- Anatomical terminology

- Skeletal system

- Joints

- Muscles

- Heart

- Blood vessels

- Lymphatic system

- Nervous system

- Respiratory system

- Digestive system

- Urinary system

- Female reproductive system

- Male reproductive system

- Endocrine glands

- Eye

- Ear

Parathyroid glands

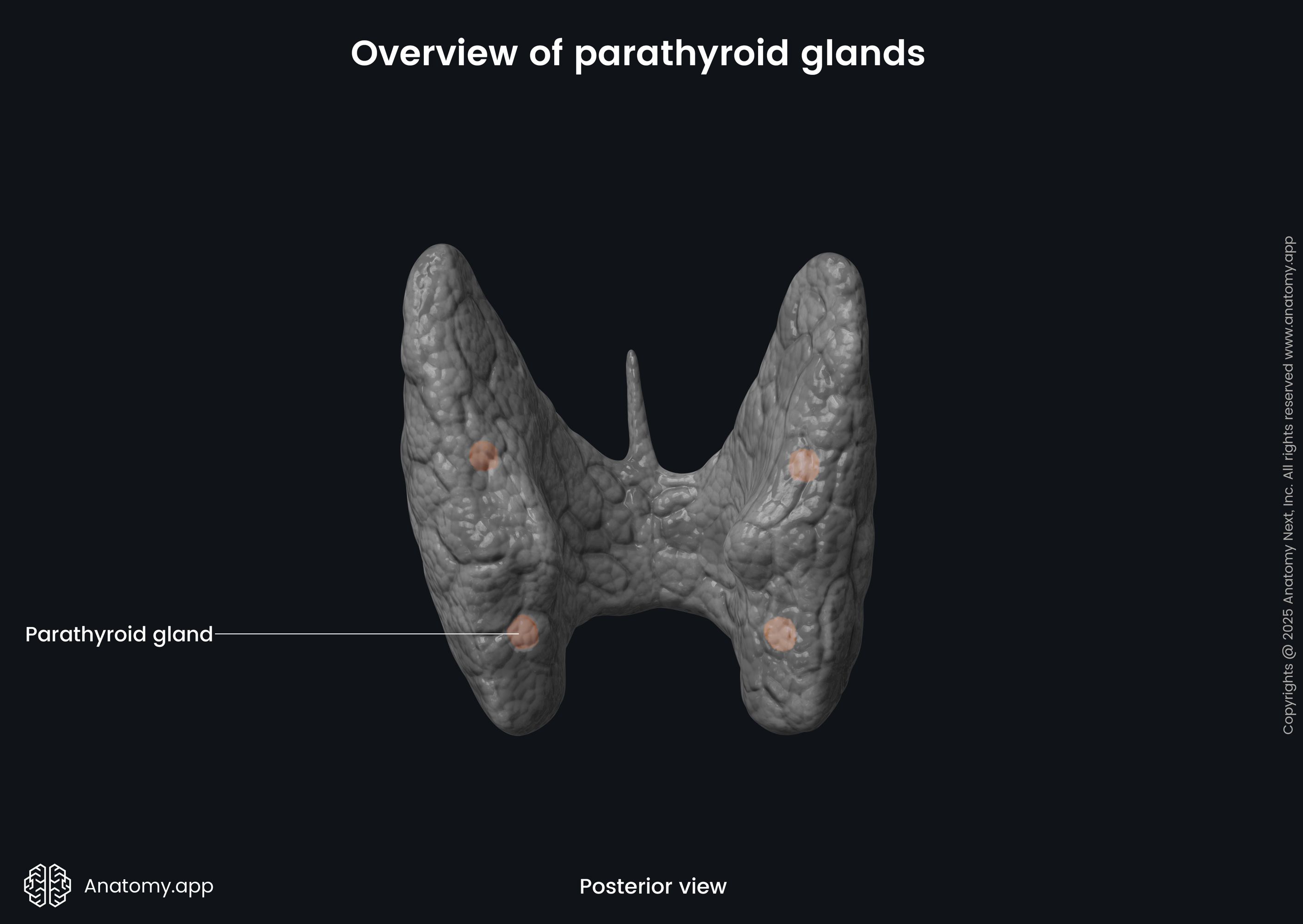

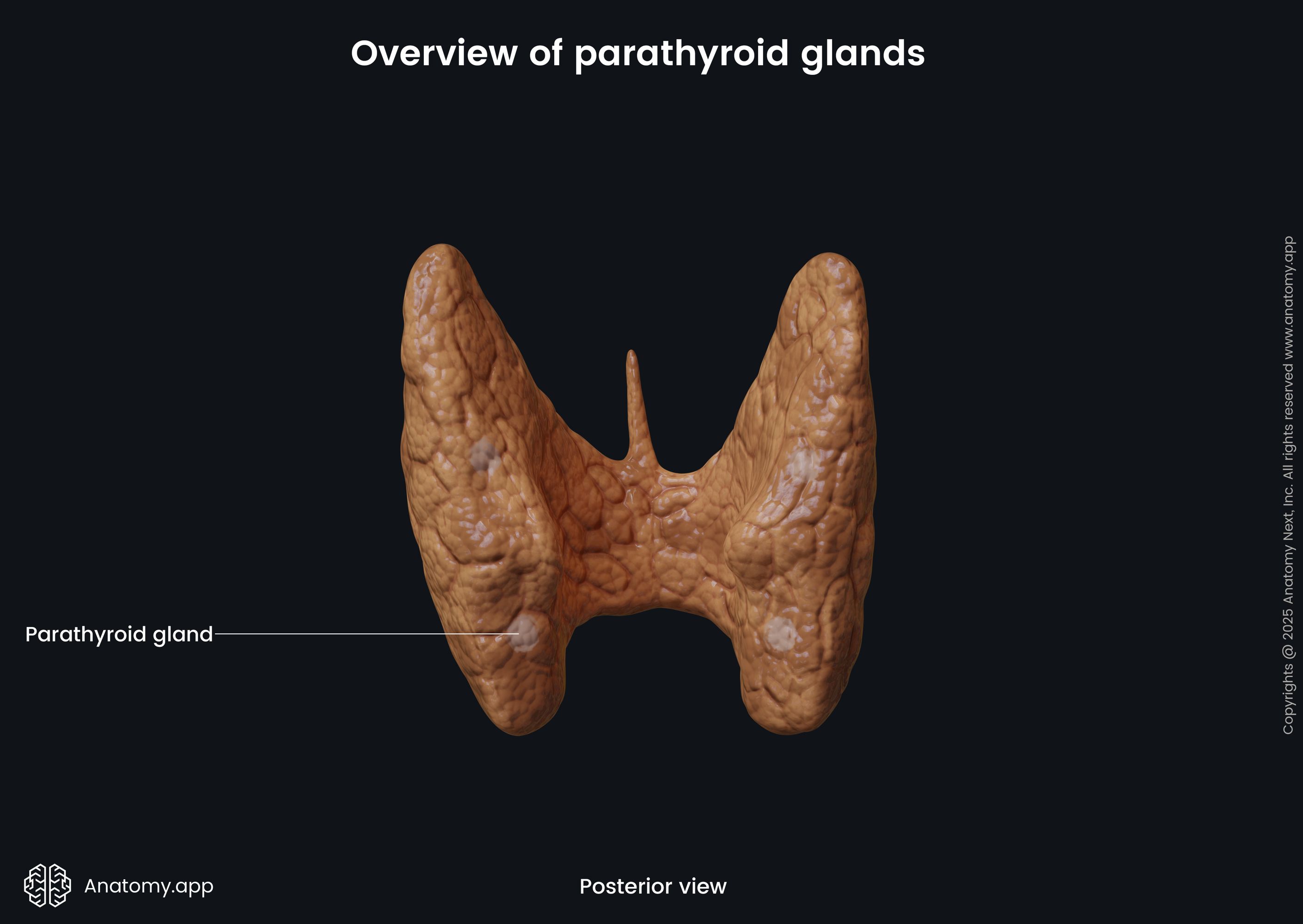

The parathyroid glands (singular in Latin: glandula parathyreoidea) are multiple small endocrine glands located in the neck. There are usually four of them, but the number of these glands may vary. The parathyroid glands are situated on the posterior surface of the thyroid gland, usually, lying on its four poles. They are responsible for parathyroid hormone production (PTH), which happens as a response to the blood calcium levels and are essential in regulating calcium homeostasis.

Parathyroid gland anatomy

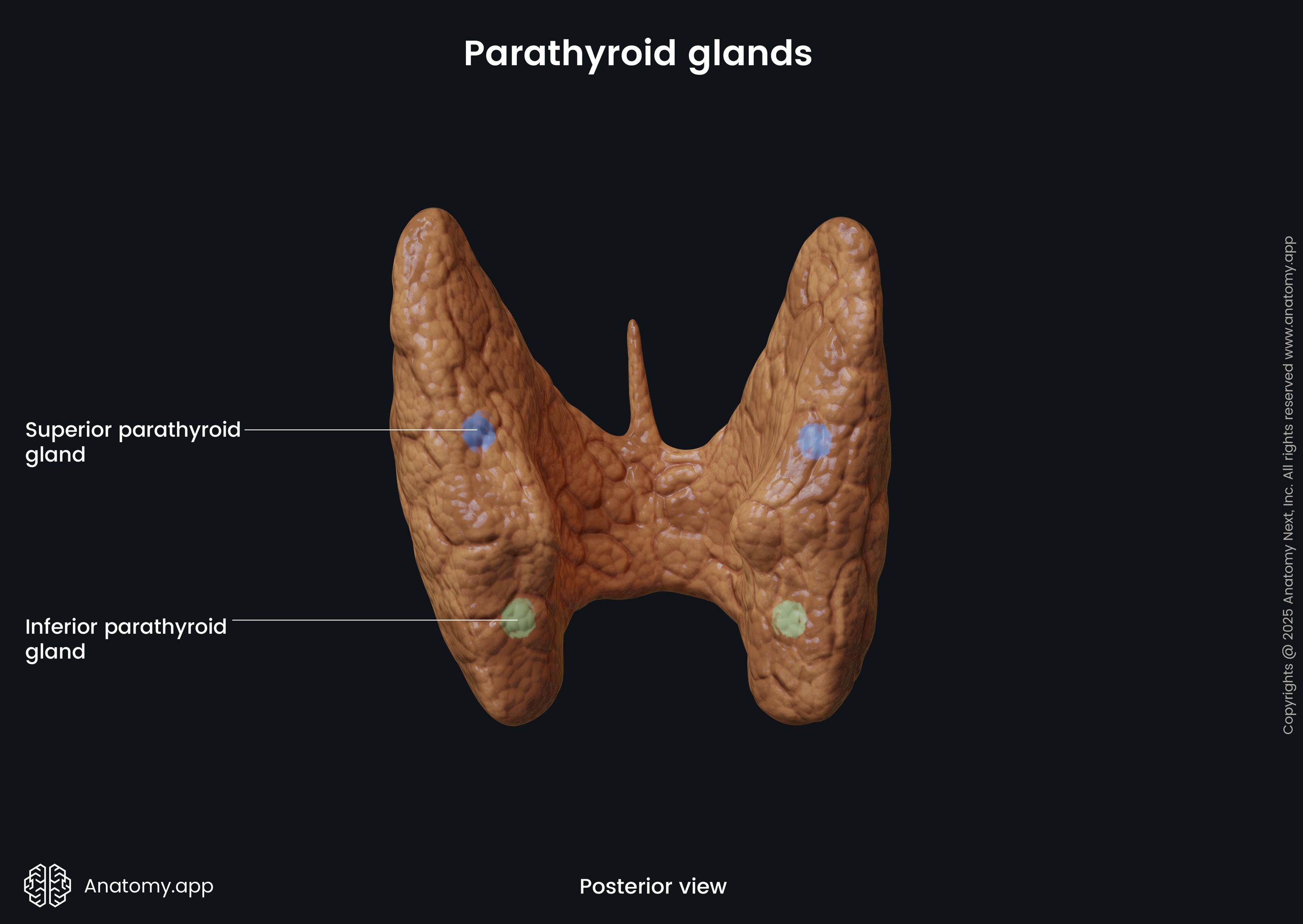

Humans typically have four parathyroid glands, however, some people can have up to six. The glands are small, flattened, oval-shaped. They are located on the posterior surfaces of the right and left lobes of the thyroid glands. The parathyroid glands have a yellowish-brown color.

Each gland is around 6 mm long, 4 mm wide, and 2 mm thick, and weighs around 30-35 g. There are usually two parathyroid glands on each side. The ones that are positioned higher are called the superior parathyroid glands, but the lower ones are called the inferior parathyroid glands.

The location of the superior parathyroid glands is constant. They can be found at the middle of each thyroid lobe's posterior border, at the level of the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage. They are located around 1 cm above the entry of the inferior thyroid artery into the thyroid gland. The superior parathyroid glands are derived from the fourth pharyngeal pouch.

In contrast to the superior glands, the inferior parathyroid glands may have various locations. However, usually, they are located near the inferior poles of the thyroid gland lobes. In some cases, the inferior parathyroid glands can be situated as far down as the superior mediastinum. The inferior parathyroid glands are derived from the third pharyngeal pouch.

Parathyroid gland histology

The parathyroid glands are nodular structures composed of irregular lobes and lobules. The two main cell types within the parathyroid lobes are the chief cells and oxyphil cells. Other cell types found in the parathyroid glands include the clear cells and adipose cells. All these cells are densely packed forming the parenchyma of the parathyroid glands. The stroma is made up from connective tissue that covers the gland in the form of a capsule and extends into the gland as trabeculae, which partially outline the lobes and lobules.

Chief cells

The chief cells are also known as the parathyroid principal cells or just parathyroid cells. They take up the most significant part of the functional parathyroid gland tissue. Despite their considerable number, the chief cells are smaller than the other cells. The chief cells have a polygonal shape with a round nucleus.

In case there is a normal calcium level in the blood, the chief cells are mostly inactive. The dormant chief cells have a smaller number of secretory granules than the active ones. If the calcium level in the blood is low, the chief cells become active as they have calcium-sensing receptor that help them. In response to a low calcium level, the chief cells secrete the parathormone (PTH).

Oxyphil cells

The oxyphil cells are less in number but larger in size compared to the chief cells. The function of these cells is unclear. They appear only during puberty and increase in number with age. Because of their late appearance, it is thought that the oxyphil cells derive from the chief cells. The oxyphil cells have many mitochondria, while the endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, and secretory granules are poorly developed, in contrast to the chief cells.

Parathyroid gland functions

The main function of the parathyroid glands is the hormonal regulation of blood calcium and phosphate levels within a very narrow range. This is important so that the nervous and muscular systems can work properly. The parathyroid glands do this by producing the parathyroid hormone (PTH).

Parathyroid hormone

The parathyroid hormone is secreted by the chief cells of the parathyroid gland. It is a hormone that regulates the blood calcium and phosphate levels by affecting the bones, kidneys, and intestine. PTH secretion is stimulated by the following factors:

- Decreased blood calcium

- Mild decrease in blood magnesium

- Increased blood phosphate

- Adrenaline

- Histamine

And PTH secretion is inhibited by the following::

- Increased blood calcium

- Significantly decreased magnesium level

- Calcitriol

- Decreased blood phosphate

As mentioned before, the PTH is secreted as a response to low calcium level in the blood. The PTH acts on cells within the bones, causing them to release calcium into the bloodstream, thus also regulating the amount of calcium in the bones and therefore affecting bone strength and density.

The hormone stimulates osteoclast activity to release more ionic calcium from the bones into the bloodstream to increase serum calcium levels. Therefore, bones work as a reservoir of calcium to maintain normal calcium levels in the body. PTH indirectly affects osteoclasts by binding to osteoblasts.

Another way that the PTH can raise calcium levels is by acting upon the epithelial cells lining the intestinal tract to increase calcium absorption from the diet. The PTH also affects serum phosphate levels, as it reduces the reabsorption of phosphate from the proximal tubule of the kidney, resulting in increased excretion of phosphate with urine.

The absorption of calcium and phosphate from the intestines is mediated by an increase in activated vitamin D. Calcium absorption is more dependant on vitamin D than phosphate absorption. The PTH also upregulates the enzyme responsible for converting vitamin D to its active form.

Neurovascular supply of parathyroid glands

Arterial blood supply

The arterial supply to the parathyroid glands is similar to that of the thyroid gland. The glands are supplied by branches of the inferior thyroid arteries, which arise from the subclavian arteries. They can also be supplied by anastomoses between the inferior thyroid and superior thyroid arteries, and the thyroid ima artery.

Venous drainage

The parathyroid glands are drained by the superior, middle and inferior thyroid veins. The superior and middle thyroid veins flow into the internal jugular vein, while the inferior thyroid vein drains into the brachiocephalic vein. All three thyroid veins arise from the thyroid venous plexus around the thyroid gland.

Lymphatic drainage

The lymph from the parathyroid glands is collected by lymphatic vessels that drain to the paratracheal and deep cervical lymph nodes.

Innervation

The endocrine secretion of the parathyroid glands is regulated hormonally, while the blood vessels of the gland receive rich innervation from the sympathetic nervous system via branches of the sympathetic trunk. Namely, they are supplied by branches arising from the thyroid branches of the cervical ganglia. These nerves are vasomotor, not secretomotor.

Parathyroid gland disorders

The parathyroid gland disorders may be divided into two groups based on the activity of the parathyroid glands. If the parathyroid glands are overactive, it is known as hyperparathyroidism. On the other hand, if the parathyroid glands are underactive, it is known as hypoparathyroidism.

Hyperparathyroidism

In case of hyperparathyroidism there is an increase in blood PTH because the parathyroid glands are overactive. This increases the blood calcium levels, leading to hypercalcemia. Hyperparathyroidism can be primary, secondary or tertiary. Primary hyperparathyroidism is caused by a tumor in the parathyroid gland. It can be parathyroid adenoma, parathyroid hyperplasia, or parathyroid carcinoma. Surgery to remove the parathyroid gland usually is the first choice of treatment. The symptoms of primary hyperparathyroidism are connected to hypercalcemia, and they may include the following:

- Kidney stones

- Constipation, indigestion

- Nausea, vomiting

- Osteoporosis, osteomalacia

- Lethargy, fatigue

- Depression

- Memory loss

- Psychosis, delirium

Secondary hyperparathyroidism usually occurs as a response to long-term hypocalcemia. The most common cause of hypocalcemia is chronic kidney failure. In rarer cases, the reason may be malabsorption. Most of the symptoms in the case of secondary hyperparathyroidism are connected to the underlying disease. People can also experience bone and joint pain, limb deformities. The treatment usually starts by treating the underlying cause.

Tertiary hyperparathyroidism occurs after prolonged secondary hyperparathyroidism when the parathyroid glands do not respond to the serum calcium levels. Symptoms usually are the same as in case of primary hyperparathyroidism and hypercalcemia. Treatment is based on the underlying cause.

Hypoparathyroidism

Hypoparathyroidism occurs when the parathyroid glands are not working properly and secretion of PTH is decreased, which results in low serum calcium levels (hypocalcemia). Hypoparathyroidism can be caused by removal of the parathyroid glands during surgery, autoimmune diseases, magnesium deficiency, and hemochromatosis. Signs and symptoms of hypoparathyroidism include the following symptoms of hypocalcemia:

- Paresthesia

- Fatigue, headaches

- Bone pains

- Insomnia

- Abdominal cramps

- Chvostek's sign (twitching of the facial muscles by stimulating the facial nerve)

- Trousseau's sign (hyperreflexia and tetany after obstructing blood flow to the arm by using a blood pressure cuff)

Treatment of hypoparathyroidism starts with intravenous calcium administration as severe hypocalcemia can be life-threatening. Vitamin D is prescribed as a long-term treatment.