- Anatomical terminology

- Skeletal system

- Joints

- Classification of joints

- Joints of skull

- Joints of spine

- Joints of lower limb

- Muscles

- Heart

- Blood vessels

- Lymphatic system

- Nervous system

- Respiratory system

- Digestive system

- Urinary system

- Female reproductive system

- Male reproductive system

- Endocrine glands

- Eye

- Ear

Atlanto-occipital joint

The atlanto-occipital joint (Latin: articulatio atlanto-occipitalis) is a paired articulation that connects the occipital bone of the skull with the cervical spine. It is a synovial ellipsoid-type joint. The atlanto-occipital junction belongs to a larger craniovertebral joint group, which includes two articulations found at the base of the skull between the occipital bone and the first two cervical vertebrae - the atlas (C1) and axis (C2). These junctions provide a relatively wide range of motion compared to other joints in the axial skeleton.

| Atlanto-occipital joint | |

|---|---|

| Classification | Synovial ellipsoid-type joint Diarthrosis |

Articulating structures | Superior articular facet of atlas Occipital condyle |

Ligaments | Nuchal ligament Alar ligaments Apical ligament of dens Anterior atlanto-occipital ligament (membrane) Posterior atlanto-occipital ligament (membrane) Tectorial membrane |

Arterial blood supply | Branches of deep cervical, vertebral and occipital arteries |

Venous drainage | Pharyngovertebral veins |

Lymphatic drainage | Retropharyngeal lymph nodes → upper deep cervical lymph nodes |

Innervation | Anterior ramus of first cervical spinal nerve (C1) |

Movements | Biaxial joint: Flexion and extension of head Limited lateral flexion and minimal rotation of head |

Classification of atlanto-occipital joint

Depending on the provided movement, the atlanto-occipital joint is classified as a diarthrosis. Diarthroses are joints with the widest range of motion. Based on the involved tissue, this articulation is a synovial joint. Synovial junctions can be further subdivided according to the type of movements they provide.

The atlanto-occipital articulation is ellipsoid (also called condyloid) in type. Ellipsoid joints are biaxial, meaning they move in two planes. They allow flexion/extension and abduction/adduction (movements in the lateral direction away from the midline of the body and back in the medial direction towards the midline). Ellipsoid-type joints are articulations between an oval-shaped convex condyle of one bone (in this case, occipital bone) and an elliptical, slightly concave cavity of another bone (atlas).

Synovial joints lack intervertebral discs, and the first two cervical vertebrae do not have uncinate processes. The articulating surfaces of the atlanto-occipital joints are lined by hyaline cartilage, and they are enclosed by a fibrous joint capsule. Within the joint is a synovial cavity. The joint cavity contains synovial fluid that acts as a lubricant and is produced by the cells in the synovial membrane. The joint is strengthened and stabilized by several ligaments that are positioned outside the joint capsule.

Note: To read more in detail about different joint types and their functions, please visit our article on the classification of joints.

Articulating structures of atlanto-occipital joint

The atlanto-occipital joint is an articulation at the base of the skull between articulating surfaces of the atlas (C1) and occipital bone. The atlas is the first cervical vertebra, and it directly connects with the skull base. Its articular facets are slightly concave and positioned on the superior aspects of the lateral masses. They are called the superior articular facets of the atlas. The articular surfaces of the occipital bone appear convex and are found on the occipital condyles.

Joint capsule

The articulating surfaces of the atlanto-occipital joint are enclosed by a fibrous joint capsule. However, it is very loose and thin, but these joints are very mobile. Therefore, the atlanto-occipital joints are primarily stabilized with ligaments. The joint capsule is attached to the margins of the articular surfaces.

Ligaments

The atlanto-occipital joints are stabilized and strengthened by several ligaments and membranes of the spine. They include the following:

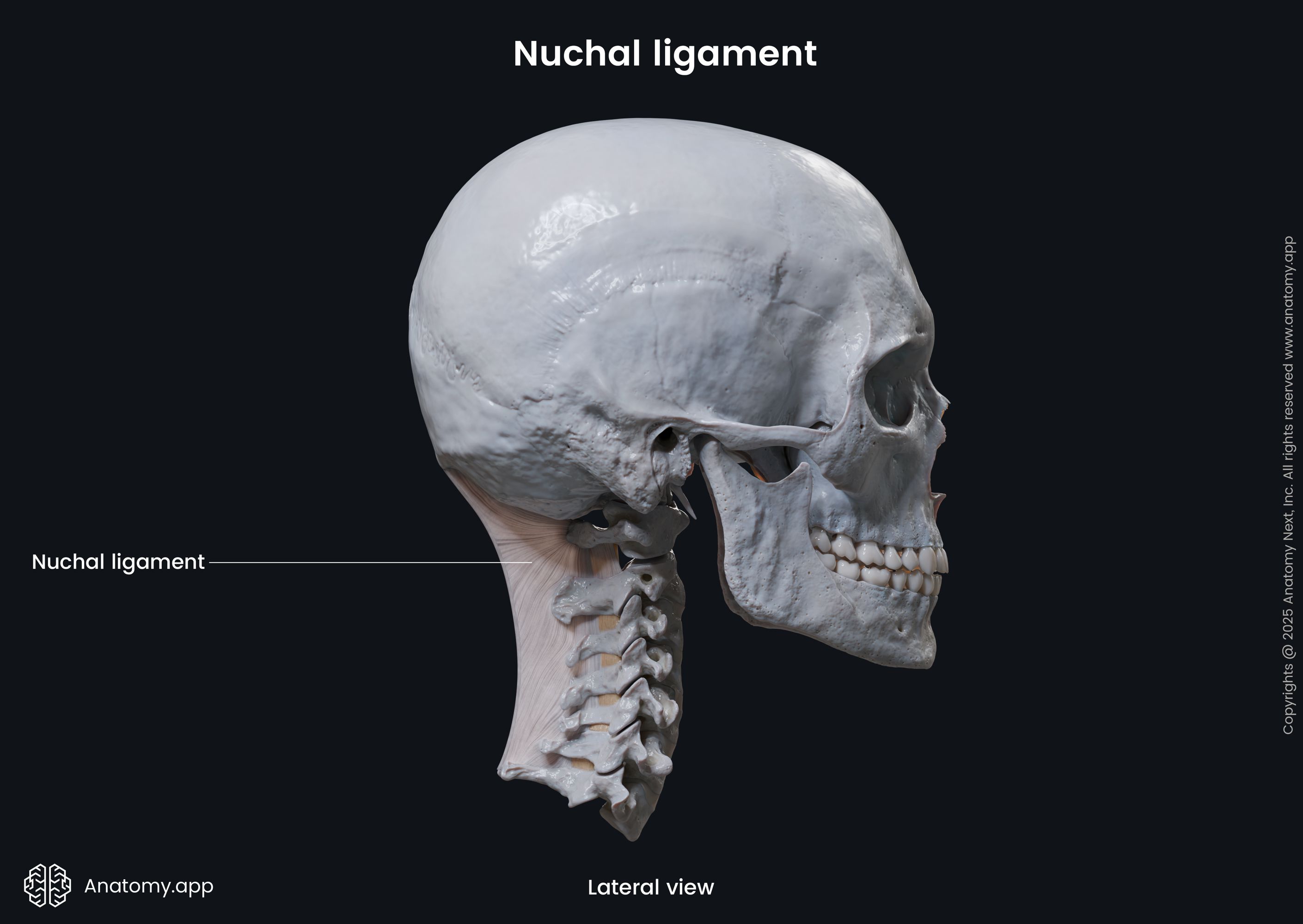

- Nuchal ligament

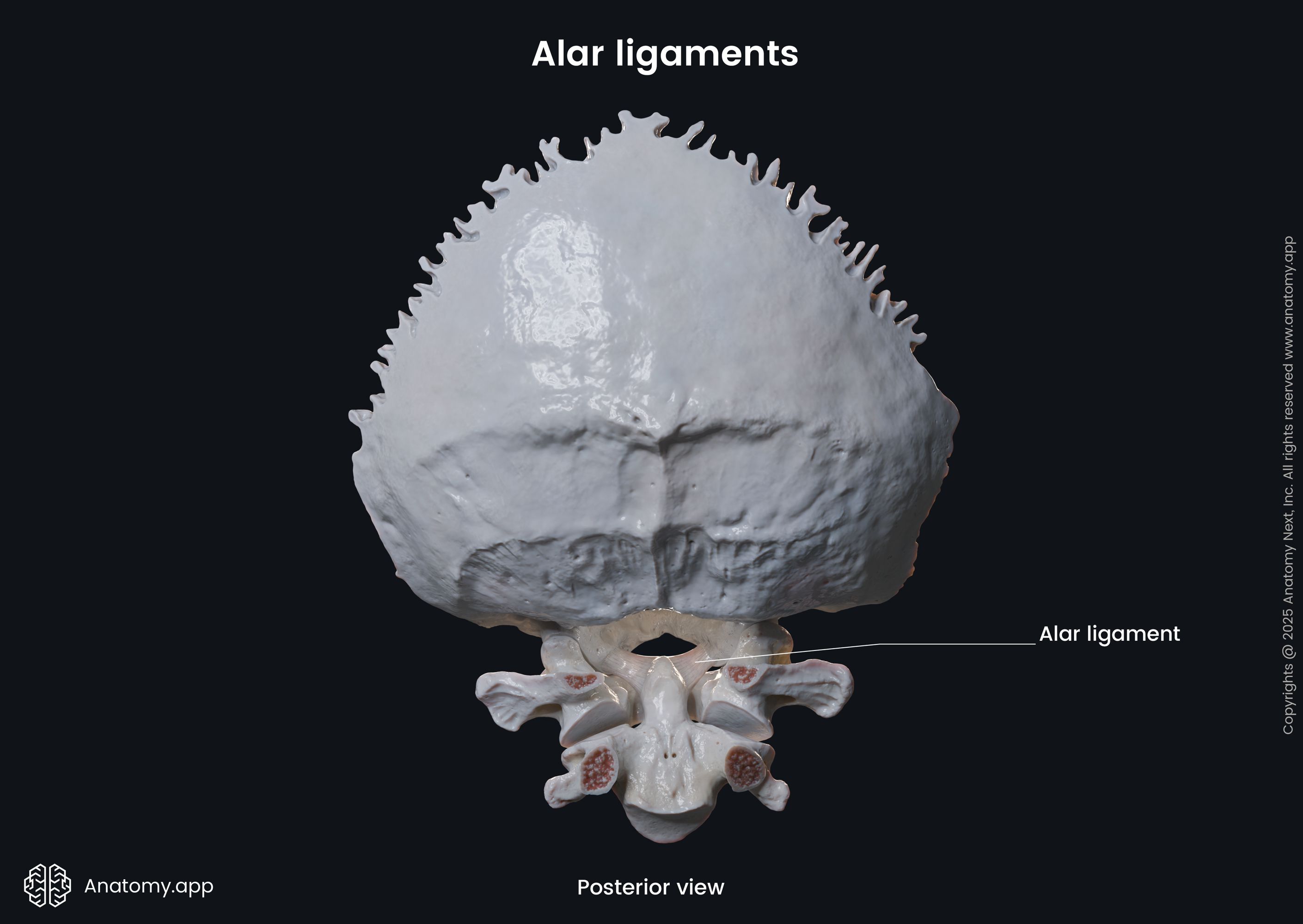

- Alar ligaments

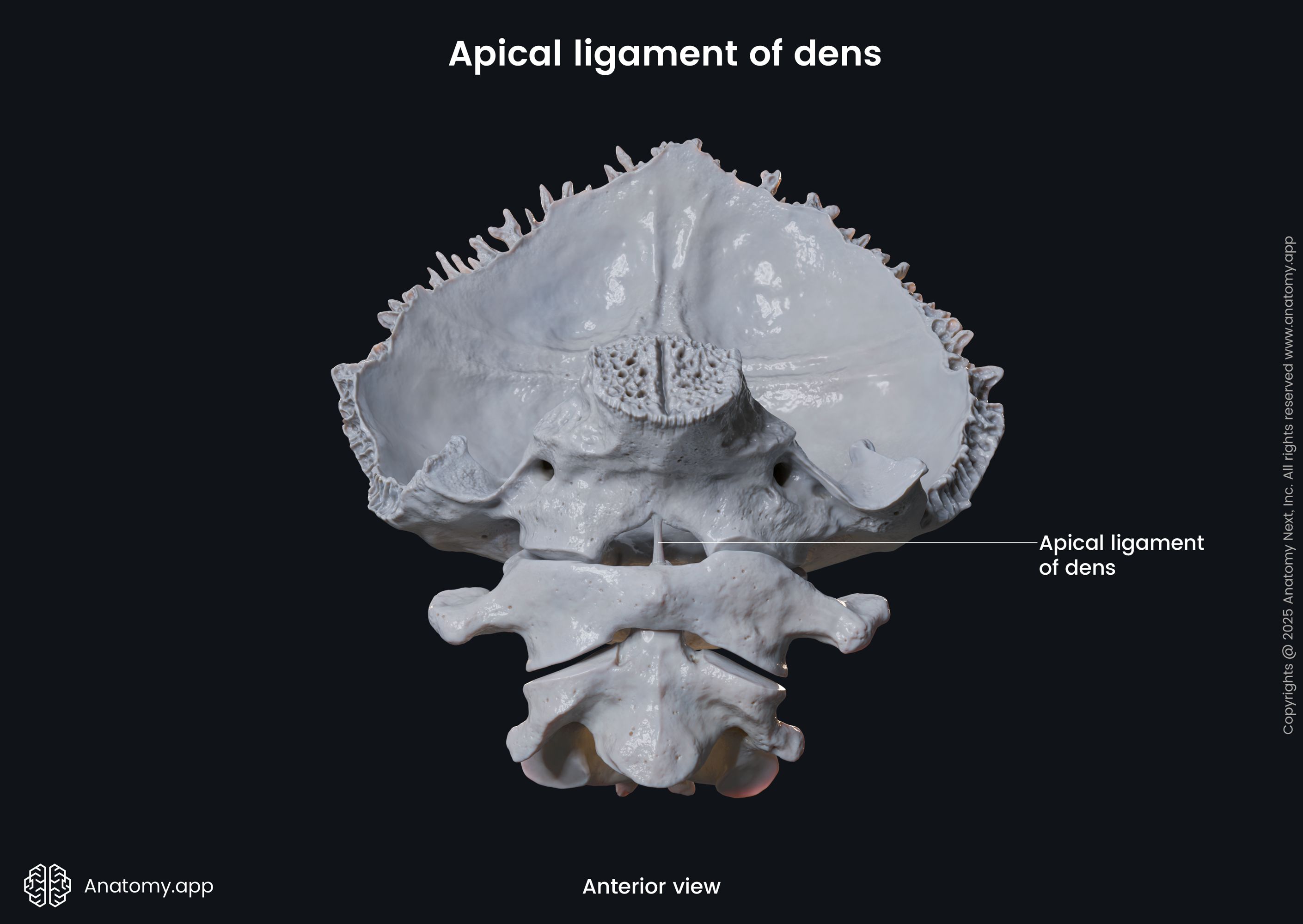

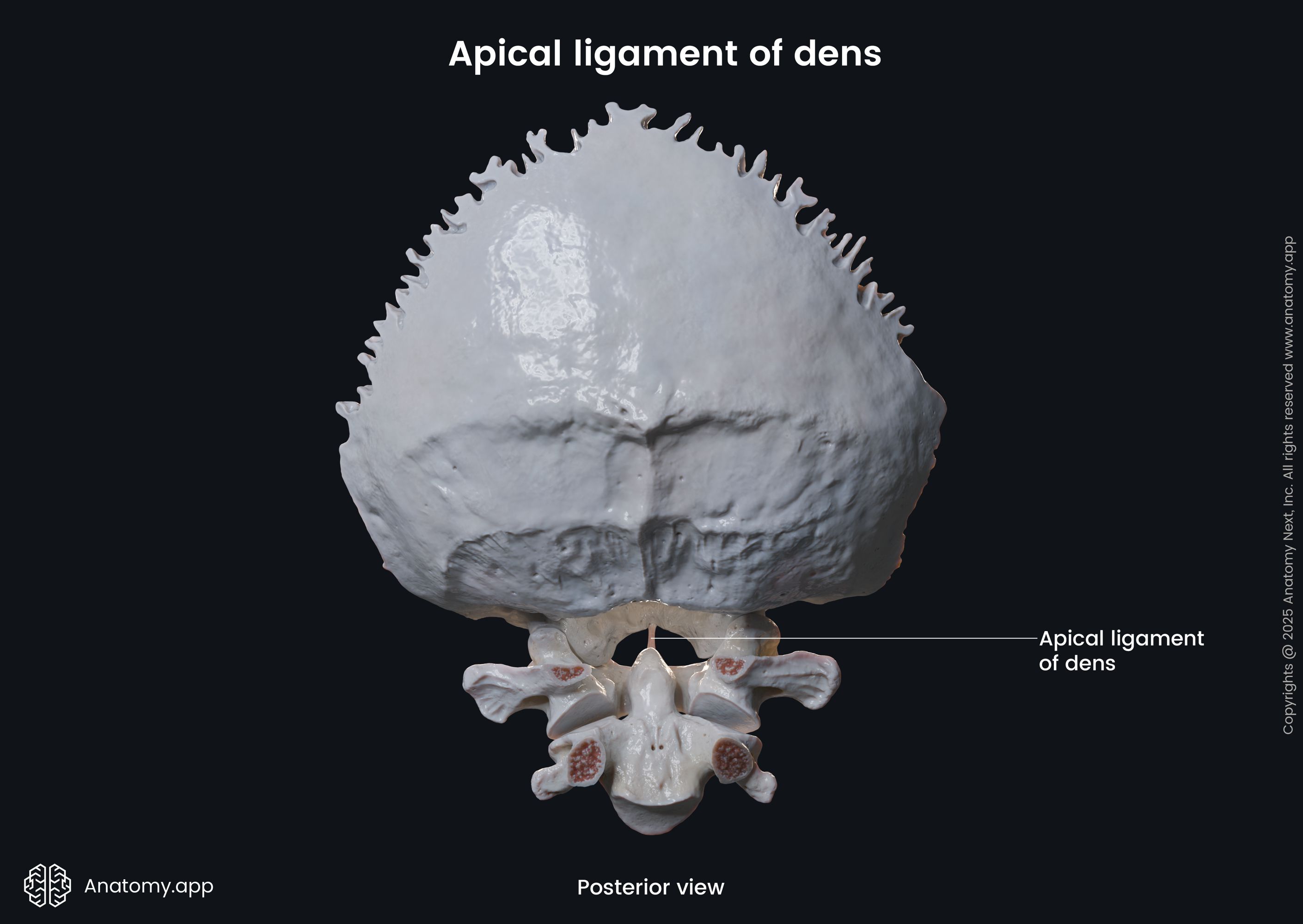

- Apical ligament of dens

- Anterior atlanto-occipital ligament (membrane)

- Posterior atlanto-occipital ligament (membrane)

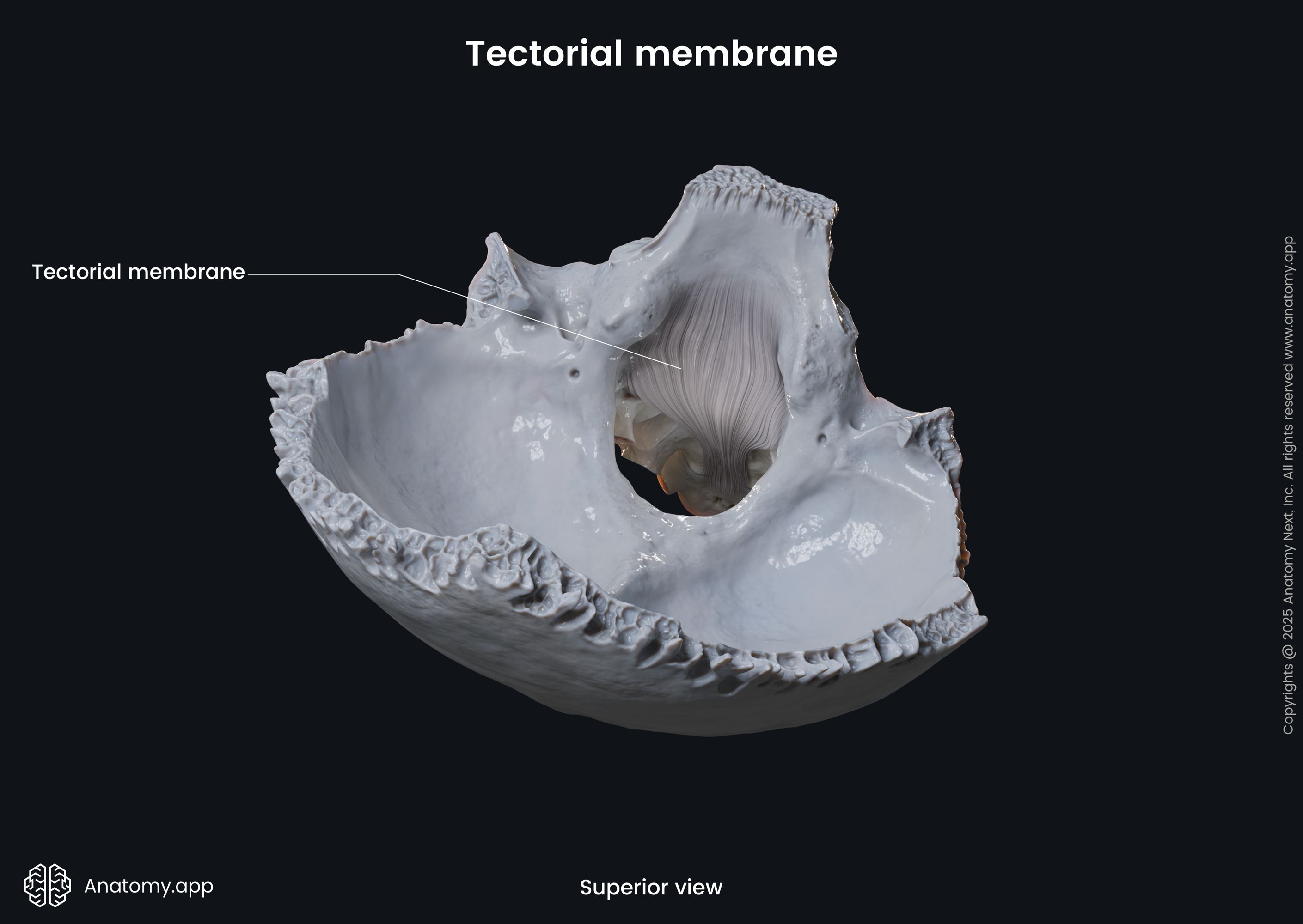

- Tectorial membrane

However, the primary bands that connect the occipital bone with the atlas and thus stabilize the atlanto-occipital joint are the anterior and posterior atlanto-occipital ligaments.

The nuchal ligament is a triangular sheet-like band that stretches between the external occipital protuberance and the tip of the spinous process of the seventh cervical vertebra (C7). It limits flexion of the head and cervical spine, prevents hyperflexion and promotes returning the head to its anatomical position.

The alar ligaments are short and strong fibrous bands that extend between the lateral margins of the upper posterior aspect of the dens of the axis (C2) to the lateral margins of the foramen magnum (medial to the occipital condyles). They limit axial rotation and lateral flexion of the head to the opposite (contralateral) side.

The apical ligament of dens is a weak band that connects the apex of the dens of the axis (C2) to the anterior margin of the foramen magnum. Although some authors state that this ligament probably does not provide any functions, it is considered one of the possible stabilizers of the atlanto-occipital joint.

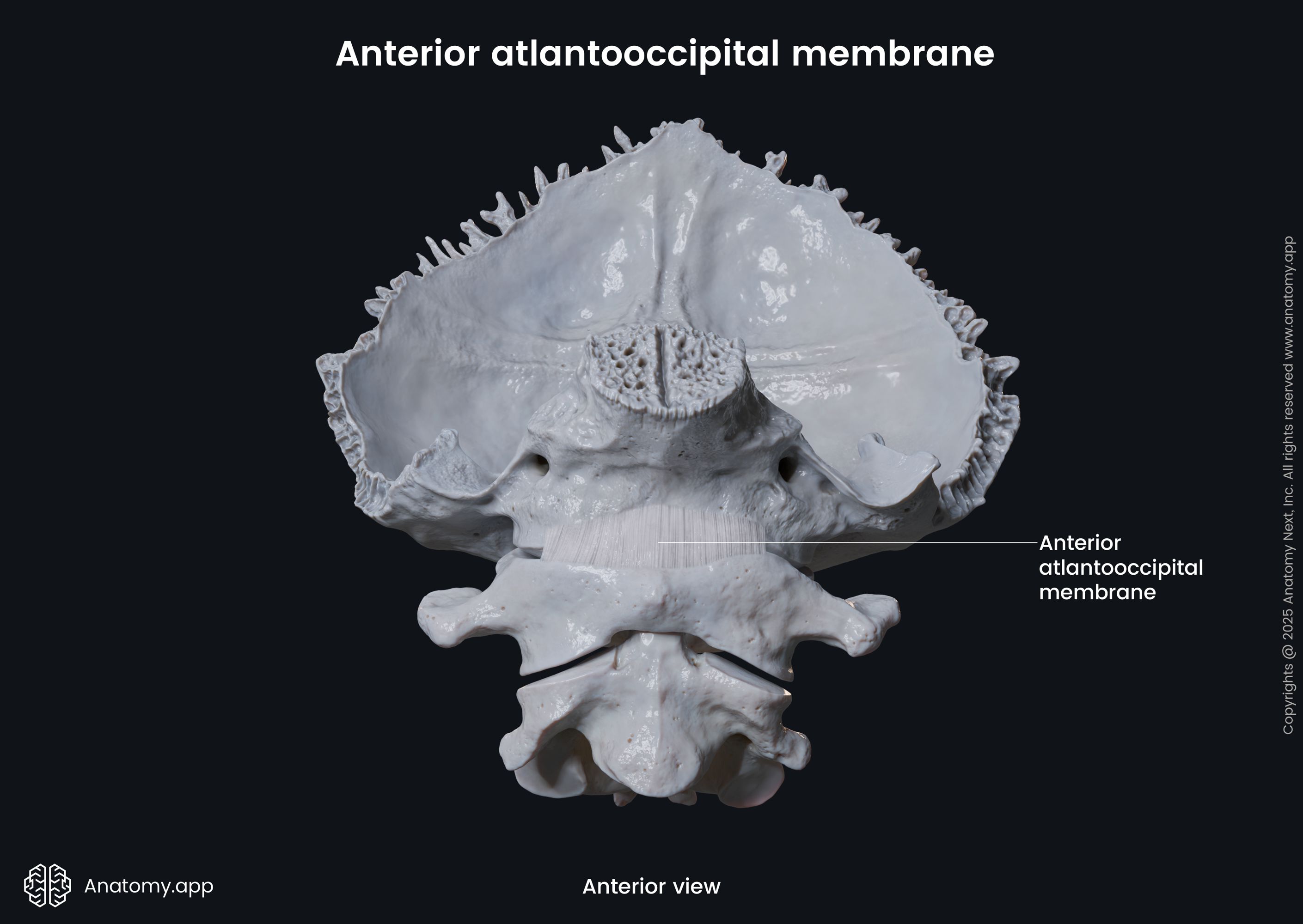

The anterior atlanto-occipital ligament (membrane) is a broad and dense band. It connects the upper aspect of the anterior arch of the atlas to the anterior margin of the foramen magnum. The lateral sides of the ligament merge with the fibrous joint capsules. This ligament prevents excessive neck extension and is a continuation of the anterior longitudinal ligament.

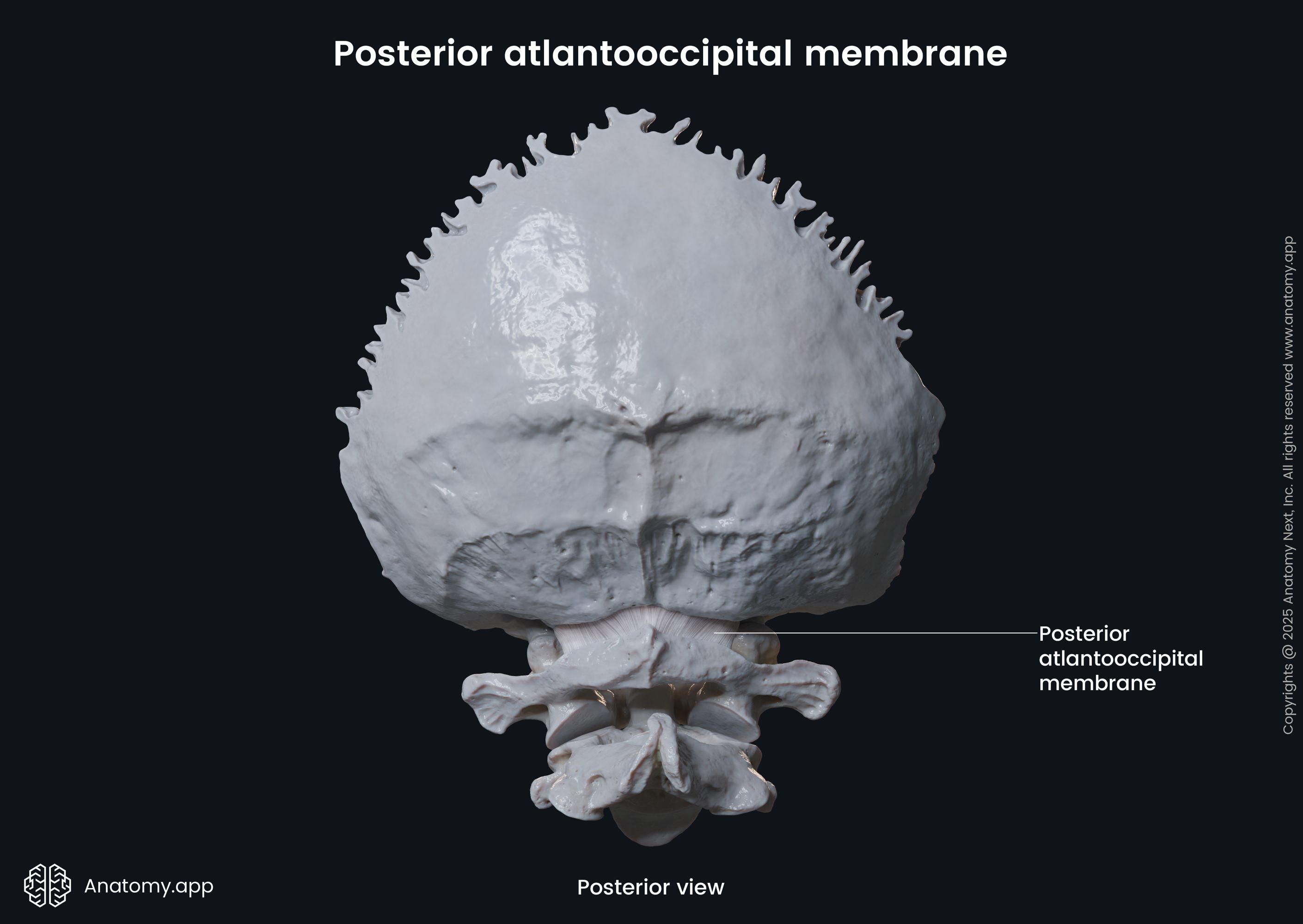

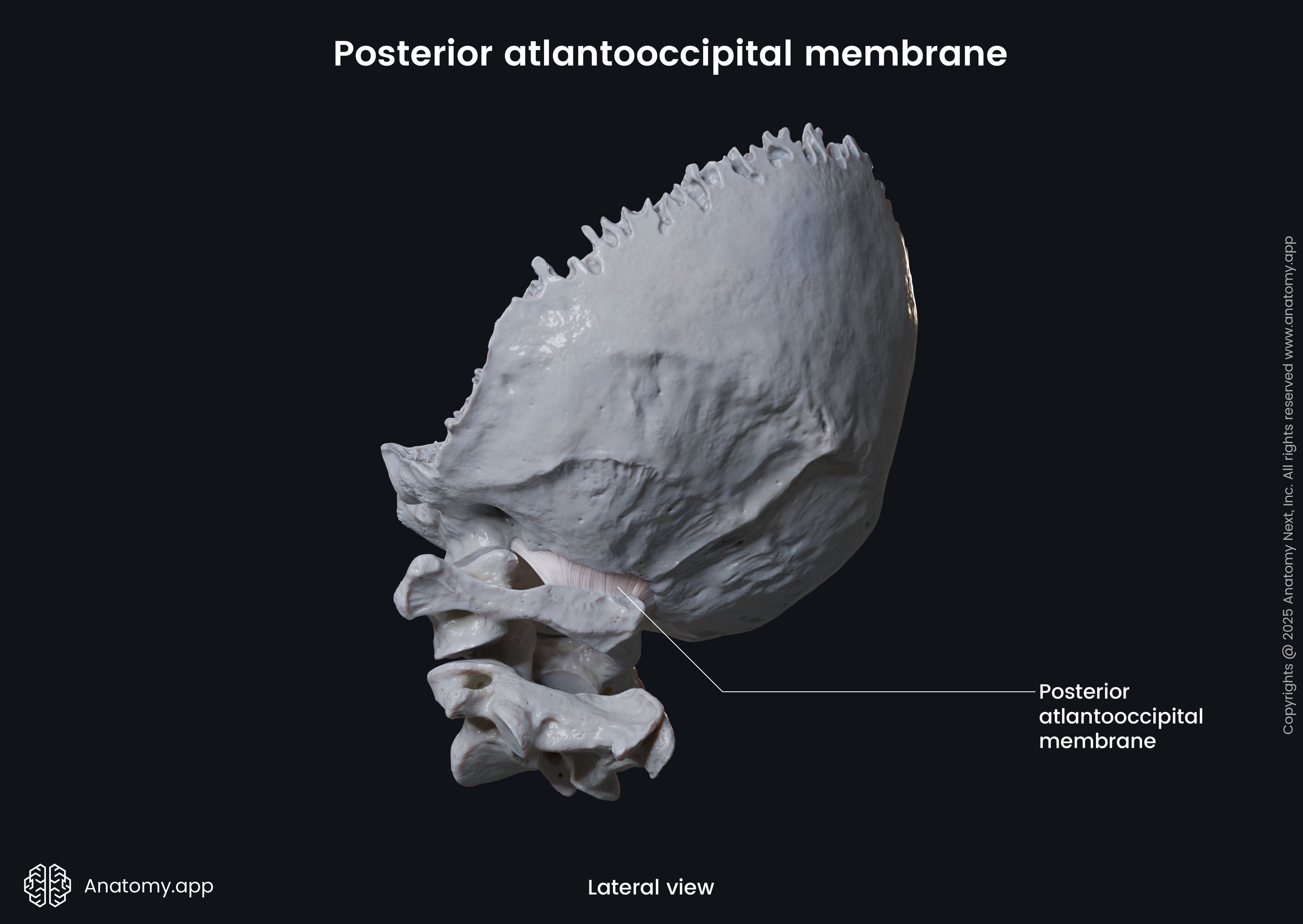

The posterior atlanto-occipital ligament (membrane) is a broad and thin band that connects the superior aspect of the posterior arch of the atlas to the posterior margin of the foramen magnum. Laterally it blends with the fibrous joint capsules. The membrane forms the floor of the suboccipital triangle and covers the vertebral arteries, suboccipital cavernous sinuses (suboccipital venous plexuses) and suboccipital nerves. The posterior atlanto-occipital ligament is a continuation of the yellow ligaments.

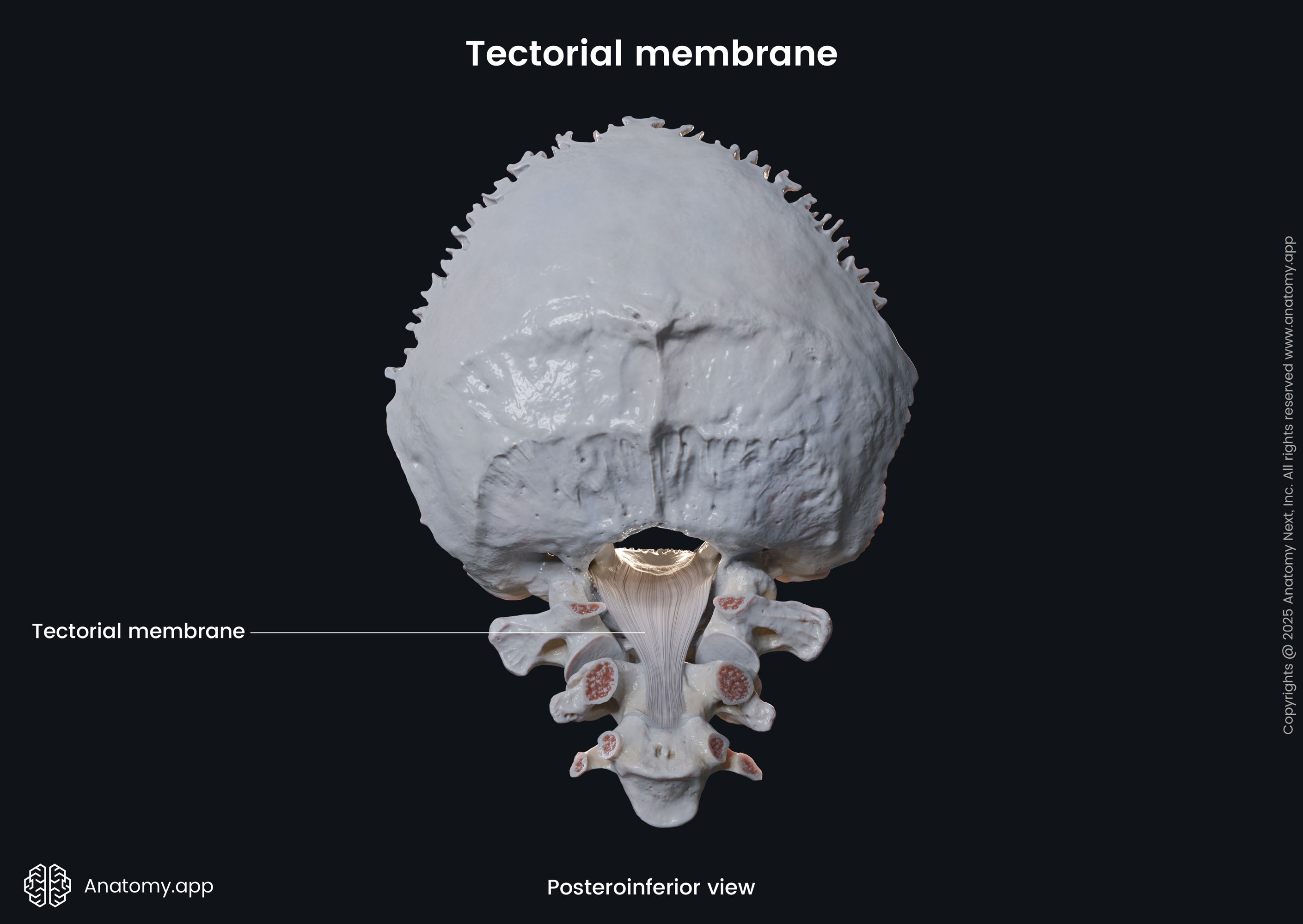

The tectorial membrane is a thin superior extension of the posterior longitudinal ligament. The membrane extends between the clivus of the occipital bone and the posterior aspect of the dens and vertebral body of the axis (C2). It lies posterior to the cruciform ligament of the atlas.

Atlanto-occipital joint movements

The atlanto-occipital joints are biaxial, and they allow movements in two plains. These articulations are responsible for flexion/extension and limited lateral flexion (abduction/adduction), and minimal rotation of the head.

The atlanto-occipital joints primarily enable the head to bend backward (extension) and forward towards the chest (flexion). It is also possible to perform a minimal degree of lateral bending and rotation of the head. However, most cervical rotations happen simultaneously at all joints included in the craniovertebral joint complex.

Muscles providing movements at atlanto-occipital joint

The muscles that enable movements at the atlanto-occipital joint are listed in the table below.

Muscles providing movements at atlanto-occipital joint | |

Flexion | Longus capitis Rectus capitis anterior |

Extension | Rectus capitis posterior minor Rectus capitis posterior major Obliquus capitis superior Semispinalis capitis Longissimus capitis Splenius capitis Sternocleidomastoid Cervical part of the trapezius |

Lateral flexion | Rectus capitis lateralis Semispinalis capitis Splenius capitis Sternocleidomastoid Cervical part of the trapezius |

Rotation | Rectus capitis posterior minor Splenius capitis Sternocleidomastoid |

The flexion of the head at the atlanto-occipital joint happens with the help of longus capitis and rectus capitis anterior muscles.

The extension is provided by the rectus capitis posterior minor, rectus capitis posterior major, obliquus capitis superior, semispinalis capitis, longissimus capitis, splenius capitis, sternocleidomastoid and the cervical part of the trapezius muscle.

Lateral flexion at the atlanto-occipital joint is ensured by the rectus capitis lateralis, semispinalis capitis, splenius capitis, sternocleidomastoid and the cervical part of the trapezius muscle.

And finally, the rectus capitis posterior minor, splenius capitis and sternocleidomastoid muscles enable minimal rotational movements at this joint.

Neurovascular supply

The atlanto-occipital joint receives arterial blood supply from branches of the deep cervical, vertebral and occipital arteries. The venous drainage occurs through the pharyngovertebral veins.

The lymphatic drainage from the atlanto-occipital joint happens through the retropharyngeal lymph nodes. Further, the lymph is carried next to the upper deep cervical lymph nodes.

The innervation of the atlanto-occipital joint is provided by the anterior ramus of the first cervical spinal nerve (C1).

Related structures

The atlanto-occipital joints are surrounded by various anatomical structures. Posterolaterally to the joints lie the vertebral arteries. They pass into the foramen magnum from the transverse foramina. Posteromedially to each joint goes the dorsal ramus of the first cervical spinal nerve (C1), which is also known as the suboccipital nerve. And finally, two muscles also lie next to the atlanto-occipital joint: rectus capitis posterior major (found posteromedially) and rectus capitis anterior (located anteriorly to the joint).

Atlanto-occipital joint issues

Craniovertebral disorders are relatively uncommon and usually have poor outcomes. The abnormalities of the craniovertebral junction can be either congenital or acquired. These issues present as a variety of symptoms such as headaches and neck pain, vertigo, blurred and double vision, tinnitus, voice hoarseness, sleep apnea and difficulty swallowing. The main presentations are usually related to physical compression of the spinal cord, spinal nerves, and/or blood vessels.

Acute, high-energy trauma can lead to atlanto-occipital dissociation (AOD) - a severe ligamentous and/or osseous craniovertebral injury. This type of traumatic separation may result in spino-medullary and/or ponto-medullary laceration and, subsequently, death. It is more common in children, probably because their atlanto-occipital joints are flatter and ligaments are more flexible but weaker. Although AOD is associated with high mortality rates, it is possible to survive this type of craniovertebral injury after surgical repair.

References:

- Browner, B. D. (2021). Skeletal Trauma: Basic Science, Management, and Reconstruction, 2-Volume Set, 5e (Browner, Skeletal Trauma) by Bruce D. Browner MD MHCM FACS (2014–12-23). Saunders; 5 edition (2014–12-23).

- Bruce, F. M., Berkwits, L., Cohen, I., Goodman, B., Kirschner, J., Lee, T. S., & Lin, P. S. (2017). Atlas of Image-Guided Spinal Procedures (2nd ed.). Elsevier.

- Gray, H., & Carter, H. (2021). Gray’s Anatomy (Leatherbound Classics) (Leatherbound Classic Collection) by F.R.S. Henry Gray (2011) Leather Bound (2010th Edition). Barnes & Noble.

- Winn, R. (2022). Youmans and Winn Neurological Surgery: 4 - Volume Set (Youmans Neurological Surgery) (8th ed.). Elsevier.

- Yoganandan, N., Benzel, E.C. (2005) Spine Surgery (Third Edition). Practical Anatomy and Fundamental Biomechanics. Elsevier.