- Anatomical terminology

- Skeletal system

- Joints

- Muscles

- Head muscles

- Neck muscles

- Muscles of upper limb

- Thoracic muscles

- Muscles of back

- Muscles of lower limb

- Heart

- Blood vessels

- Lymphatic system

- Nervous system

- Respiratory system

- Digestive system

- Urinary system

- Female reproductive system

- Male reproductive system

- Endocrine glands

- Eye

- Ear

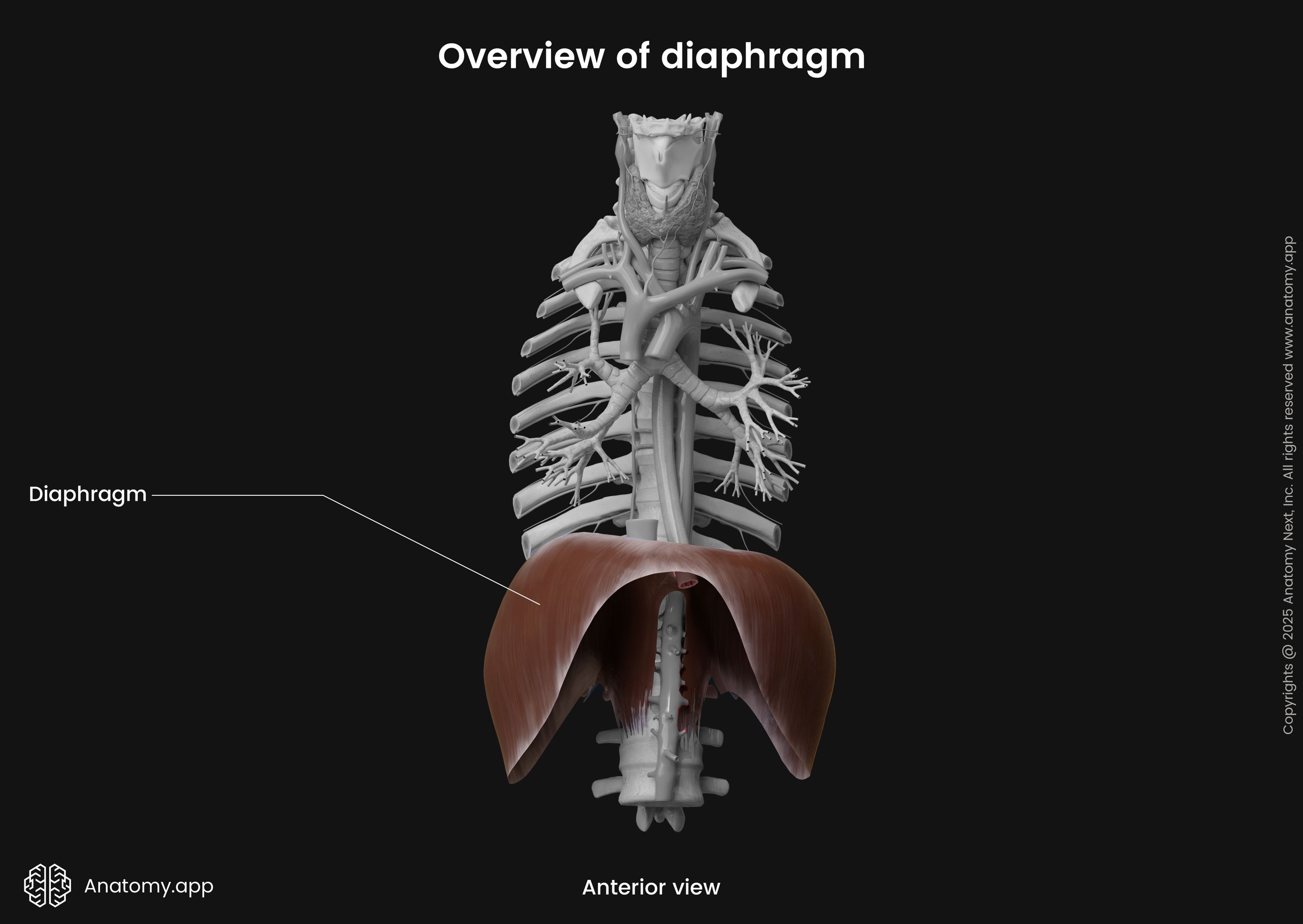

Diaphragm

The diaphragm (Latin: diaphragma), also called the respiratory diaphragm, is a thin, dome-shaped skeletal muscle. It is located within the inferior aspect of the rib cage. The diaphragm closes the inferior thoracic aperture, separating the thoracic cavity from the abdominal cavity. As a respiratory muscle, the primary function of the diaphragm is to provide breathing. Moreover, it is the main inspiration muscle.

| Diaphragm | ||

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Sternal part | Posterior surface of xiphoid process of sternum |

| Costal part | Internal surfaces of seventh (VII) to twelfth (XII) ribs and their respective cartilages | |

| Lumbar part | Right and left crura (lumbar vertebrae L1 - L3, their adjacent intervertebral discs, anterior longitudinal ligament) Medial and lateral arcuate ligaments | |

| Insertion | Central tendon | |

| Surfaces and relations | Superior (thoracic) surface | Heart Lungs |

| Inferior (abdominal) surface | Liver Stomach Spleen | |

| Openings | Major | Aortic hiatus Esophageal hiatus Caval foramen |

| Lesser | Lesser apertures in right crus Lesser apertures in left crus Openings behind medial arcuate ligaments Openings behind lateral arcuate ligaments Foramina of Morgagni Opening for left phrenic nerve | |

| Functions | Primary muscle of respiration Chief muscle of inspiration Muscle of abdominal straining (contributes to vomiting, defecation, urination and childbirth) Thoracoabdominal pump function | |

| Arterial blood supply | Subcostal and lower five intercostal arteries Pericardiacophrenic and musculophrenic arteries Superior and inferior phrenic arteries | |

| Venous drainage | Musculophrenic and pericardiacophrenic veins Superior and inferior phrenic veins | |

| Innervation | Motor | Phrenic nerves (C3, C4 and C5) |

| Sensory | Phrenic nerves (C3, C4 and C5) Lower six intercostal nerves | |

| Lymphatic drainage | Diaphragmatic lymph nodes ➝ Parasternal, posterior mediastinal, brachiocephalic lymph nodes | |

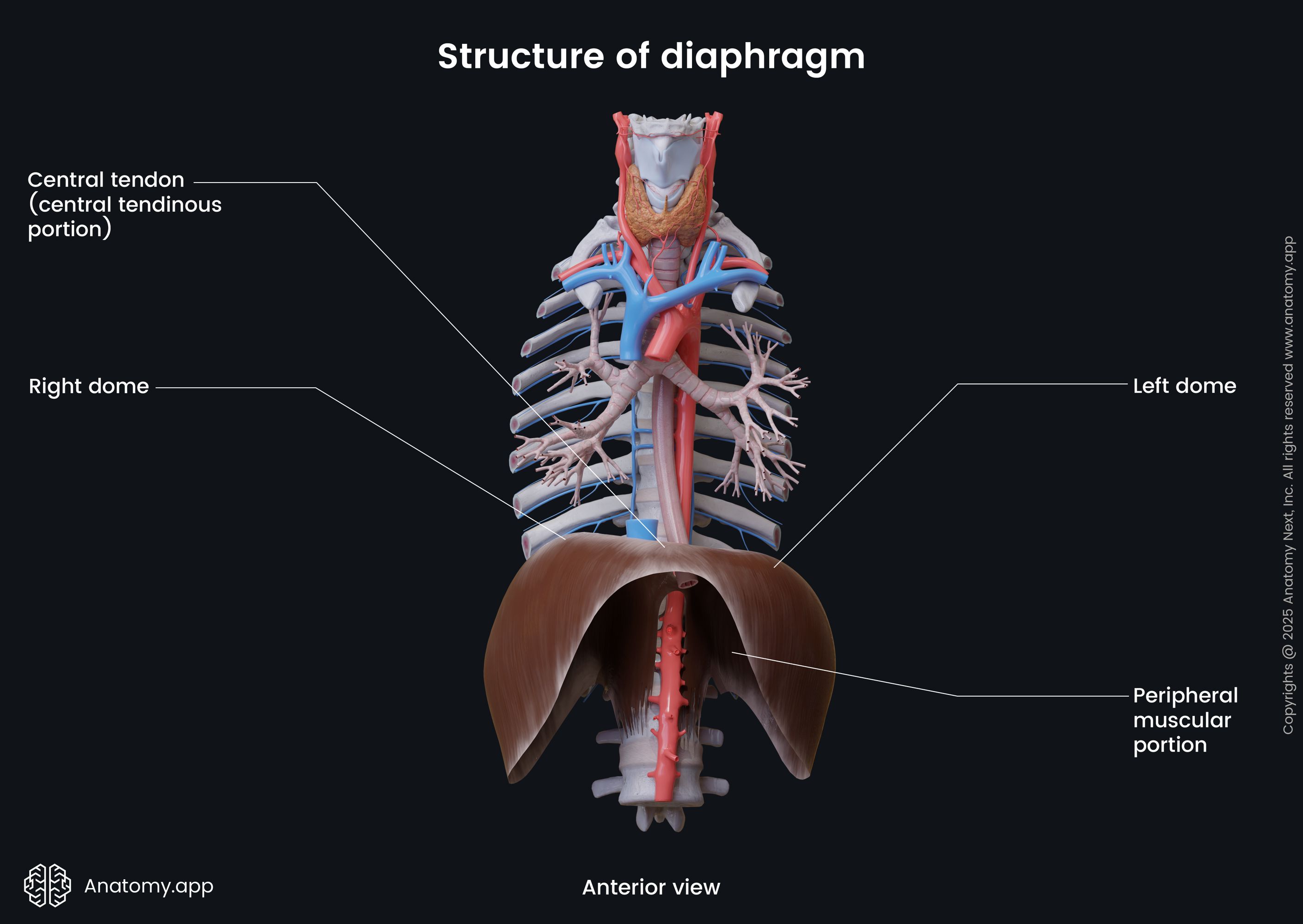

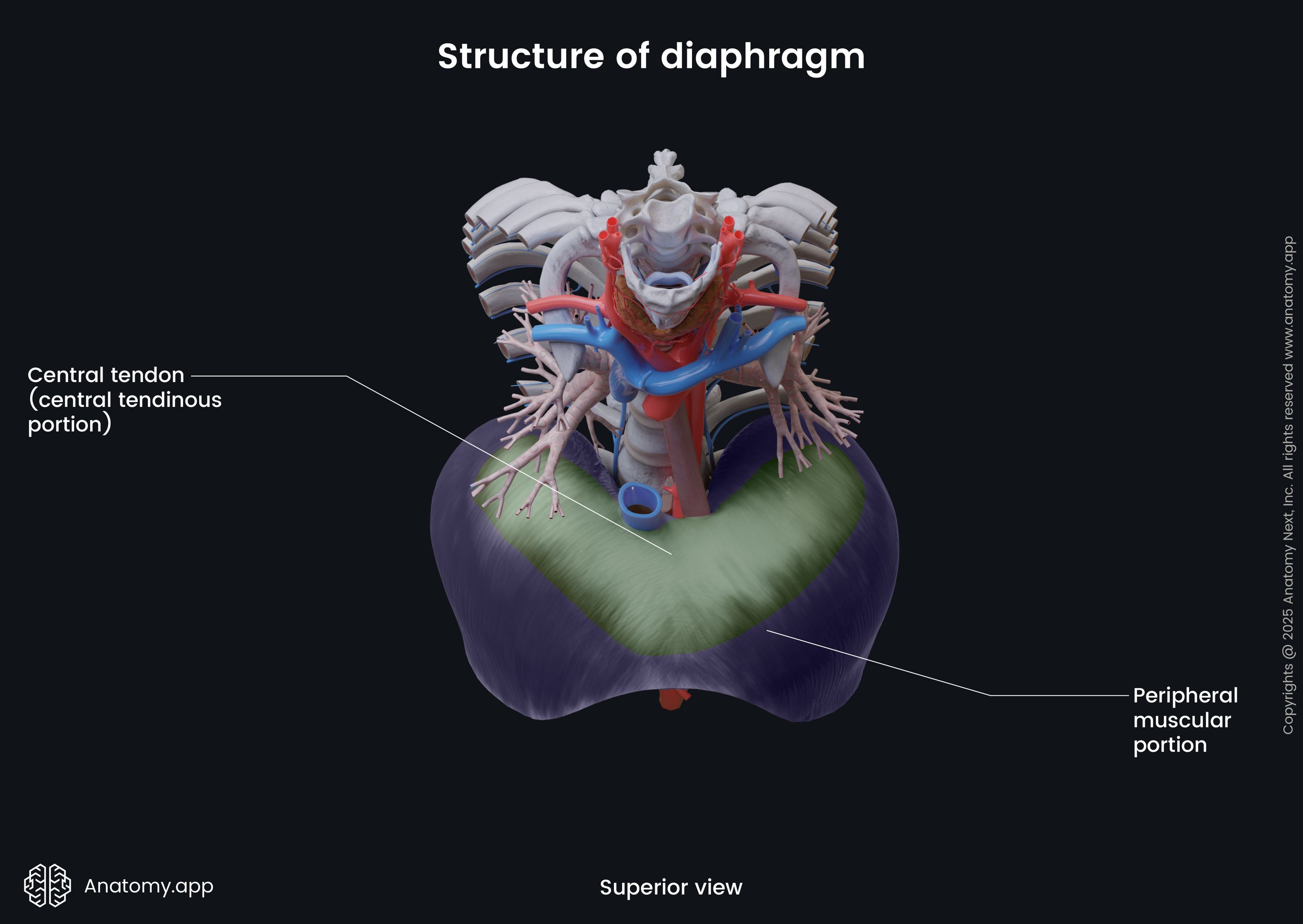

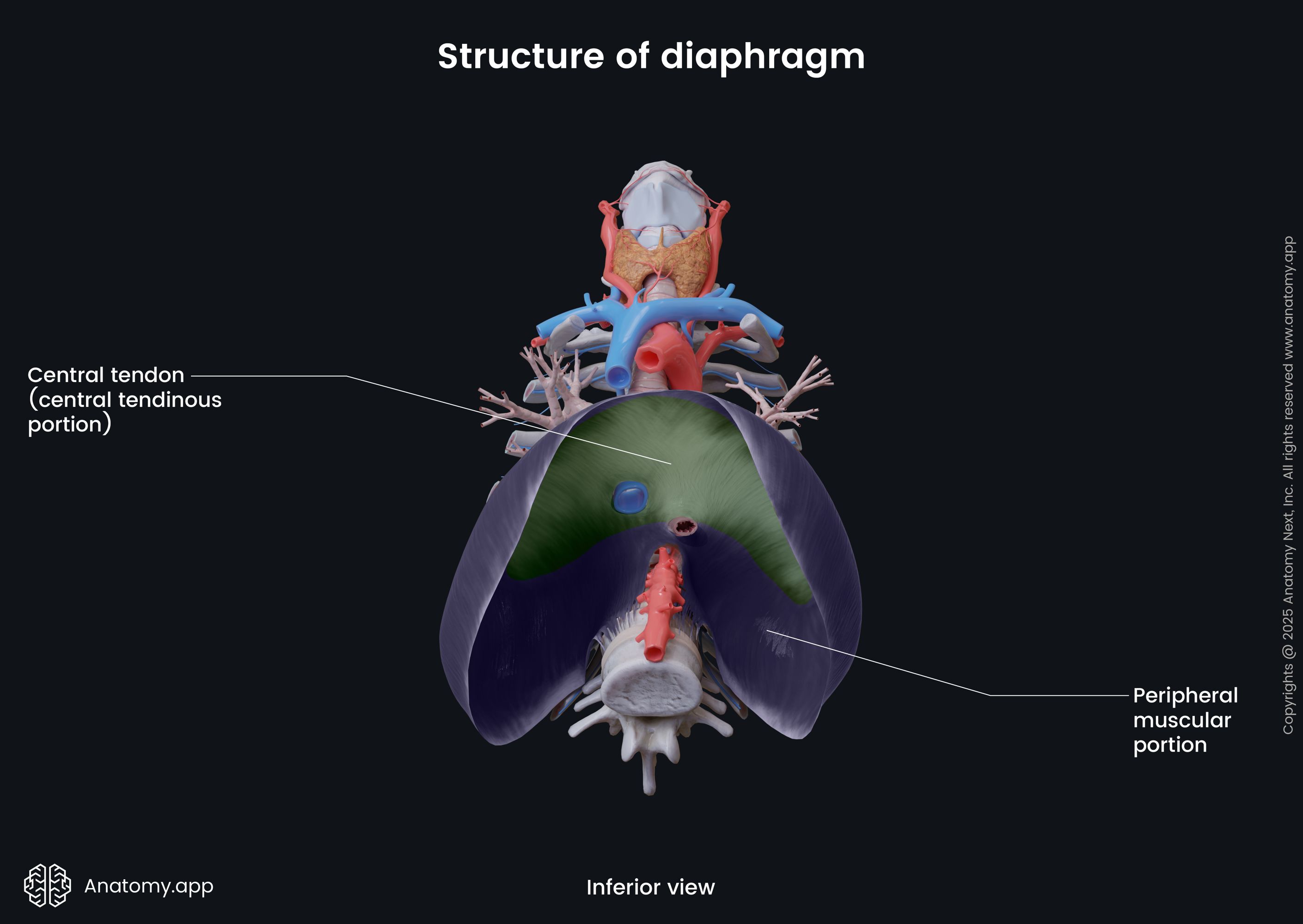

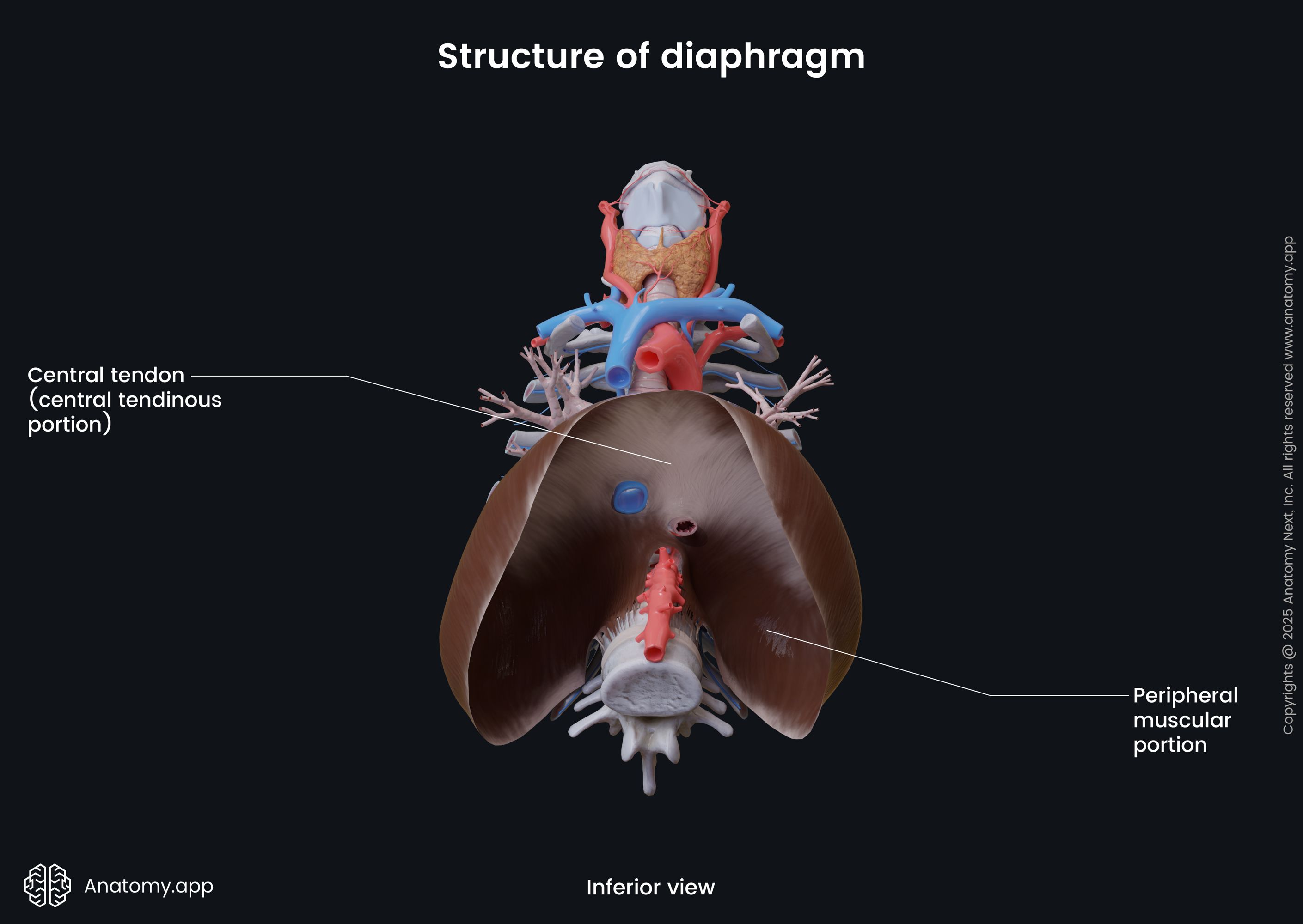

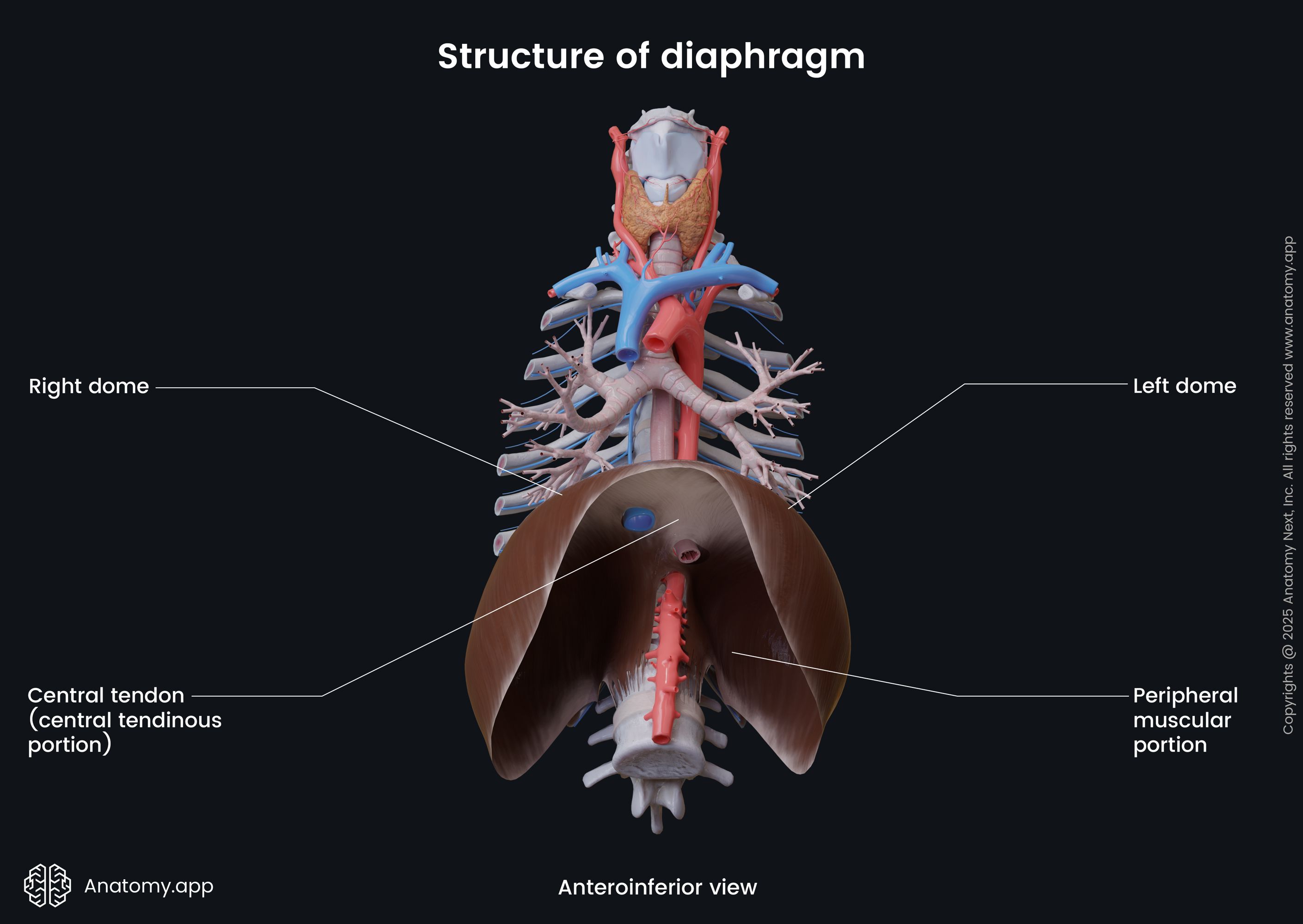

Structure of diaphragm

The diaphragm is a double-domed fibromuscular sheet with a right and a left dome. The right dome is situated higher than the left dome due to the liver located underneath it. The heart is positioned in the middle between both domes and forms a slight concavity on the superior surface of the diaphragm.

The diaphragm has two main components:

The muscular fibers originate from the periphery, attaching to the structures located along the inferior thoracic aperture. The muscular fibers then converge towards the center of the diaphragm to join the central tendon.

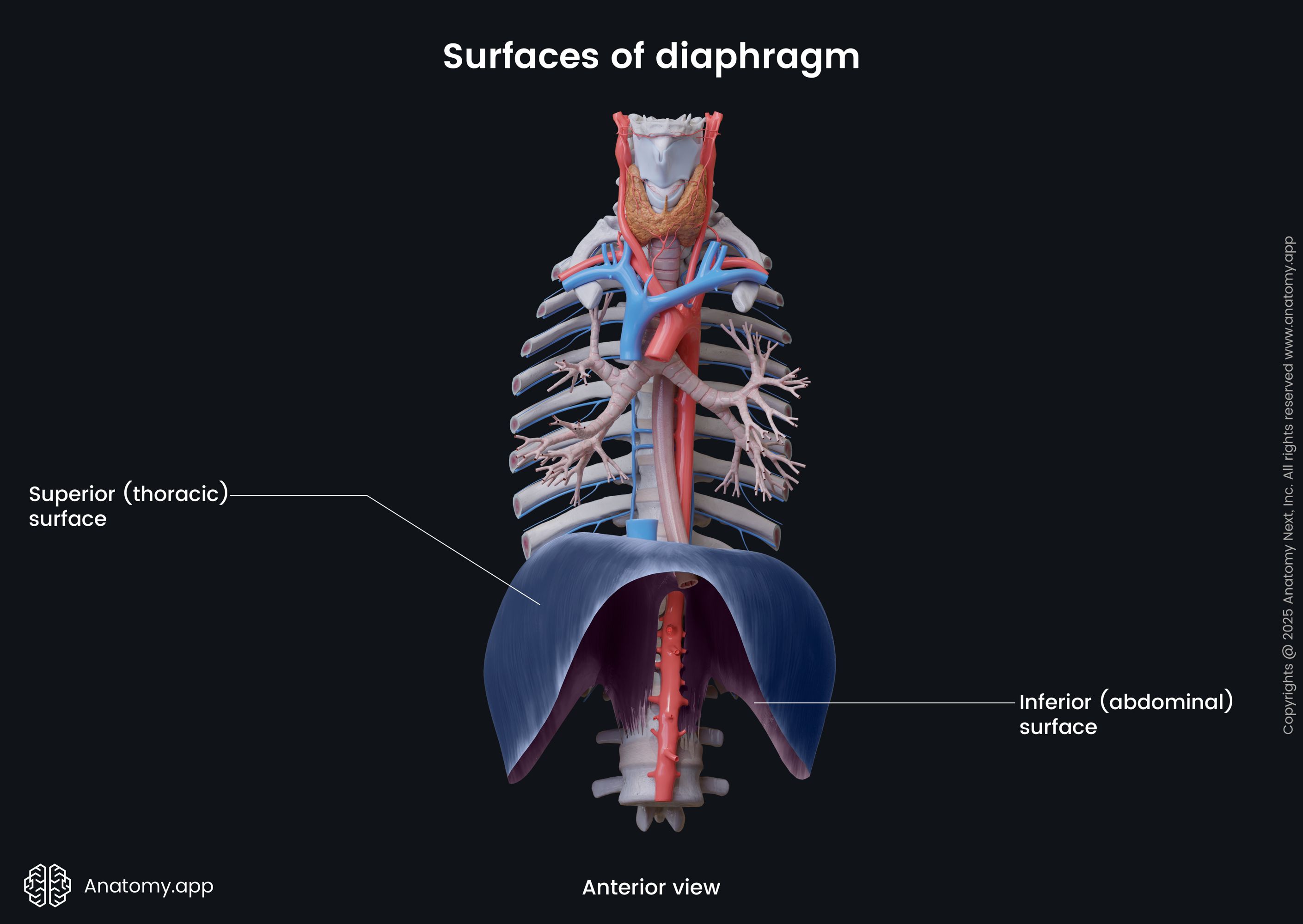

Surfaces of diaphragm and related structures

The diaphragm lies more or less in the transverse plane and faces two cavities - thoracic and abdominal. Therefore, it has two surfaces - superior or thoracic and inferior or abdominal. The word diaphragm actually comes from the Greek words dia, which means in between, and phragma, meaning fence.

The superior (thoracic) surface is convex and forms the floor of the thoracic cavity. It is covered by phrenicopleural fascia, which is a part of the endothoracic fascia. Above the phrenicopleural fascia is the diaphragmatic part of the parietal pleura, which surrounds the bases of the lungs. The only region of the diaphragm that does not connect with the pleura is its middle portion found below the heart. Here it is covered by the fibrous pericardium. Overall, the superior surface is related to the base of the heart and lungs.

The inferior (abdominal) surface of the diaphragm is concave and forms the roof of the abdominal cavity. It is covered by the peritoneum. Overall, the inferior surface of the diaphragm contacts the liver, stomach, and spleen.

Origin and insertion

The muscular portion of the diaphragm can be subdivided into three distinct parts:

- Sternal part

- Costal part

- Lumbar part

All three parts originate from different anatomical structures. The sternal part is the smallest and arises from the posterior surface of the xiphoid process of the sternum. The costal part is the largest and attaches to the internal surfaces of the seventh to twelfth ribs and their respective cartilages.

The lumbar part arises from two ligaments (medial and lateral arcuate ligaments) and two crura, which are, in turn, attached to the upper three lumbar vertebrae (L1 - L3), their adjacent intervertebral discs and the anterior longitudinal ligament. All muscular parts of the diaphragm insert into its central tendon.

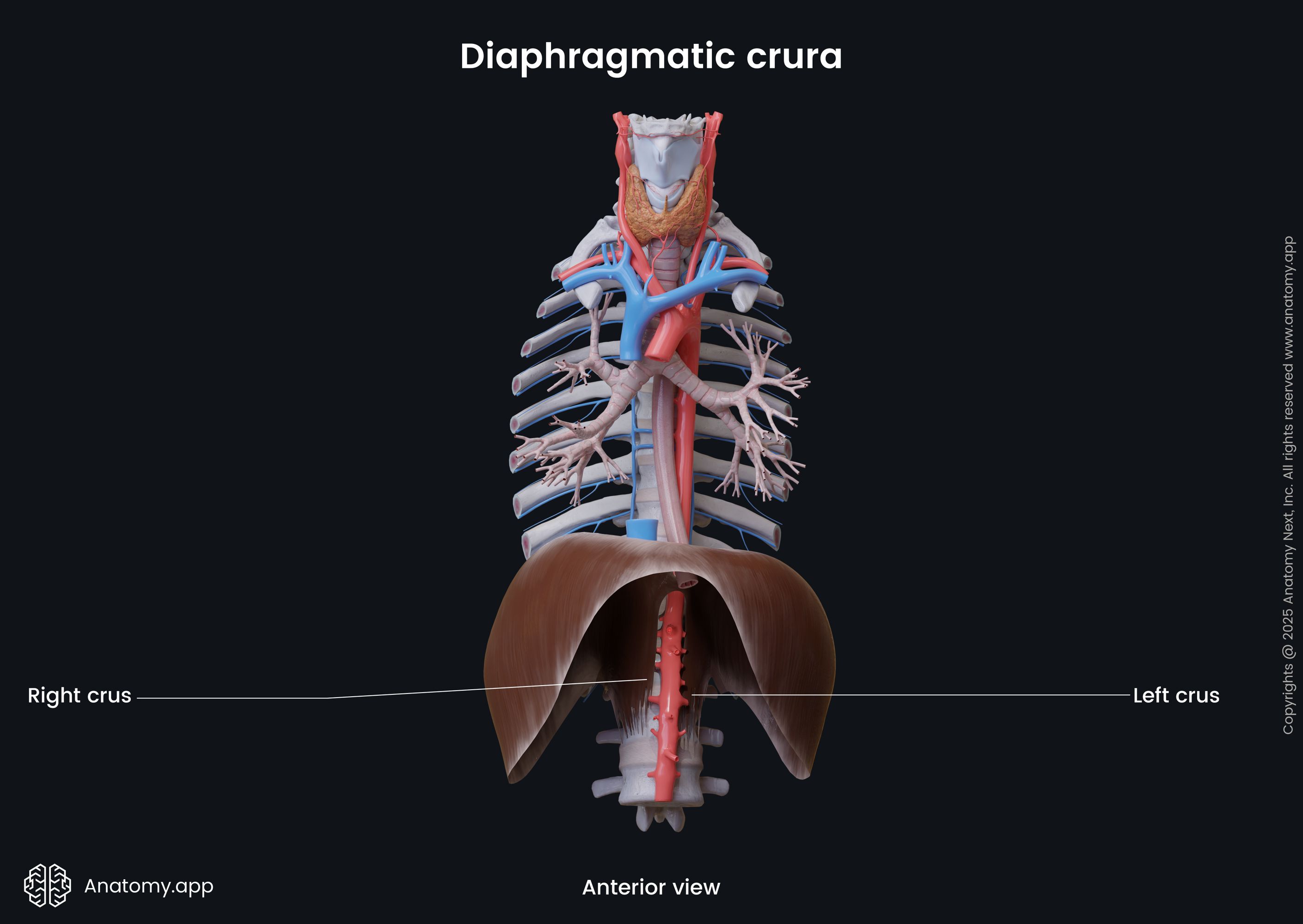

Diaphragmatic crura and ligaments

The diaphragm is attached to the lumbar vertebrae via two musculotendinous bands called the right and left diaphragmatic crura (sing. crus). The right crus is broader and longer. It originates from the anterior surfaces of the bodies of the upper three lumbar vertebrae (L1 - L3) and their respective intervertebral discs. The left crus attaches to the bodies of the upper two lumbar vertebrae (L1 - L2) and their associated intervertebral discs. Both crura are continuous with the anterior longitudinal ligament of the spine.

At the level of the twelfth thoracic vertebra (T12), the medial fibers of both crura join and form the median arcuate ligament. It is a tendinous arch located along the anterior aspect of the aortic hiatus and aorta. It does not allow the diameter of the opening to change during contractions of the diaphragm. Therefore, the blood flow within the aorta is not affected. The muscle fibers of both crura cross one more time, forming the esophageal hiatus at the level of the tenth thoracic vertebra (T10). These fibers act as a sphincter and assist in the prevention of stomach content backflow into the esophagus.

On either side of the median arcuate ligament are medial arcuate ligaments. The medial arcuate ligament is a tendinous arch in the fascia below the diaphragm that arches across the upper aspect of the psoas major muscle. It goes from the body of the first or second lumbar vertebra (L1/L2), passes over the psoas major muscle and attaches to the transverse process of the first lumbar vertebra (L1). Laterally it connects with the medial aspect of the lateral arcuate ligament.

The lateral arcuate ligament is also a tendinous arch in the fascia below the diaphragm, but it arches across the upper aspect of the quadratus lumborum muscle. It stretches between the transverse process of the first lumbar vertebra (L1) and the inferior margin of the twelfth rib.

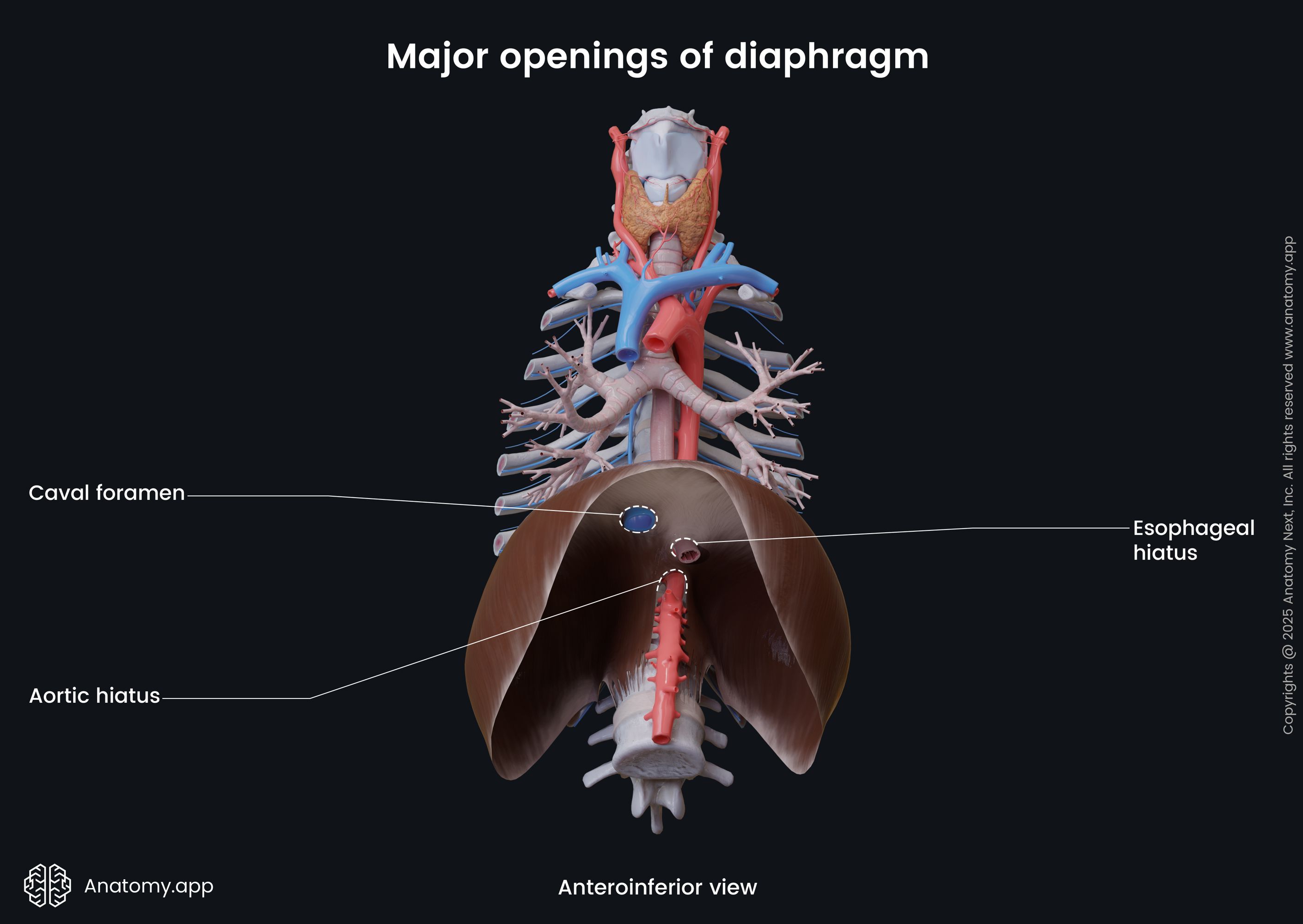

Diaphragmatic openings

Several anatomical structures pass through the diaphragm and travel between thoracic and abdominal cavities via various openings. The diaphragm has three major and several lesser openings.

Major openings of diaphragm

The major openings of the diaphragm include the following:

- Aortic hiatus

- Esophageal hiatus

- Caval foramen

The aortic opening, known as the aortic hiatus, is located within the posterior aspect of the diaphragm between the crura and the body of the twelfth thoracic vertebra (T12). Overall, the aortic hiatus is formed by the crura and median arcuate ligament. It transmits the thoracic aorta, thoracic duct, azygos vein and, occasionally, the hemiazygos vein. The opening borders with crura on its lateral sides, while the median arcuate ligament is anterior to it. The twelfth thoracic vertebra and the anterior longitudinal ligament lie posterior to the opening.

The esophageal hiatus is an opening that lies anterior and more on the left side of the aortic hiatus. It is usually located in the muscular part of the diaphragm near the right crus at the level of the tenth thoracic vertebra (T10). Overall, it is a formation of the right crus. The esophageal opening transmits the esophagus, anterior and posterior vagal trunks, esophageal branches of the left gastric vessels and lymphatics. The opening is slightly oblique and forms a short tunnel that accommodates the distal part of the esophagus.

The caval foramen (or caval opening, opening for inferior vena cava) is located in the central tendon at the level of the eighth thoracic vertebra (T8). The inferior vena cava and terminal branches of the right phrenic nerve travel through the caval opening. The inferior vena cava adheres to the margins of the opening, and it allows for an increase in the cardiac venous return during inspiration due to dilation of the opening and increased intra-abdominal pressure.

Lesser openings of diaphragm

There are also several smaller openings within the diaphragm known as the lesser openings, and they include the following:

- Lesser apertures in the right crus - several small openings that transmit the greater, lesser and least splanchnic nerves;

- Lesser apertures in the left crus - several small openings that serve as conduits for the greater, lesser and least splanchnic nerves and hemiazygos vein (occasionally);

- Openings behind the medial arcuate ligaments - transmit the sympathetic trunks;

- Openings behind the lateral arcuate ligaments - transmit the subcostal nerves and vessels;

- Foramina of Morgagni - two openings found within the connective tissue of the anterior aspect of the diaphragm between its sternal and costal parts; contain superior epigastric vessels;

- Opening for the left phrenic nerve - small opening that marks the site at which the left phrenic nerve pierces the dome of the left hemidiaphragm.

Functions of diaphragm

The diaphragm is the primary respiratory muscle and the main muscle of inspiration. Together with other principal muscles (intercostal muscles) and accessory muscles of respiration, including abdominal, thoracic and neck muscles, the diaphragm ensures breathing by expanding and compressing the thoracic cavity.

When the diaphragm contracts, its central part is pulled into the abdominal cavity. It makes the diaphragm flatten, increasing the vertical size of the thorax. The expansion of the thoracic cavity results in a decrease in intrathoracic pressure. The drop in the intrathoracic pressure creates a vacuum that allows the air from the atmosphere to get sucked into the lungs, and inhalation occurs.

When the diaphragm relaxes, it regains its dome-shaped appearance, and the volume of the thoracic cavity decreases. As a result, the intrathoracic pressure increases, which forces the air out of the lungs into the external environment, and exhalation happens.

The movements of the respiratory diaphragm also affect the muscles of the pelvic diaphragm (pelvic floor). When the respiratory diaphragm contracts and descends, the pelvic diaphragm also moves downward as a response to the changes in intra-abdominal pressure. These complementary changes ensure the support of the entire trunk and also assist in maintaining urinary continence during breathing and coughing.

As mentioned before, contractions of the diaphragm increase intra-abdominal pressure. Therefore, the diaphragm is also known as one of the muscles of abdominal straining. Together with the muscles of the anterolateral abdominal wall, it contributes to such functions as vomiting, defecation, micturition (urination) and parturition (childbirth).

Besides all the mentioned functions, the diaphragm has a thoracoabdominal pump function. When the intra-abdominal pressure increases, it compresses blood within the inferior vena cava and forces it to flow into the right atrium of the heart. Also, the exact same mechanism happens with the thoracic duct and lymph vessels located within the abdominal cavity.

Neurovascular supply of diaphragm

Arterial blood supply

The diaphragm is highly vascularized and receives arterial blood supply from the following arteries:

- Subcostal and lower five intercostal arteries

- Pericardiacophrenic and musculophrenic arteries

- Superior and inferior phrenic arteries

The subcostal arteries and lower five intercostal arteries supply the costal margins of the diaphragm. The pericardiacophrenic and musculophrenic arteries are derived from the internal thoracic artery and supply the thoracic surface of the diaphragm. Also, the superior phrenic arteries contribute to the arterial blood supply of the thoracic surface. They usually arise from either side of the descending thoracic aorta, just before it passes through the aortic hiatus, or from the tenth intercostal artery. The superior phrenic arteries form anastomoses with the pericardiacophrenic and musculophrenic arteries.

The inferior phrenic arteries are the main sources of arterial blood supply to the diaphragm. These arteries supply the diaphragm via its abdominal surface, and they most commonly originate from the celiac trunk or the abdominal aorta. The right inferior phrenic artery ascends posterior to the inferior vena cava and travels anteriorly along the right side of the caval foramen. The left inferior phrenic artery ascends posterior to the esophagus and passes anteriorly along the left side of the esophageal hiatus.

At the posterior aspect of the central tendon, the inferior phrenic arteries divide into medial and lateral branches. Each medial branch anastomoses with the medial branch of the opposite side, pericardiacophrenic and musculophrenic arteries. Each lateral branch of the inferior phrenic arteries reaches the thoracic wall, where it forms anastomoses with the musculophrenic and inferior posterior intercostal arteries.

Venous drainage

The main veins that provide venous drainage from the thoracic surface of the diaphragm are the musculophrenic and pericardiacophrenic veins that run along the corresponding arteries. These veins drain into the internal thoracic vein or directly into the brachiocephalic vein. Also, the thoracic surface is drained by the superior phrenic veins that further flow into the azygos vein.

The abdominal surface of the diaphragm is drained by the inferior phrenic veins. The right inferior phrenic vein further flows into the inferior vena cava, while the left phrenic vein divides into two branches. One of its branches drains into the left suprarenal or renal vein, while the other flows into the inferior vena cava.

Innervation

The diaphragm is innervated by the right and left phrenic nerves (C3, C4 and C5) that supply motor fibers to its muscular part. The phrenic nerves innervate the diaphragm via its abdominal surface. Also, these nerves provide sensory innervation to the central tendinous part of the diaphragm. Each phrenic nerve supplies the same (ipsilateral) side of the diaphragm.

The phrenic nerves mainly originate from the ventral rami of the fourth cervical spinal nerve (C4), with some contribution from the third and fifth cervical spinal nerves (C3, C5). Both phrenic nerves descend anterior to the lung roots within the thorax between the pericardium and mediastinal parietal pleura.

The sensory innervation to the periphery of the diaphragm is provided by the lower six or seven intercostal nerves.

Lymphatic drainage

The lymphatic drainage of the diaphragm occurs mostly through the diaphragmatic lymph nodes. They lie on the thoracic surface of the diaphragm and are divided into anterior, middle and posterior groups. Lymph from these nodes further drains into the parasternal, posterior mediastinal, and brachiocephalic lymph nodes.

References:

- Drake, R., Vogl, W., & Mitchell, A. (2019). Gray’s Anatomy for Students: With Student Consult Online Access (4th ed.). Elsevier.

- Gray, H., & Carter, H. (2021). Gray’s Anatomy (Leatherbound Classics) (Leatherbound Classic Collection) by F.R.S. Henry Gray (2011) Leather Bound (2010th Edition). Barnes & Noble.

- Moore, K.L., Dalley, A.F., Agur, A.M. (2018). Clinically Oriented Anatomy, 8th Edition, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.