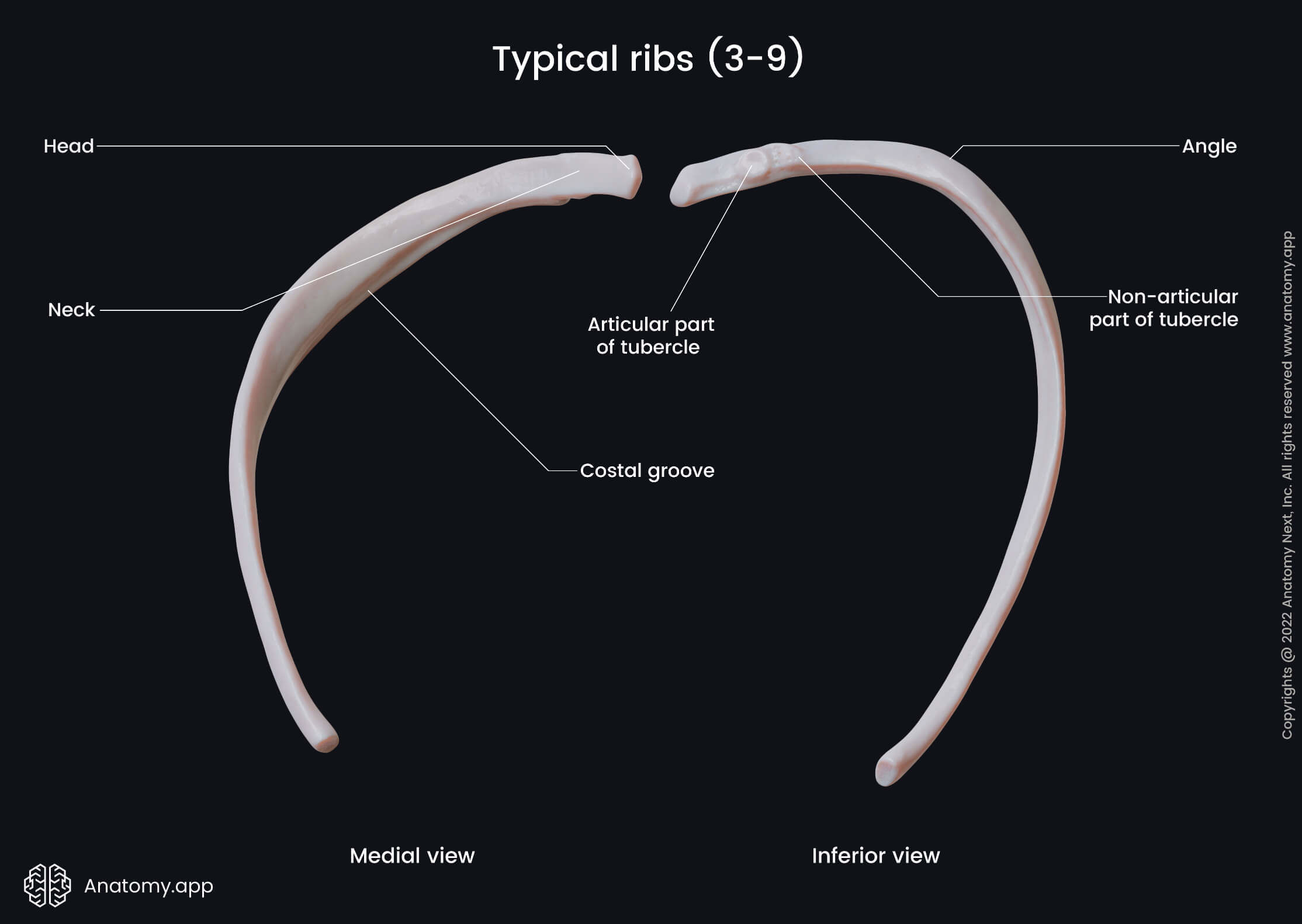

The neck is a flat part distal from the head, connecting it to the body of the rib. The tubercle marks the junction between the neck and the body. It is located posteriorly and articulates with the transverse process of the corresponding vertebra forming the costotransverse joint. A costotransverse ligament also attaches to the tubercle laterally to this joint.

The body is thin and flat, with external and internal surfaces and superior and inferior borders. As the body curves anteriorly, it forms the angle of the rib (costal angle). The costal angle provides attachment sites for deep back muscles. The anterior aspects of ribs continue as the costal cartilages, most of which are attached to the parts of the sternum.

On the inner surface of the body at the inferior margin lies the costal groove. It contains the intercostal nerves and blood vessels (arteries and veins). These structures are organized in the following order: the highest is the intercostal vein, the intercostal artery lies in the middle, and the nerve is located inferiorly. The intercostal nerve is usually not protected by the costal groove. A simple acronym to remember the order of structures in the costal groove is VAN (Vein, Artery, Nerve).

Vascular supply and innervation

Anteriorly, the typical ribs are supplied by branches of the internal thoracic artery in the upper six intercostal spaces or musculophrenic artery in the intercostal spaces below. The posterior aspects of the ribs receive supply from the posterior intercostal arteries branching off the descending aorta. Venous drainage is provided by intercostal veins that flow into the azygos or brachiocephalic veins. Innervation comes directly from the intercostal nerves located in the costal grooves.

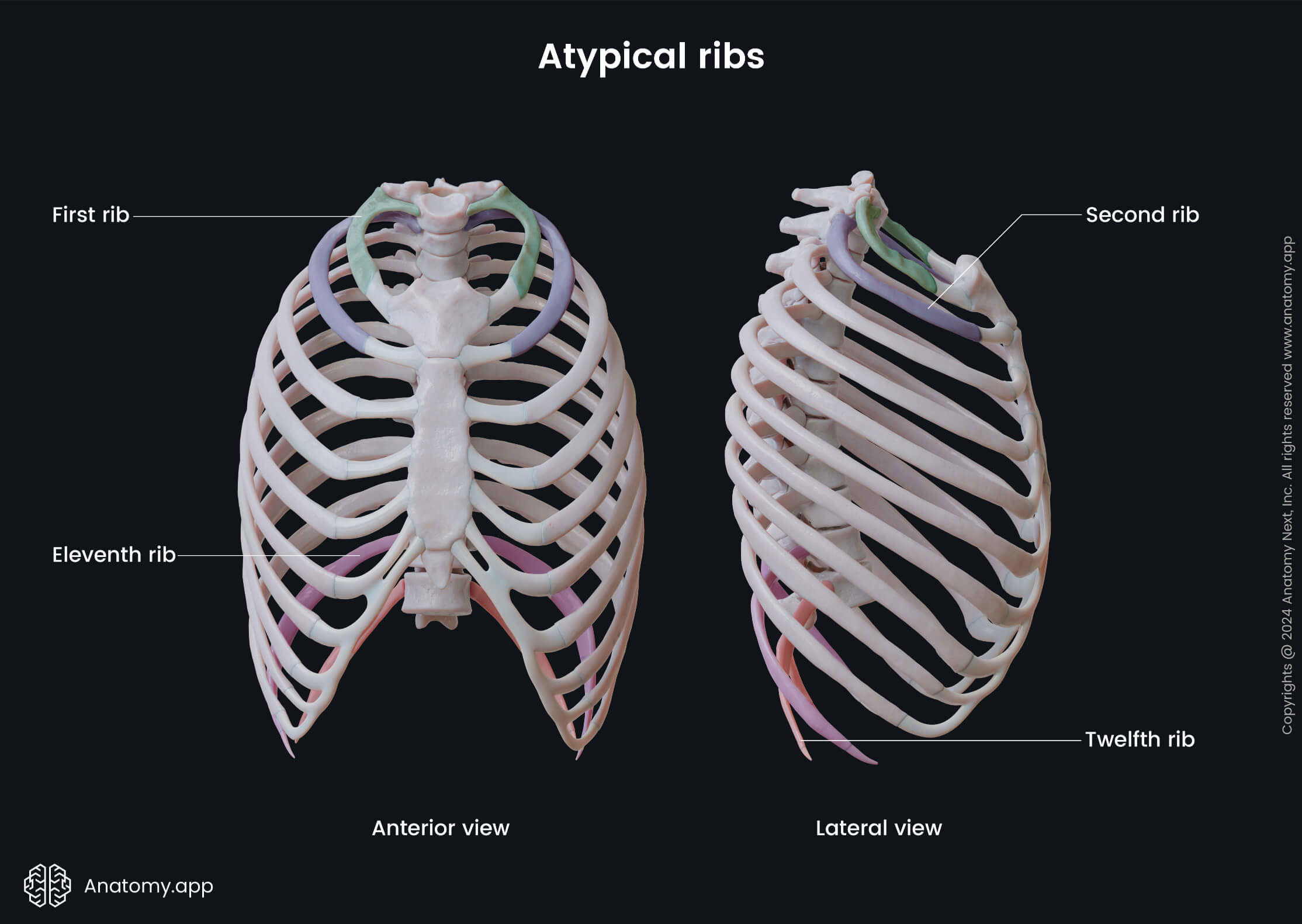

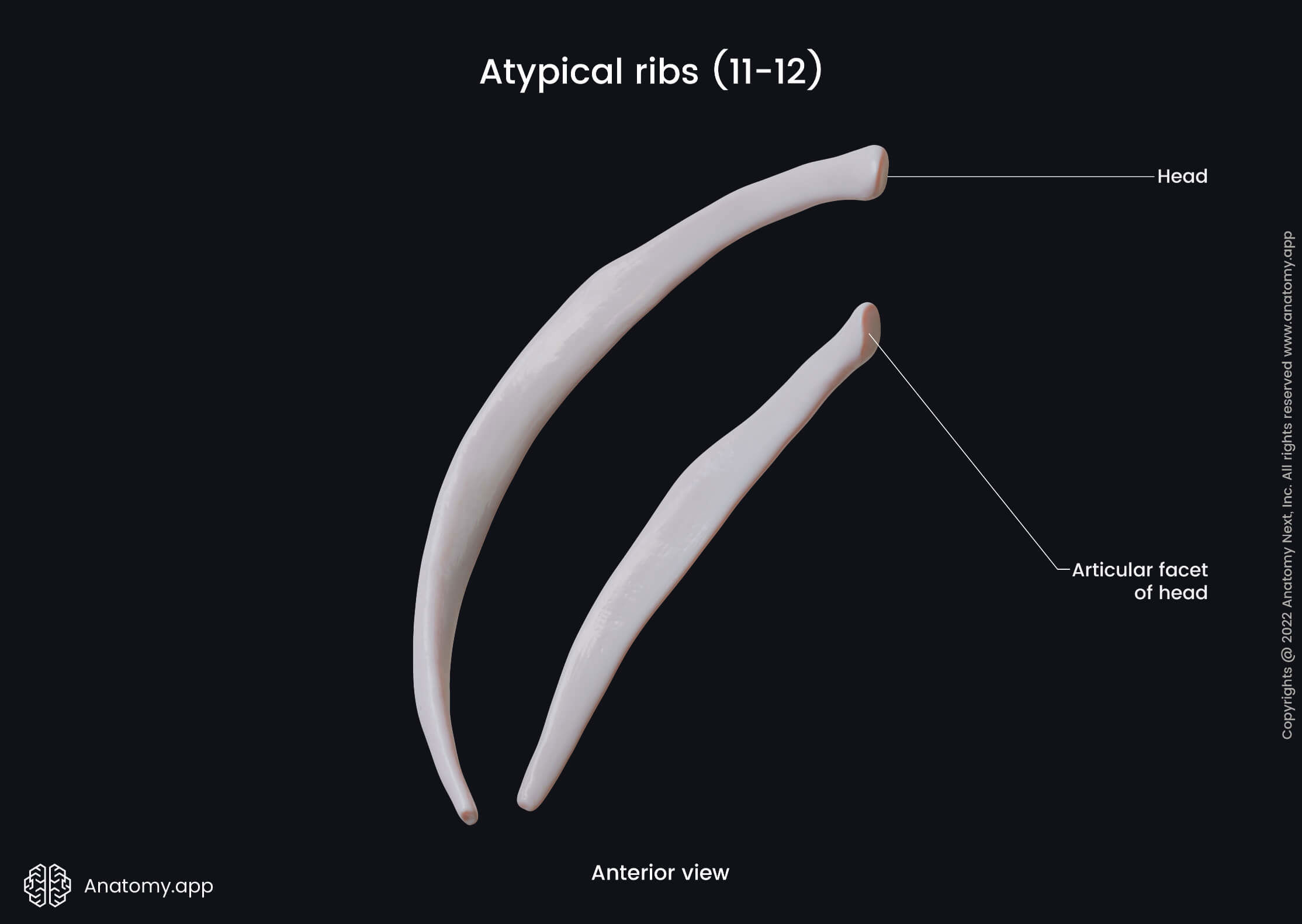

Atypical ribs

Ribs 1, 2, 11 and 12 are atypical ribs because they do not share the same features as typical ribs. Generally, the first and the last two or three ribs have a single articular facet. There is no intraarticular ligament and, therefore, only one synovial cavity. Typical ribs, in contrast, have two synovial cavities. The last three ribs lack synovial joints between the tubercle and the respective vertebral transverse process.

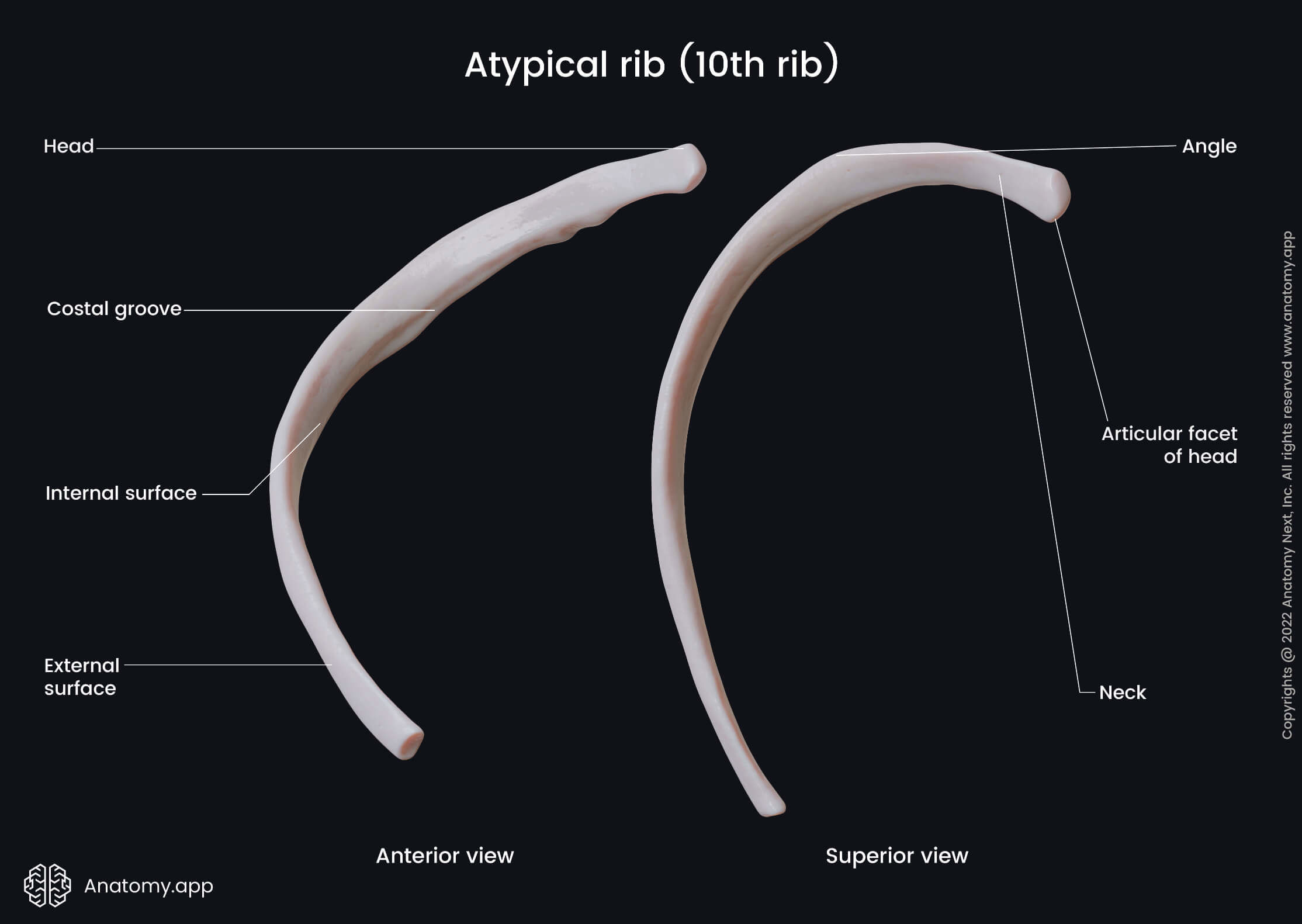

Note: The tenth ribs can be either typical or atypical, depending on their articulations with the bodies of the ninth and tenth thoracic vertebrae. If the tenth rib articulates with both bodies of the mentioned vertebrae, it is classified as a typical rib - its head will have two articular demi-facets. If the tenth rib articulates with only the body of the tenth thoracic vertebra (T10), it will be classified as an atypical rib. Moreover, there will be only one facet on its head.

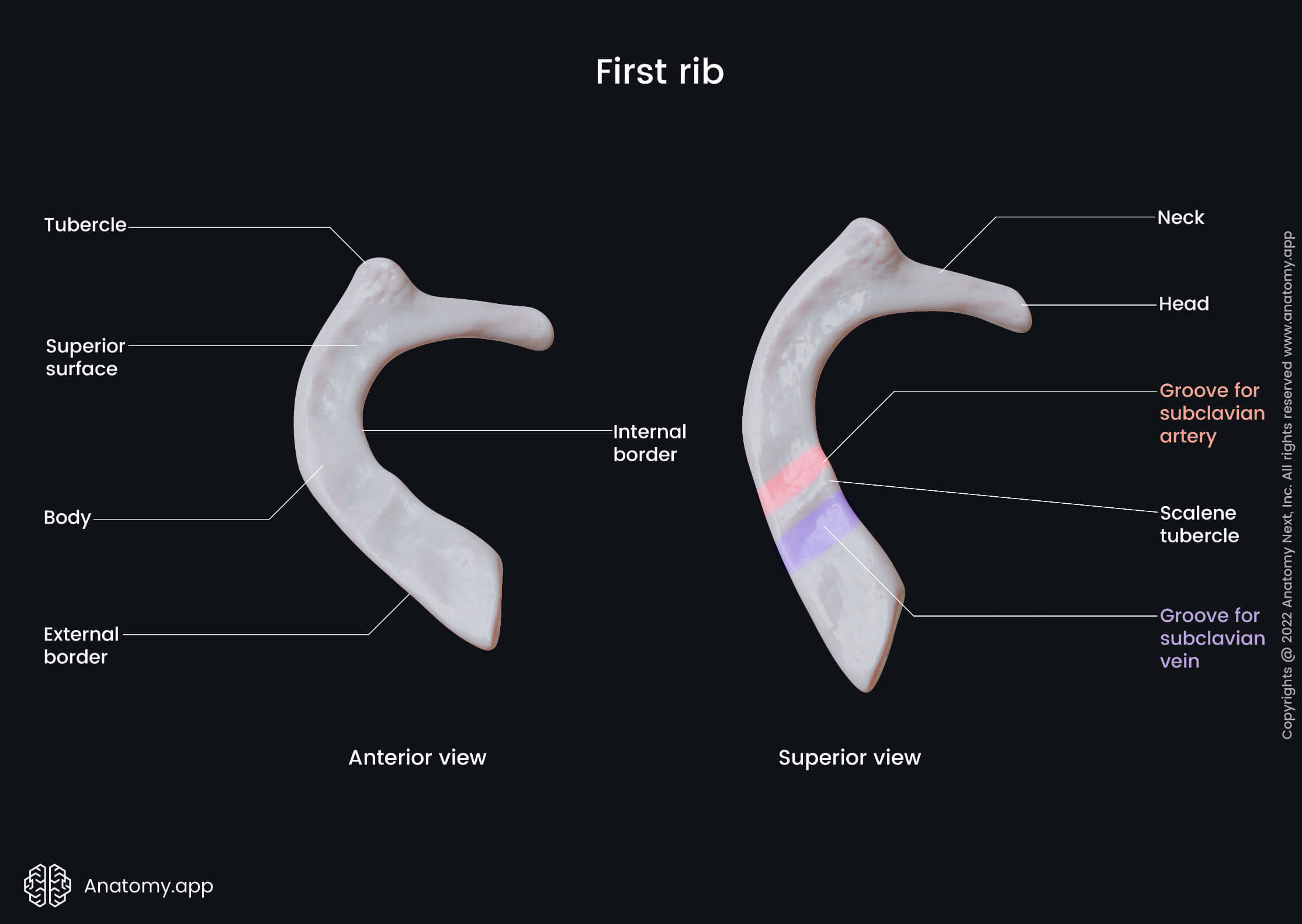

First rib

The first rib is the shortest and widest of all, and it is positioned obliquely, unlike other ribs. The 1st rib allows the lung apex to expand beyond the superior thoracic opening into the lower neck. Due to a different plane, the first rib has superior and inferior surfaces, internal and external borders. The head has only one articular facet. The tubercle corresponds to the costal angle and has a facet to articulate with the first thoracic vertebra.

The distinguishing features of the first rib are found on its superior surface and are the following:

- Scalene tubercle - serves as an attachment site for the anterior scalene muscles;

- Groove anterior to the scalene tubercle where the subclavian vein passes;

- Groove posterior to the tubercle that holds the subclavian artery and the lower trunk of the brachial plexus.

The blood supply of the first rib is ensured by the supreme intercostal and internal thoracic arteries. Venous drainage occurs through the supreme intercostal veins. And innervation is provided by the first intercostal nerve.

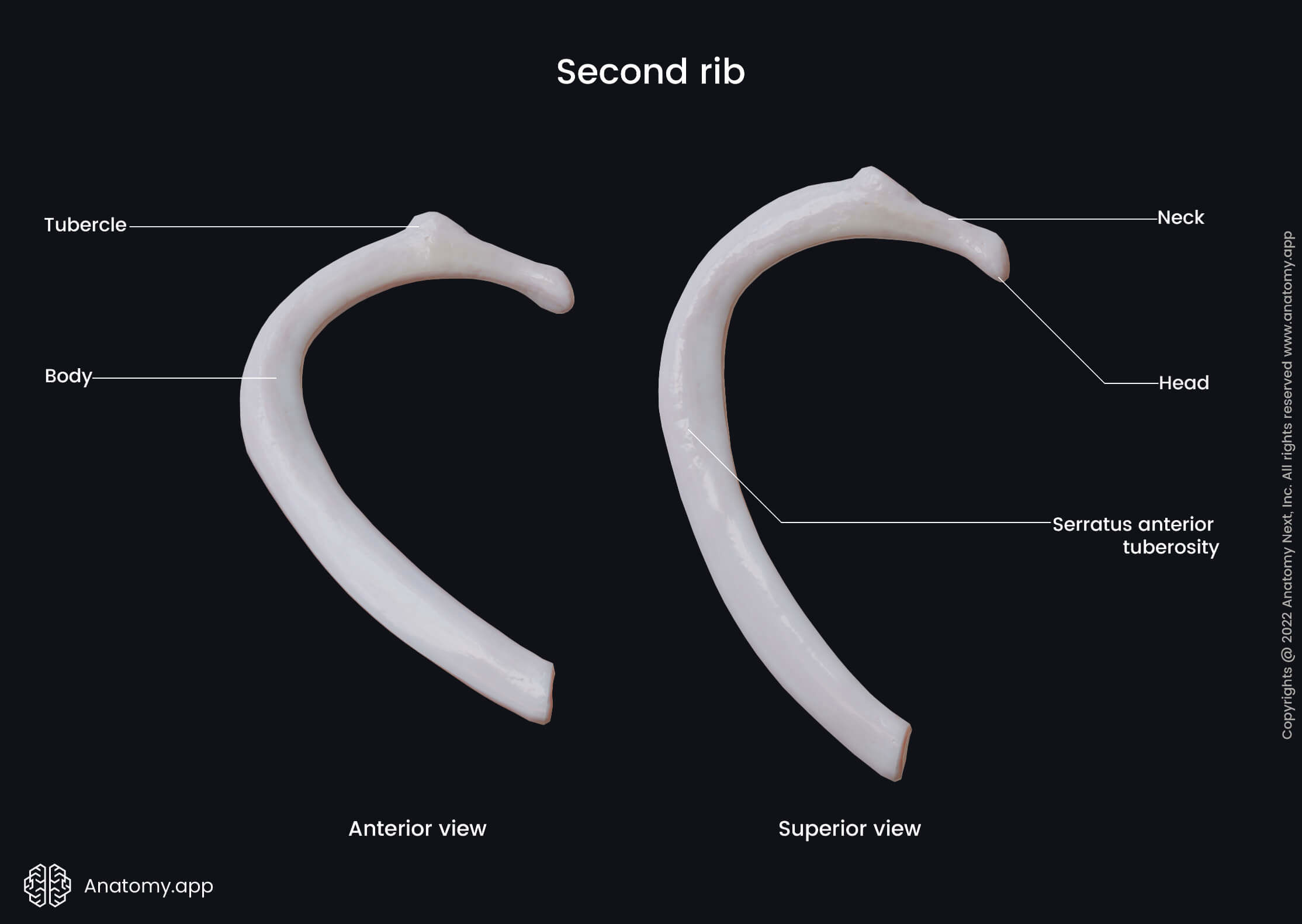

Second rib

The second rib is twice as longer and thinner than the first rib, and its head has two articular facets. The main unique features of this rib are on the external (superior) surface. Around the midpoint, the superior surface has a prominence (serratus anterior tuberosity) where a part of the serratus anterior muscle attaches. Additionally, anteriorly to the costal angle is a ridge that serves as an attachment site for the posterior scalene and serratus posterior superior.

The main vessels providing arterial blood supply to the second rib are also the supreme intercostal and internal thoracic arteries. Drainage occurs through the superior intercostal vein that flows into the brachiocephalic vein. The 2nd rib is innervated by the second intercostal nerve.

Tenth, eleventh, twelfth ribs

In up to 70% of cases, the tenth rib can be free or floating. In the remaining cases, it attaches to the ninth rib by a fibrous joint. The head of the tenth rib has only one facet to articulate with the body of the tenth thoracic vertebra.

The eleventh and twelfth ribs also have a single large articular facet on their heads. They have no necks or tubercles, and their ends are covered by hyaline cartilage. Various muscles and ligaments attach to the twelfth rib, for example, quadratus lumborum, diaphragm and internal intercostal muscles.

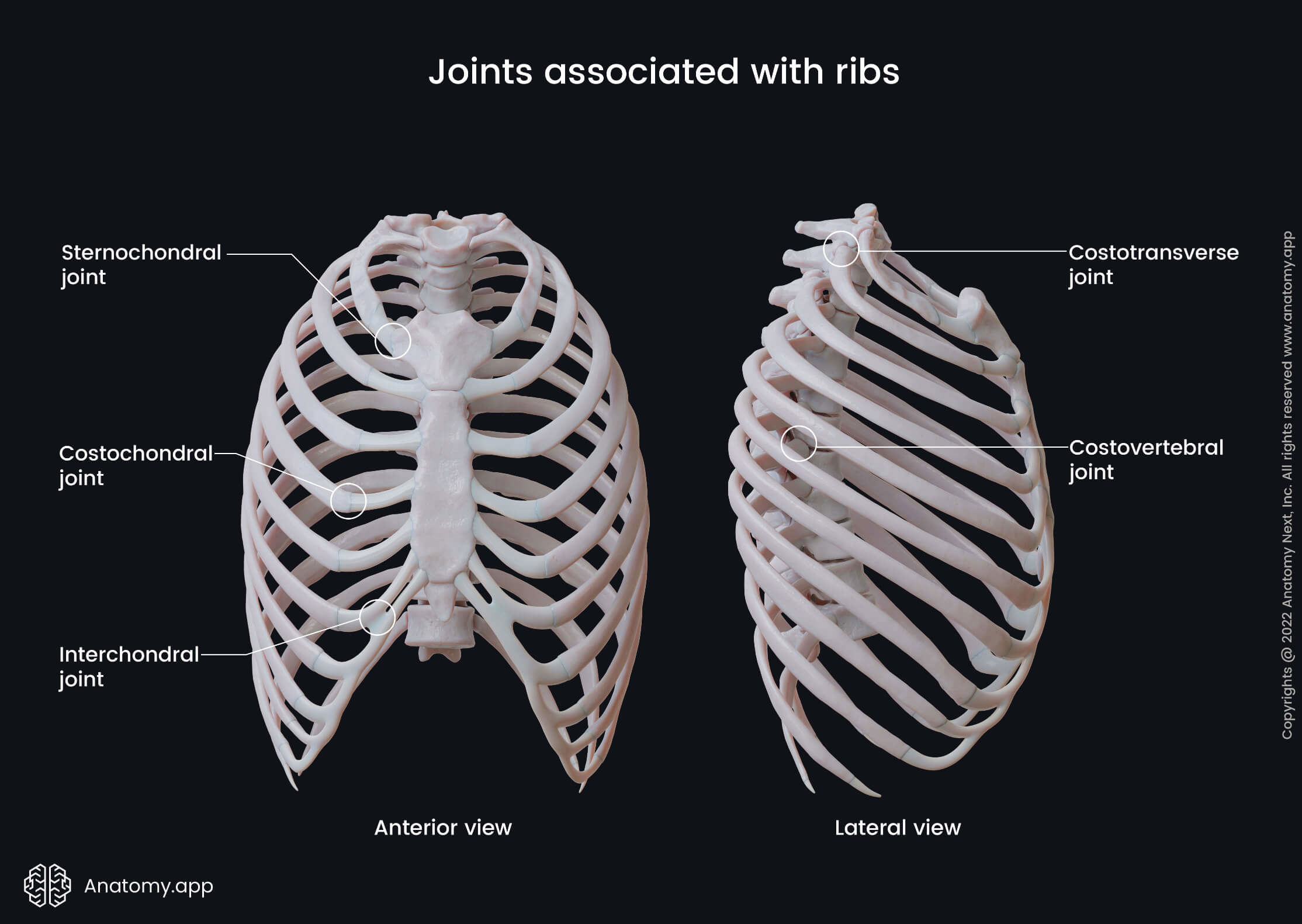

Joints associated with ribs

There are various types of joints associated with ribs, and they are mainly cartilaginous or synovial. A cartilaginous joint means that the connected bones are lined by hyaline or fibrous cartilage. These types of joints usually are fixed (termed synarthroses) or with slight mobility (called amphiarthroses).

Cartilaginous joints can be divided into primary and secondary, depending on the type of hyaline involved. Primary cartilaginous joints (synchondroses) are between the bones and the hyaline cartilage. Secondary cartilaginous joints (symphyses) are made up either of hyaline cartilage or fibrocartilage.

Synovial joints are diarthroses - they can move in various planes but are restricted in motion to the surrounding muscles and ligaments. The main characteristic of these joints is the synovial cavity, synovial capsule and synovial membrane. The bones of the synovial joints are lined by hyaline cartilage.

Note: to read more in detail about the types of joints and their function, please see our article on the classification of joints.

The joints associated with ribs are the following:

- Sternochondral synchodrosis of first rib - between the sternum and costal cartilage of rib 1; it is considered to be primary cartilaginous joint;

- Sternochondral joints - between the sternum and costal cartilages of ribs 2 to 7; they are synovial plane-type joints;

- Costochondral joints - between costal cartilages and ribs; these are primary cartilaginous joints, called synchondroses;

- Costovertebral joints - between the vertebrae and ribs;

- Joint of head of rib - between the head of the rib and the body of the corresponding vertebra; it is a synovial plane-type of joint;

- Costotransverse joints - between the costal tubercle and the transverse process of the vertebrae; also a synovial plane type joint;

- Interchondral joints – between two or more costal cartilages. The cartilages are connected by the synovial plane joints and stabilized by attaching interchondral ligaments. An exception is the tenth rib that attaches to the ninth rib by a fibrous type of joint.

Clinical considerations

Some areas of clinical interest related to ribs may include rib fractures and pleural drainage. Most rib fractures occur due to blunt trauma. They are also common in the elderly population because of falls. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation frequently results in anterior rib fractures.

Pleural drainage is a very common procedure, especially in the emergency department. During the procedure, a tube is inserted into an intercostal space (space between ribs) to reach the pleural cavity. It is done to remove excess fluid or accumulated air from the pleural cavity.

Rib fractures

Rib fractures are the most common form of rib injury due to thoracic trauma. The main problem usually is not the fracture itself but the possible damage of underlying vital organs. In general, isolated rib fractures can heal in several weeks and require only conservative treatment (i.e., rest and pain medication).

The most commonly fractured ribs are the 5th through 9th ribs. It is important because these particular ribs are the most involved in the respiration process. The weakest structural point to fracture is next to the costal angle. Rib fractures usually manifest as limited inspiration due to sharp pain.

Multiple fractures may result in a dangerous condition called the flail chest. It is when the chest wall moves paradoxically (inwards) to inspiration. These patients should be closely observed as they may require mechanical ventilation.

Pleural drainage

Pleural drainage (also named thoracentesis) is an insertion of a so-called chest tube in the pleural space. It is done in order to diagnose or treat excessive fluid or air. The procedure can alleviate breathing difficulties when there is too much pleural effusion, for example. It can also help to understand and specify the disease by examining the fluid sample.

The typical chest tube insertion sites are usually 7th to 9th intercostal spaces between middle axillary and posterior axillary lines. Ultrasonography can confirm the best puncture site. It is extremely important to avoid the neurovascular bundle (intercostal artery, vein and nerve) at the inferior margin of the rib. Therefore the chest tube is inserted near the superior margin only.

References:

- Brauner, M., Monsenifar, Z. (2020) Thoracentesis technique. Emedicine.Medscape.Com https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/80640-technique#c2

- Cameron, A. (2019). Current Surgical Therapy (13th ed.). Elsevier.

- Gray, H., & Carter, H., V. (2021). Gray’s Anatomy (Leatherbound Classics) (Leatherbound Classic Collection) by F.R.S. Henry Gray (2011) Leather Bound (2010th Edition). Barnes & Noble.

- Henry, T. S., Donnelly, E. F., Boiselle, P. M., Crabtree, T. D., Iannettoni, M. D., Johnson, G. B., Kazerooni, E. A., Laroia, A. T., Maldonado, F., Olsen, K. M., Restrepo, C. S., Shim, K., Sirajuddin, A., Wu, C. C., & Kanne, J. P. (2019). ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Rib Fractures. Journal of the American College of Radiology, 16(5), S227–S234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2019.02.019

- Iannotti, J. P., & Parker, R. (2013). The Netter Collection of Medical Illustrations: Musculoskeletal System, Volume 6, Part III - Musculoskeletal Biology and Systematic Musculoskeletal Disease (Netter Green Book Collection) (2nd ed.). Saunders.

- Kuo, K., & Kim, A. (2021, January). Rib fracture. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/ NBK541020/

- Sellke, F., del Nido, P., & Swanson, S. (2015). Sabiston and Spencer Surgery of the Chest: 2-Volume Set (9th ed.). Elsevier.