- Anatomical terminology

- Skeletal system

- Joints

- Muscles

- Heart

- Blood vessels

- Lymphatic system

- Nervous system

- Respiratory system

- Digestive system

- Urinary system

- Female reproductive system

- Male reproductive system

- Endocrine glands

- Eye

- Ear

Jejunum and ileum

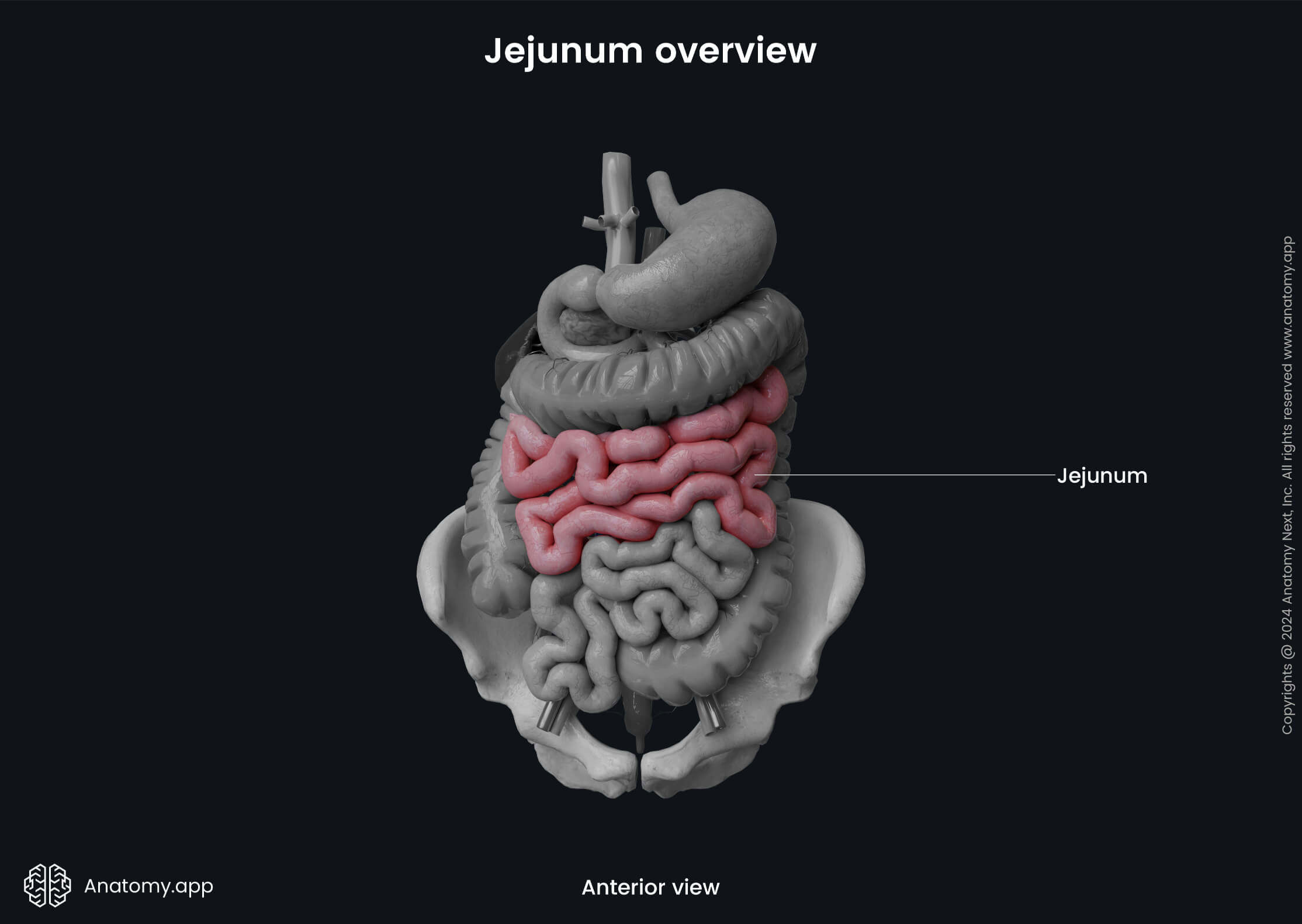

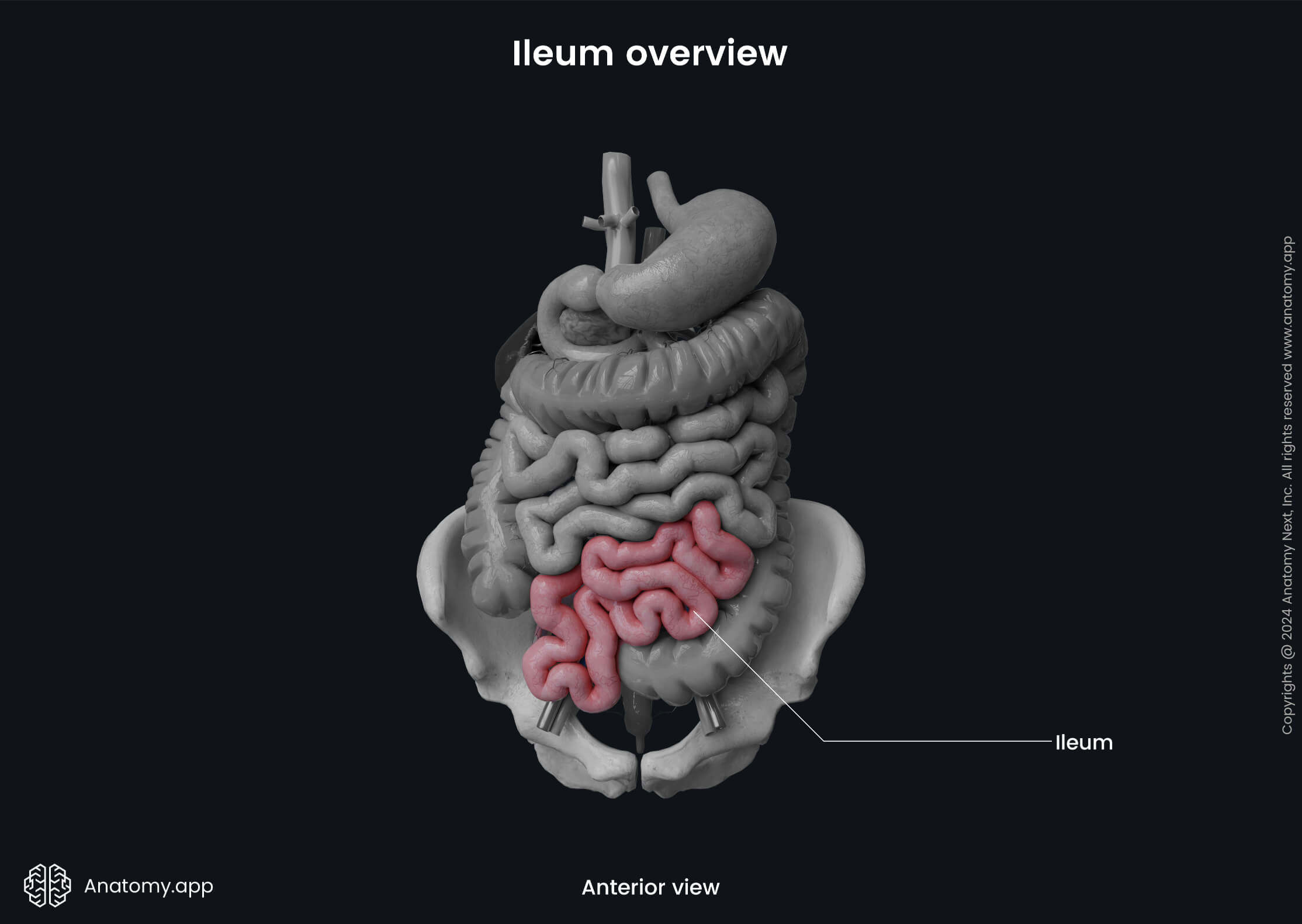

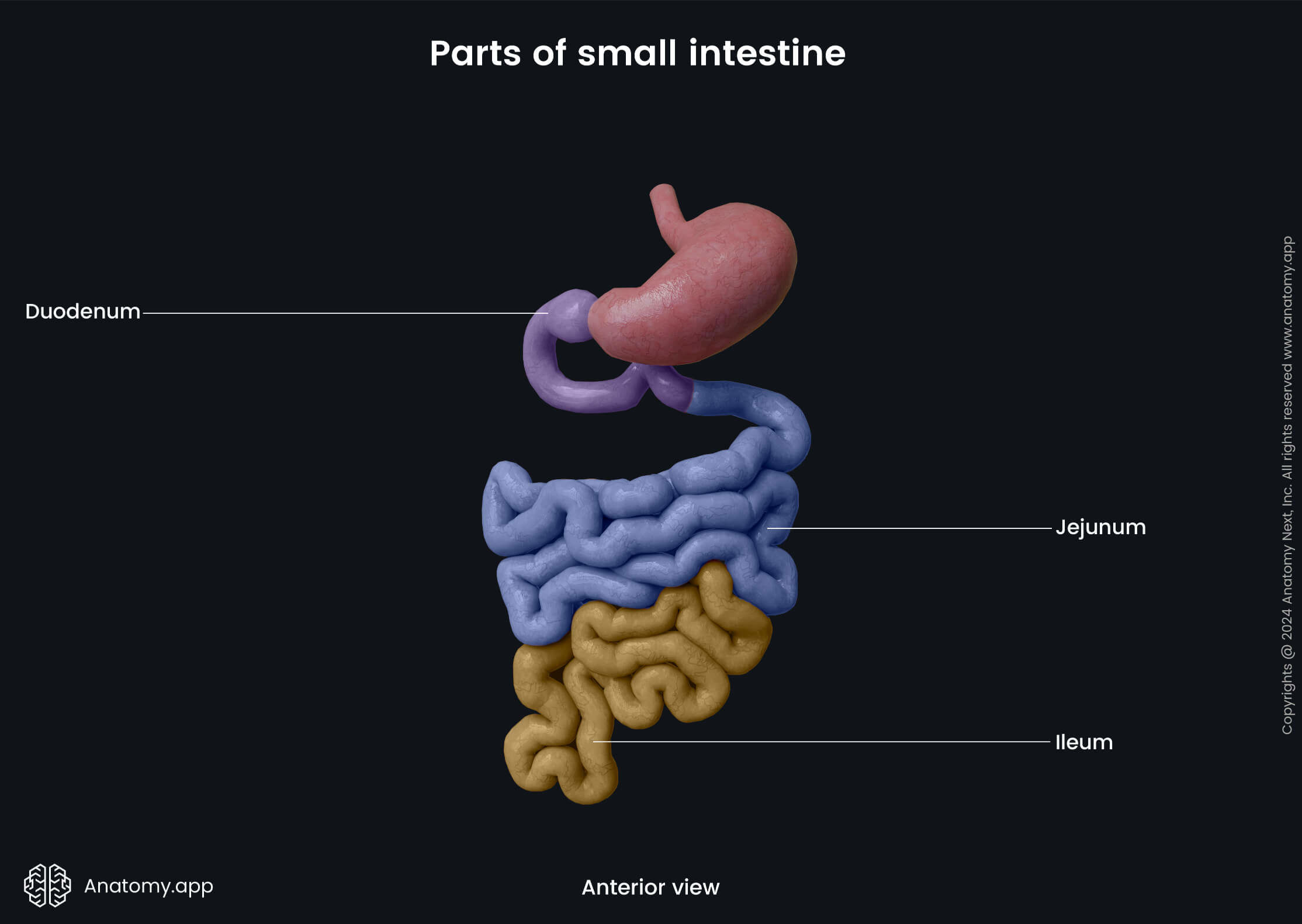

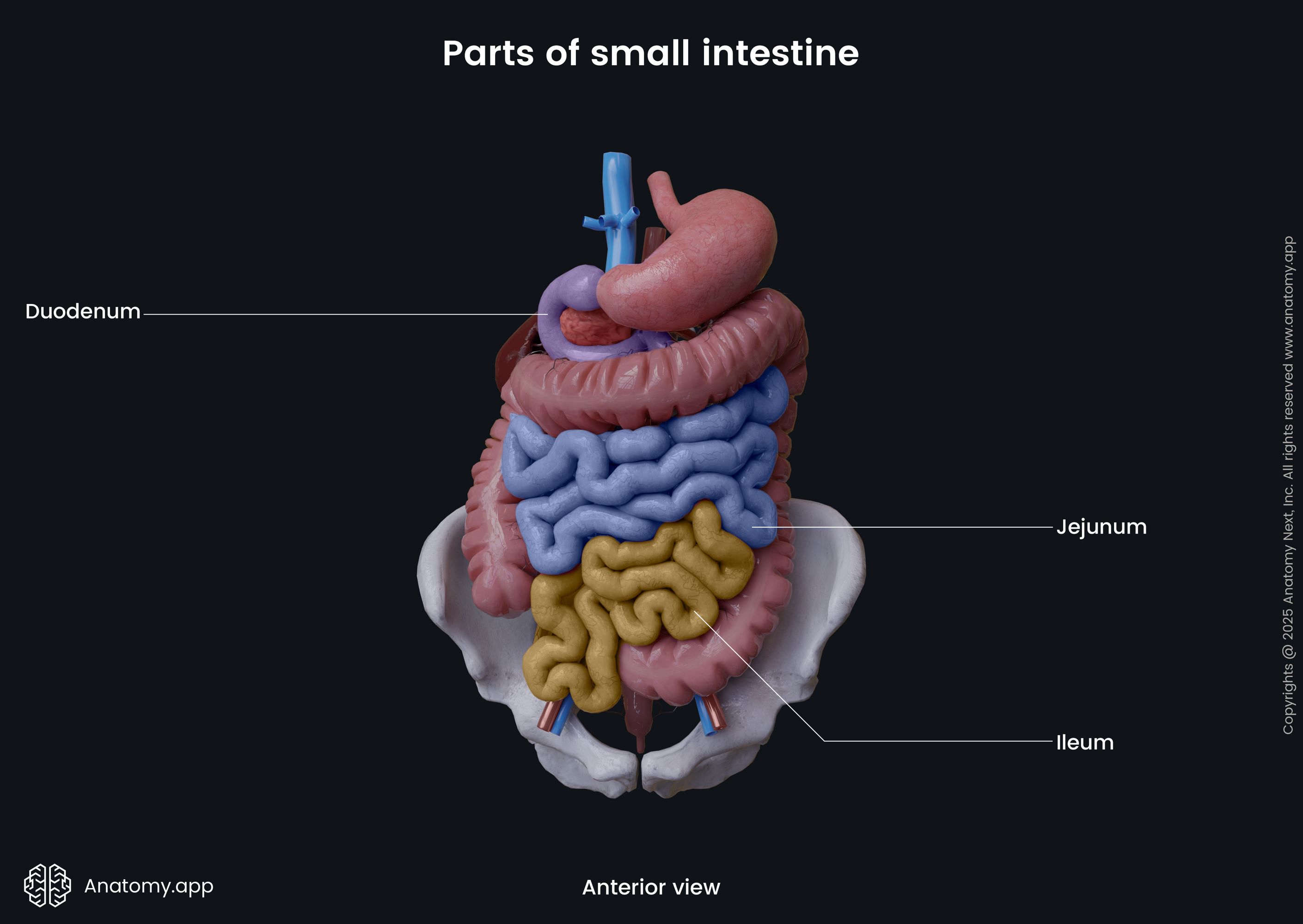

The jejunum and ileum (Latin: jejunum et ileum) are the middle and final portions of the small intestine. They are located in the abdominal cavity with the loops of the ileum also extending into the pelvic cavity. The jejunum and ileum are parts of the gastrointestinal tract between the first portion of the small intestine, called the duodenum, and the initial part of the large intestine, known as the cecum. The jejunum and ileum provide further digestion and nutrient breakdown of the digested food coming from the duodenum. They are also responsible for the absorption of nutrients and water needed for the normal functioning of the human body.

Jejunum and ileum anatomy

The loops of the jejunum are situated more in the middle area of the abdomen (umbilical region) and on the left side (left lateral region). The ileum is positioned in the lower abdominal area and more on the right side (right lateral, right inguinal and hypogastric regions). The loops of the ileum also extend in the pelvis. The jejunum extends between the duodenum and the ileum. But the ileum - connect the jejunum to the cecum.

The jejunum forms around two-fifths, while the ileum is three-fifths of the total length of the small intestine. The small intestine is around can measure up to 20 - 23 feet (around 6 - 7 m). The jejunum is around 8 feet (2.5 m), but the ileum - approximately 11 feet (3.5 m) long. Therefore, the ileum is the longest part of the small intestine. The narrowest portions of the small intestine can be found at the terminal part of the ileum.

The jejunum begins at the duodenojejunal flexure that projects at the level of the second lumbar vertebra (L2). The transition zone between the ileum and jejunum is not very well demarcated. However, the jejunum and ileum do not look the same, and knowing the differences between them, makes it easier to distinguish both parts. The ileum ends at the ileocecal junction with the ileocecal orifice and valve in the right iliac fossa.

The ileocecal valve demarcates the transition zone between the small and large intestines. The ileocecal valve is a functional valve that prevents the intestinal content backflow from the large intestine into the small intestine. But it can not control movements from the ileum to the cecum. The ileocecal valve is made up of the circular muscle fibers of the cecum and ileum.

The mesentery with its root attaches the ileum and jejunum to the posterior wall of the abdominal cavity along an oblique line. The oblique line starts from the left side of the second lumbar vertebra (L2), crosses the spine and ends in the right iliac fossa.

Differences between jejunum and ileum

As previously mentioned, the transition zone between the jejunum and ileum is not very well-demarcated and expressed. However, both parts have slightly different appearances.

- The jejunum is broader and better perfused with thicker intestinal walls. Therefore, it is more red than pink in color. The diameter of the ileum is smaller, the walls are thinner, and it looks much paler and pinker.

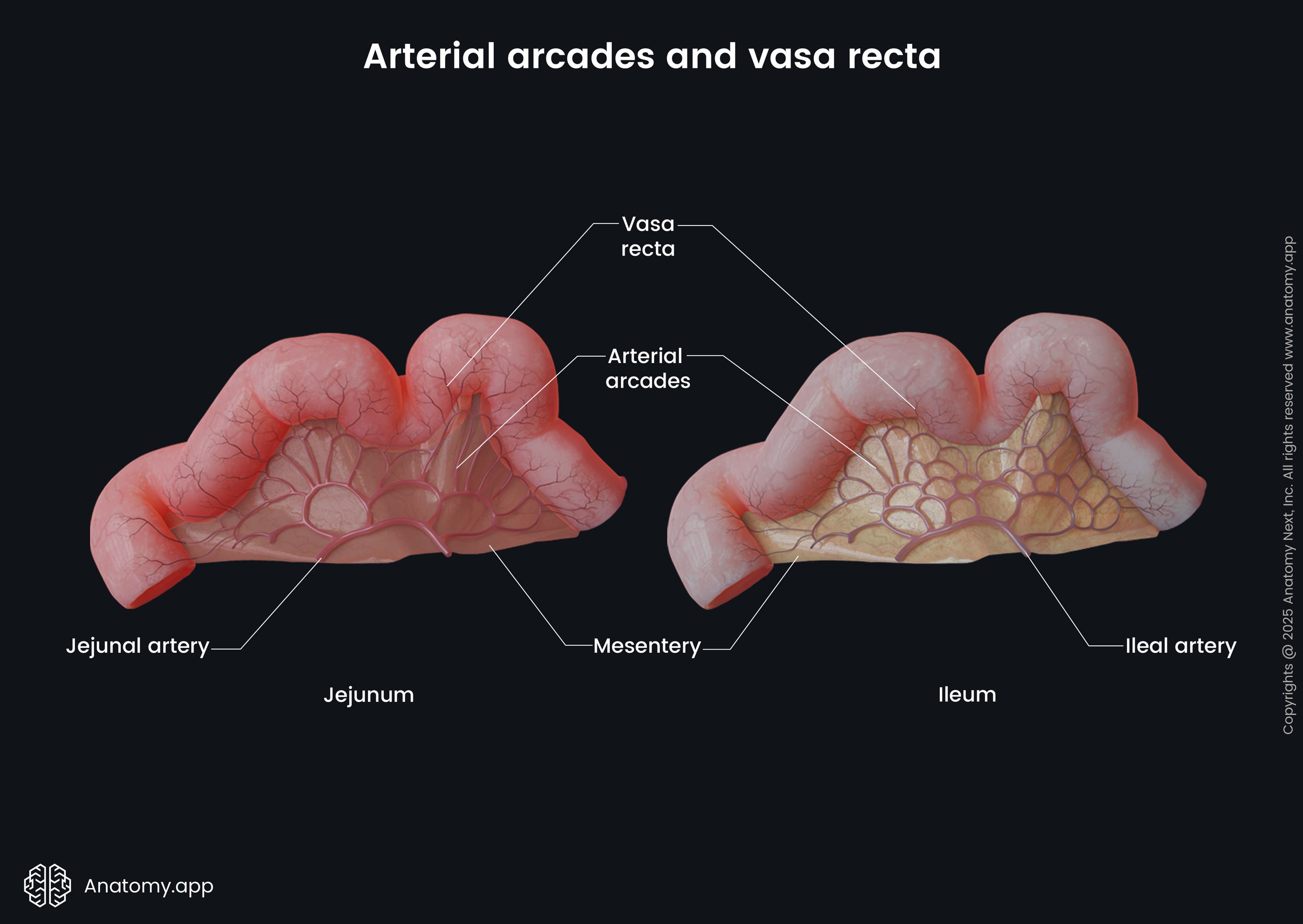

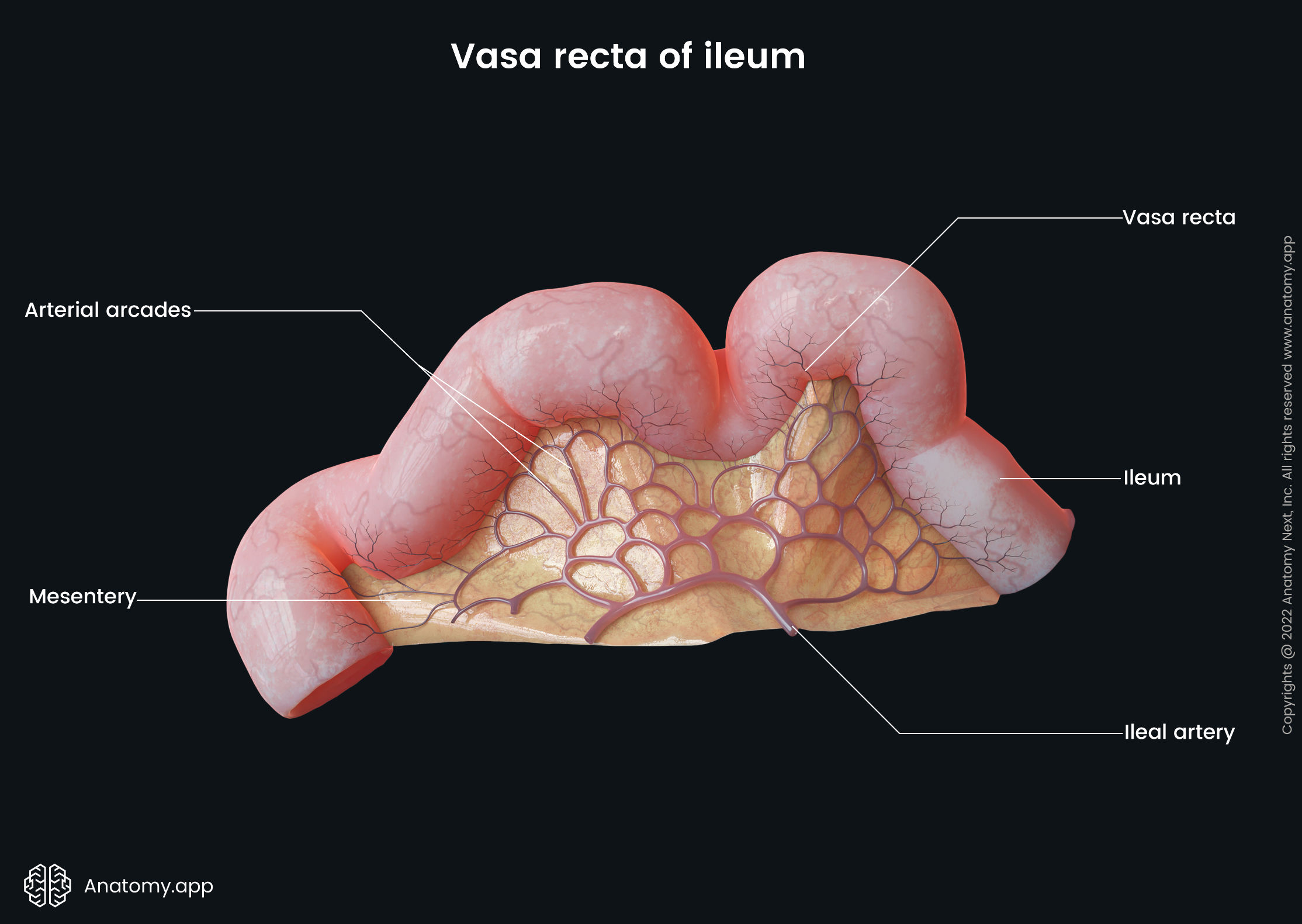

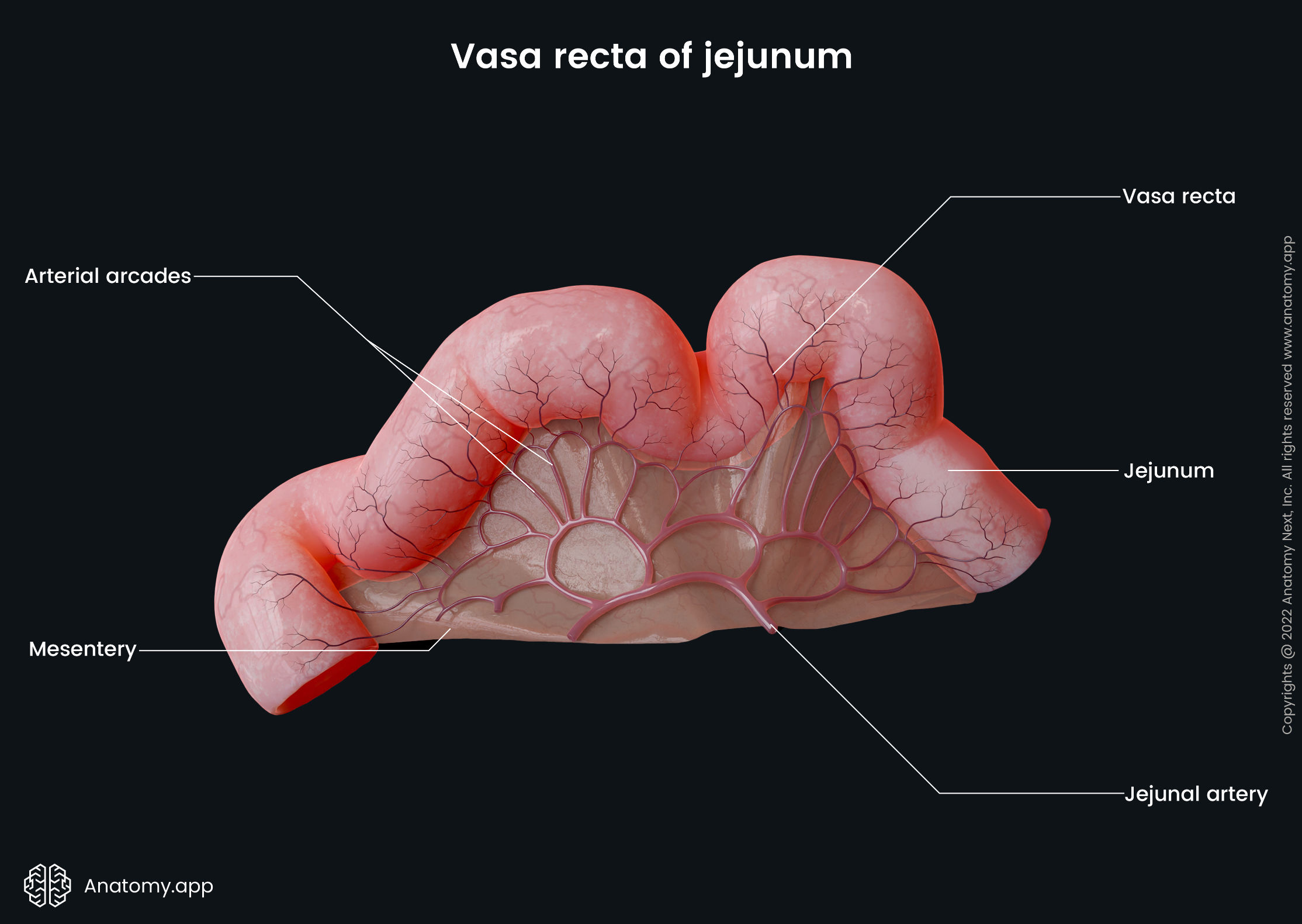

- The jejunum has fewer arterial loops, but they appear more significant than those of the ileum. The arterial arcades of the jejunum are simpler. The vasa recta of the jejunum are longer and lesser in number.

- The mesentery of the jejunum contains less fat, and it appears semi-translucent or transparent between the vasa recta. This characteristic is the reason why the mesentery of the jejunum between the vasa recta is called the peritoneal window. The ileum does NOT contain the mentioned window, and its mesentery is opaque.

Anatomical relations

The jejunum and ileum are surrounded by the large intestine from almost all sides.

- Posterior to the jejunum and ileum are located the organs of the retroperitoneal space.

- The anterior aspect of the intestines is covered by the greater omentum.

- The loops of the jejunum and ileum lie next to the ascending colon and cecum on the right side, but the loops on the left side connect with the descending colon and sigmoid colon.

- Superior to the jejunum and ileum are the transverse colon and mesocolon.

- And finally, inferior, the loops of the small intestine slip into the pelvis.

Jejunum and ileum histology

The walls of the jejunum and ileum are composed of four layers:

- Mucosa

- Submucosa

- Muscularis externa

- Serosa

Mucosa

The mucosa or mucosal layer faces the lumen of the small intestine and is in direct contact with its contents. It is composed of three sublayers:

- Epithelium

- Lamina propria

- Muscularis mucosae

The mucosa of the jejunum and ileum is lined by a simple columnar epithelium. The epithelium mainly consists of two types of cells - enterocytes and goblet cells. The enterocytes are columnar intestinal epithelial cells that primarily provide absorptive function. In contrast, the goblet cells produce and secrete mucus that helps to protect the intestine against pathogens and toxins. Also, mucus ensures lubrication and mechanical protection against intestinal contents. Besides epithelial and goblet cells, the epithelium also contains endocrine cells that produce hormones.

Beneath the epithelium is a layer called lamina propria. It is composed of loose connective tissue that supports the epithelial cells. The lamina propria of the jejunum and ileum is highly vascular, and it contains many cells, such as the fibroblasts, macrophages, plasmocytes, lymphocytes and many others to follow.

Also, the lamina propria includes a network of lymphoid cell aggregates and tissue called MALT (mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue). MALT presents with lymphoid follicles containing B and T lymphocytes, as well as macrophages. The lymphoid tissue becomes more prominent and more in number towards the ileum. The mucosa of the ileum presents with large aggregated lymphoid follicles that are large enough to be visible to the naked eye, and they are called Peyer’s patches (NOTE: Peyer’s patches are found only in the ileum).

The muscularis mucosae is the muscular layer of the mucosa formed by the smooth muscle cells, and it is situated at the base of the mucosal layer. The mucosa of the small intestine forms finger-like projections called villi. The villi are essential structures as they significantly increase the absorption area of the intestinal wall. The intestinal villi are more numerous and larger in the jejunum, while the ileum has fewer and smaller villi. The apical ends of the enterocytes are covered by other projections - microvilli. The microvilli appear as small hair-like filaments that also increase the absorption area.

Together with the submucosal layer, the mucosa forms circular mucosal folds called the circular folds (or plicae circulares, or valves of Kerckring) that encircle the lumen of the small intestine and project into it. Like the villi and microvilli, the circular folds also increase the surface area of the small intestine, thus providing the digestion and absorption of nutrients more efficiently. The circular folds are more prominent in the proximal part of the small intestine, including the jejunum, but become progressively less pronounced distally and may even be absent in the terminal ileum.

Another unique characteristic of the intestinal architecture is the presence of the intestinal glands (also called intestinal crypts or crypts of Lieberkühn). They are located at the bases of two adjacent villi, and they appear as mucosal pits. These glands are simple tubular glands that contain enterocytes, Goblet cells, highly specialized Paneth cells (provide an immune response and produce antibacterial substances), epithelial stem cells and neuroendocrine cells (secreting, for example, cholecystokinin). Intestinal gland cells form an alkaline fluid that dilutes chyme, thus promoting absorption.

Note: Chyme is a thick semi-fluid mass of partly digested food that is mainly mixed with gastric juice and expelled by the stomach into the duodenum.

Submucosa

The submucosa (submucosal layer) is made of loose connective tissue, and it contains blood and lymph vessels and nerve fibers. Within the submucosa of the jejunum and ileum is located the submucosal nerve plexus, which is known as the Meissner’s plexus.

Muscularis externa

The muscularis externa (also called muscularis propria) lies beneath the submucosa, and it consists of two distinct smooth muscle layers. The inner layer is the circular layer, and the outer is the longitudinal layer. The muscularis externa is thicker in the proximal part of the small intestine, gradually becoming thinner towards its distal end. Between both layers is situated the myenteric nerve plexus - the Auerbach’s plexus.

Serosa

The serosa or serous membrane is the outermost layer of the intestinal wall and it is formed by the visceral peritoneum. The serosa is composed of two sublayers: mesothelium, which refers to the simple squamous epithelium, and loose connective tissue beneath it.

Neurovascular supply of jejunum and ileum

Arterial blood supply

The jejunum and ileum receive arterial blood supply from branches of the superior mesenteric artery. The superior mesenteric artery enters the mesentery of the small intestine and gives off numerous jejunal and ileal arteries. The jejunal and ileal arteries anastomose and form many arterial loops called the arcades.

The arterial arcades give off straight arteries that go within the mesentery towards the coils of the jejunum and ileum. These straight arteries are known as the vasa recta. Also, the terminal ileum receives arterial supply from another branch of the superior mesenteric artery - the ileocolic artery.

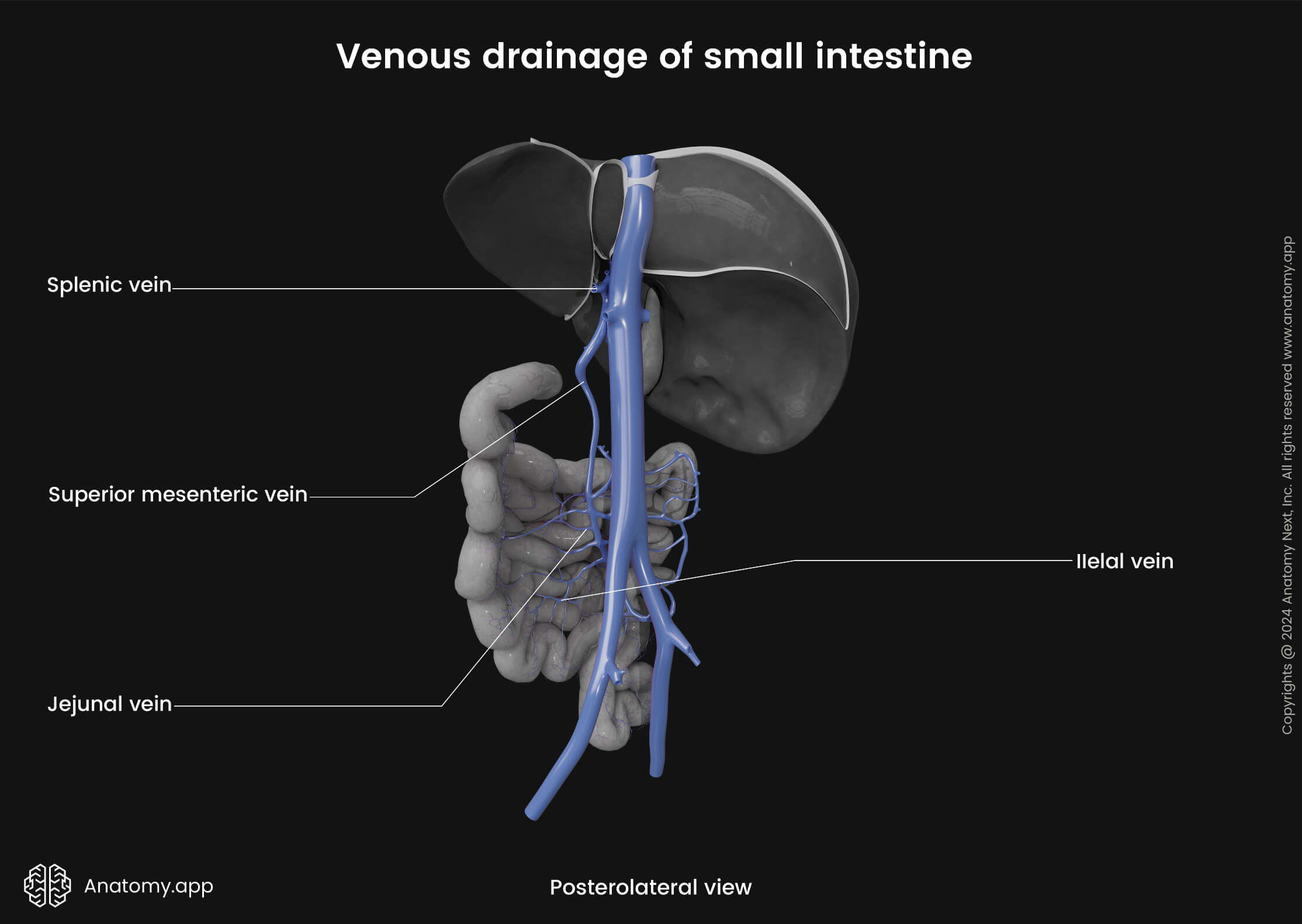

Venous drainage

The venous drainage of the jejunum and ileum occurs through small jejunal and ileal veins that carry blood to the superior mesenteric vein. After merging with the splenic vein behind the head of the pancreas, the superior mesenteric vein drains into the hepatic portal vein.

Innervation

The small intestine receives sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation. The sympathetic innervation of the jejunum and ileum occurs via the lesser thoracic splanchnic nerves that participate in the formation of the superior mesenteric plexus around the superior mesenteric artery and celiac plexus around the celiac trunk. The sympathetic fibers ensure vasoconstriction (narrowing of the lumen of blood vessels) of the intestinal blood vessels, relaxation of smooth muscle cells and inhibition of intestinal gland secretion.

The bodies of the preganglionic sympathetic neurons are located in the gray matter of the fifth to tenth thoracic segments (duodenum: T5 - T9, jejunum and ileum: T9 - T10) of the spinal cord. Axons of these neurons form the lesser thoracic splanchnic nerves that travel to the celiac and superior mesenteric plexuses and synapse there with the neurons of the celiac and superior mesenteric ganglia. Postganglionic axons then travel to the small intestine via the periarterial branches and supply it.

In contrast, the parasympathetic innervation of the jejunum and ileum is provided by fibers of the vagus nerve (CN X) via the anterior and posterior vagal trunks. The parasympathetic fibers stimulate intestinal gland secretion and smooth muscle cell contractions. Also, they provide vasodilation (widening of the lumen of vessels) of the intestinal blood vessels.

The nerve fibers of both systems extend throughout the entire length of the small intestine and synapse with the neurons located in the intestinal wall, forming two plexuses:

- Submucosal plexus (Meissner’s plexus) - located in the submucosal layer; contains only the parasympathetic fibers;

- Myenteric plexus (Auerbach’s plexus) - positioned in the muscularis externa between both its layers; contains parasympathetic and sympathetic nerve fibers.

Lymphatic drainage

The lymph from the jejunum and ileum is drained mainly to the juxta-intestinal and mesenteric lymph nodes located around the peripheral arterial arcades and jejunal and ileal arteries and then further to the superior mesenteric lymph nodes found around the superior mesenteric artery. The lymph collected from the terminal ileum usually is drained to the ileocolic lymph nodes.

Jejunum and ileum functions

The main functions of the jejunum and ileum include the absorption of nutrients (proteins, fats, carbohydrates, vitamins and minerals) and water from partially digested food and transportation of unabsorbed and waste products to the large intestine.

- Amino acids, small peptides and monosaccharides are absorbed in the bloodstream, but fats and fatty acids into the lymph and only partially into the bloodstream.

- The jejunum absorbs amino acids, fatty acids and sugars, fat-soluble vitamins (K, E, D, A), cholesterol, various microelements and other vitamins. It also absorbs significant amounts of water.

- The ileum absorbs the remaining nutrients that are unabsorbed by the jejunum. It absorbs vitamin B12 with the help of the stomach-produced intrinsic factor. The ileum also absorbs bile salts and acids.

- The small intestine contains lymphatic tissue aggregates (Peyer's patches) and Paneth cells that protect against various microbes and antigens. Mainly the ileum provides the immunological function as it has Peyer's patches.

References:

- Drake, R., Vogl, W., & Mitchell, A. (2019). Gray’s Anatomy for Students: With Student Consult Online Access (4th ed.). Elsevier.

- Gray, H., & Carter, H. (2021). Gray’s Anatomy (Leatherbound Classics) (Leatherbound Classic Collection) by F.R.S. Henry Gray (2011) Leather Bound (2010th Edition). Barnes & Noble.

- Moore, K.L., Dalley, A.F., Agur, A.M. (2018). Clinically Oriented Anatomy, 8th Edition, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Santaolalla, R., Fukata, M., & Abreu, M. T. (2011). Innate immunity in the small intestine. Current Opinion in Gastroenterology, 27(2), 125–131. https://doi.org/10.1097/mog.0b013e3283438dea